Structural Transformations in Tribal Societies, 1999-2011: Evidence from ‘least developed’ states – Archana Prasad

Of the five states described as ‘least developed’ by the Report of the Raghuram Rajan Committee on

Evolving a Composite Developmental Index four have a considerably large

scheduled tribe population. It is also significant that all these states boast

a robust annual growth rate and have pursued aggressive policies which have

resulted in the changing class differentiation within tribal people. This

differentiation is also a result of the forms of adverse integration of tribal

workers into rural and urban labour markets. The increasing labour mobility

amongst the scheduled tribe population is reflected in the growing trends of

urbanisation and changing intensity of dispossession amongst tribal people.

Evolving a Composite Developmental Index four have a considerably large

scheduled tribe population. It is also significant that all these states boast

a robust annual growth rate and have pursued aggressive policies which have

resulted in the changing class differentiation within tribal people. This

differentiation is also a result of the forms of adverse integration of tribal

workers into rural and urban labour markets. The increasing labour mobility

amongst the scheduled tribe population is reflected in the growing trends of

urbanisation and changing intensity of dispossession amongst tribal people.

The

root cause of these changing patterns of mobility and rising inequities within

tribal communities is the continuing structural changes in the agrarian

economy, both interms of the consolidation of land holdings and the penetration

of big capital into export led commercial agriculture. This is particularly

true of states like Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh where contract and

corporate farming in tribal lands has been a result of sustained policy

initiatives that are consistently linking tribal farmers and rural farmers to

national and global markets. Third party industry agreements in joint forest

management projects (in states like Andhra) and the promotion of export and

industry oriented agricultural produce like safed musli (for example in Bastar,

Chhattigarh), soya bean (through the ITC in Madhya Pradesh) and floriculture in

large parts of Chhattisgarh has fundamentally changed the agrarian relations

within the tribal regions. This article shows that it has also led to growing

inequities within the tribal society as revealed in the available sources of

data for the scheduled tribes.

root cause of these changing patterns of mobility and rising inequities within

tribal communities is the continuing structural changes in the agrarian

economy, both interms of the consolidation of land holdings and the penetration

of big capital into export led commercial agriculture. This is particularly

true of states like Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh where contract and

corporate farming in tribal lands has been a result of sustained policy

initiatives that are consistently linking tribal farmers and rural farmers to

national and global markets. Third party industry agreements in joint forest

management projects (in states like Andhra) and the promotion of export and

industry oriented agricultural produce like safed musli (for example in Bastar,

Chhattigarh), soya bean (through the ITC in Madhya Pradesh) and floriculture in

large parts of Chhattisgarh has fundamentally changed the agrarian relations

within the tribal regions. This article shows that it has also led to growing

inequities within the tribal society as revealed in the available sources of

data for the scheduled tribes.

FORMS OF LAND DISPOSSESSION IN TRIBAL INDIA

Ownership and control of land, particularly cultivated land is one of

the basic characteristics of the growing inequities within tribal societies.

The decadal changes in the land ownership patterns of four least developed

states with tribal population reveal a growing landlessness amongst tribal

people in these states in three different periods between 1999-2000 and 2010-11

(a decade that is temporally comparable with the census data enumeration in

2001 and 2011)

the basic characteristics of the growing inequities within tribal societies.

The decadal changes in the land ownership patterns of four least developed

states with tribal population reveal a growing landlessness amongst tribal

people in these states in three different periods between 1999-2000 and 2010-11

(a decade that is temporally comparable with the census data enumeration in

2001 and 2011)

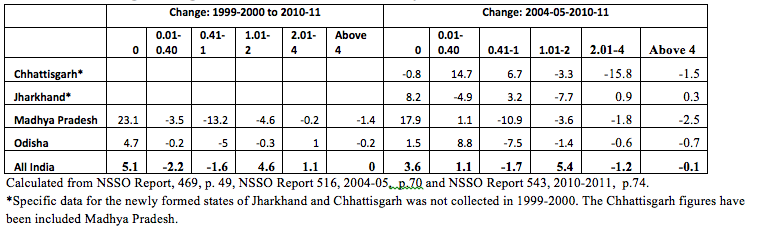

Table:1 Percentage Changes Access

to Cultivated Land by Scheduled Tribes, 1999-2010

This table shows that the decedal increase in landlessness amongst the

scheduled tribes has been the highest in Madhya Pradesh in the period between

2000-2011. While the increase in landlessness is lower than the all India

average in all states except Jharkhand percentage of marginal holdings below 1

hectare has registered a significant rise in all the four states. This clearly

indicates that medium size land holdings are getting fragmented but the loss of

land amongst the adivasis may not be absolute in its character. This means that

those with larger land holdings are loosing a significant part of their land

but not all their land so as to be classed as ‘landless’.

Chhattisgarh is

especially significant in this regard since there seems to be an unusual

increase in medium adivasi land holders, a phenomena that has possibly arisen

out of the Chhattisgarh governments contract farming initiative where adivasi

peasants are directly linked to corporate houses. This rise in marginal and

medium land holdings at the same time indicates a fundamental change within the

class structure of the Chhattisgarh adivasis and can explain the spurt in urban

growth rates of adivasis in the state. The secular rise in marginal land

holdings has to be seen as a part of the larger proletarianisation of the tribal

people. It is even more interesting to note that the rate of decline of large

and medium land holdings within scheduled tribes is considerably less than that

of small and marginal holdings. At an all India level, the picture emerges in a

more complex form. The rate of decline of large land holdings is much slower

than marginal and sub-marginal holdings. This indicates that the tribal people

with larger land holdings are able to retain their ownership where as the marginal

farmers were becoming dispossessed, increasing the inequities between the

landholders and the landless tribal workers.

scheduled tribes has been the highest in Madhya Pradesh in the period between

2000-2011. While the increase in landlessness is lower than the all India

average in all states except Jharkhand percentage of marginal holdings below 1

hectare has registered a significant rise in all the four states. This clearly

indicates that medium size land holdings are getting fragmented but the loss of

land amongst the adivasis may not be absolute in its character. This means that

those with larger land holdings are loosing a significant part of their land

but not all their land so as to be classed as ‘landless’.

Chhattisgarh is

especially significant in this regard since there seems to be an unusual

increase in medium adivasi land holders, a phenomena that has possibly arisen

out of the Chhattisgarh governments contract farming initiative where adivasi

peasants are directly linked to corporate houses. This rise in marginal and

medium land holdings at the same time indicates a fundamental change within the

class structure of the Chhattisgarh adivasis and can explain the spurt in urban

growth rates of adivasis in the state. The secular rise in marginal land

holdings has to be seen as a part of the larger proletarianisation of the tribal

people. It is even more interesting to note that the rate of decline of large

and medium land holdings within scheduled tribes is considerably less than that

of small and marginal holdings. At an all India level, the picture emerges in a

more complex form. The rate of decline of large land holdings is much slower

than marginal and sub-marginal holdings. This indicates that the tribal people

with larger land holdings are able to retain their ownership where as the marginal

farmers were becoming dispossessed, increasing the inequities between the

landholders and the landless tribal workers.

The importance of the enactment and implementation of the forest rights

act has to be considered in this context and perspective. At the time of its

enactment the advocates of tribal rights anticipated that this Act could be an

antidote to both displacement and dispossession. But its implementation, when

compared with the diversion of forest lands for other projects, serves as a

grim reminder of the reality. According to the CAG Report on the Implementation

of the Compensatory Afforestation scheme in India, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand,

Madhya Pradesh and Odisha account for about 51 per cent of the diversion of

forest lands for corporate projects. If Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh and

Rajasthan are added to this list than these seven states account for about 70

per cent of the land diverted for non-forestry purposes. However this fact is

also accompanied by the lack or recognition of land rights under the Forest

Rights Act. The scenario for the ‘least developed states’ is the following:

act has to be considered in this context and perspective. At the time of its

enactment the advocates of tribal rights anticipated that this Act could be an

antidote to both displacement and dispossession. But its implementation, when

compared with the diversion of forest lands for other projects, serves as a

grim reminder of the reality. According to the CAG Report on the Implementation

of the Compensatory Afforestation scheme in India, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand,

Madhya Pradesh and Odisha account for about 51 per cent of the diversion of

forest lands for corporate projects. If Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh and

Rajasthan are added to this list than these seven states account for about 70

per cent of the land diverted for non-forestry purposes. However this fact is

also accompanied by the lack or recognition of land rights under the Forest

Rights Act. The scenario for the ‘least developed states’ is the following:

Table

2: Diversion of Forest

Lands (2010-13) and Implementation of Forest Rights Act,2013

Of the four least developed states, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh and Madhya

Pradesh have a poor record in the settlement of claims under the Forest Rights

Act. Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh also have the highest rate of diversion of

forest lands for non-forestry purposes. Most of this diversion is for the

purposes of private mining projects which have a big impact in the displacement

of tribal livelihoods. This is clearly seen in the decedal changes in land

ownership as shown previously.

In fact, in Madhya Pradesh landlessness has

increased by 23.1 percent in the decade of 2000-2011, and in Chhattisgarh by

8.2 percent between 2005 and 2011. This clearly indicates that the class

position of the adivasi as a rural worker rather than as a peasant has been

further reinforced ever since the post-economic reform period. But today, most

adivasis are unable to find gainful employment opportunities in agriculture. Such

a conclusion is only reinforced by the Census data of 2011.

Pradesh have a poor record in the settlement of claims under the Forest Rights

Act. Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh also have the highest rate of diversion of

forest lands for non-forestry purposes. Most of this diversion is for the

purposes of private mining projects which have a big impact in the displacement

of tribal livelihoods. This is clearly seen in the decedal changes in land

ownership as shown previously.

In fact, in Madhya Pradesh landlessness has

increased by 23.1 percent in the decade of 2000-2011, and in Chhattisgarh by

8.2 percent between 2005 and 2011. This clearly indicates that the class

position of the adivasi as a rural worker rather than as a peasant has been

further reinforced ever since the post-economic reform period. But today, most

adivasis are unable to find gainful employment opportunities in agriculture. Such

a conclusion is only reinforced by the Census data of 2011.

Transforming Occupational Structures Amongst

Tribals

The long term impact of the forms and patterns of dispossession are

reflected in the Census of India, 2011. The following picture emerges when

compared with the Census of India, 2001:

reflected in the Census of India, 2011. The following picture emerges when

compared with the Census of India, 2001:

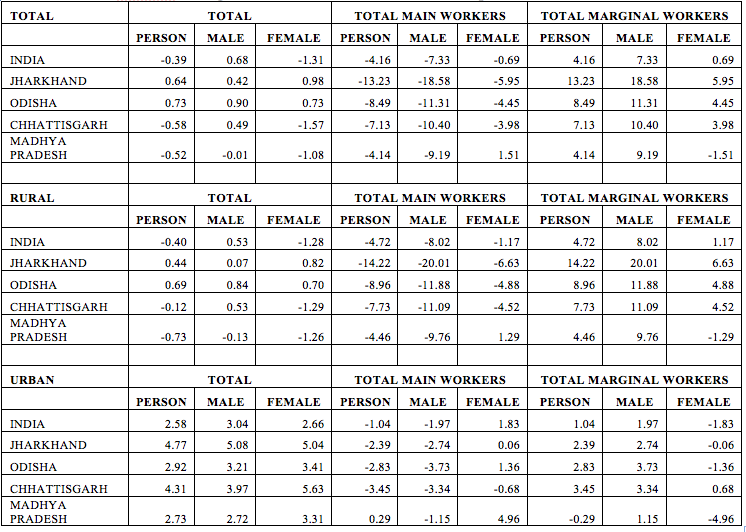

Table 3: Decedal Changes in Scheduled

Tribe Work Participation Rates, 2001-2011

Data Computed from Census of India, 2001 ST01 and ST02; Census of

Data Computed from Census of India, 2001 ST01 and ST02; Census ofIndia, 2011, ST Tables Online data.

The table above shows a secular decline in the number of main workers or

workers getting more than 180 day of regular work in one year, even though

there is only a marginal decline or increase in the total work participation

rates. What is more interesting to note is the fact that this decline is more

drastic in the rural regions of all regions except Madhya Pradesh whose decline

in the main rural workforce is lower than that of the all India workforce. This

figure becomes especially significant when we consider the fact that the main

work participation rate of women has increased in the state. This is in stark

contrast to the decline in the work participation rates of the marginal female

workforce in the state in the same period. But overall the secular increase in

marginal tribal rural workforce (that people working for less than six months a

year) is reflective of the larger rural crisis that has fundamentally impacted

tribal livelihoods. In contrast there is a generalised increase in the main

female urban workforce in all cases except for Chhattisgarh, and the decline in

the urban male workforce in the same period highlights the gendered nature of

the changes in the occupational structure. Further even though there is a

general all India increase in the total work participation rate for scheduled

tribes it is largely a result of the increasing rates of marginal rural and

urban work. But even here, the rate of increase in total and rural female

marginal work is higher than that of males.

Significantly the decline in female

marginal workers in the urban areas is replaced by a corresponding increase in

the main female urban workers. Once again this indicates that schedule tribe

women are shouldering greater responsibility to meet the daily needs of urban

survival.

workers getting more than 180 day of regular work in one year, even though

there is only a marginal decline or increase in the total work participation

rates. What is more interesting to note is the fact that this decline is more

drastic in the rural regions of all regions except Madhya Pradesh whose decline

in the main rural workforce is lower than that of the all India workforce. This

figure becomes especially significant when we consider the fact that the main

work participation rate of women has increased in the state. This is in stark

contrast to the decline in the work participation rates of the marginal female

workforce in the state in the same period. But overall the secular increase in

marginal tribal rural workforce (that people working for less than six months a

year) is reflective of the larger rural crisis that has fundamentally impacted

tribal livelihoods. In contrast there is a generalised increase in the main

female urban workforce in all cases except for Chhattisgarh, and the decline in

the urban male workforce in the same period highlights the gendered nature of

the changes in the occupational structure. Further even though there is a

general all India increase in the total work participation rate for scheduled

tribes it is largely a result of the increasing rates of marginal rural and

urban work. But even here, the rate of increase in total and rural female

marginal work is higher than that of males.

Significantly the decline in female

marginal workers in the urban areas is replaced by a corresponding increase in

the main female urban workers. Once again this indicates that schedule tribe

women are shouldering greater responsibility to meet the daily needs of urban

survival.

In this context a further probe into the nature of occupational changes

reveals a rather interesting scenario of working class formation and

consolidation amongst the scheduled tribes. The decedal changes in the

industrial classification of main workers reflect the land dispossession that

is taking place amongst the tribals.

reveals a rather interesting scenario of working class formation and

consolidation amongst the scheduled tribes. The decedal changes in the

industrial classification of main workers reflect the land dispossession that

is taking place amongst the tribals.

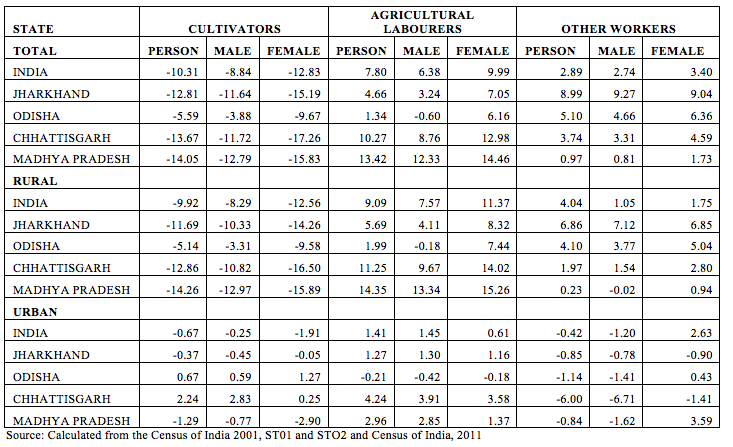

Given the figures for increasing landlessness amongst the tribal people,

it is not surprising that the number of tribal cultivators or peasants have

declined by more than 10 percent in all least developed states except for

Odisha where the rate of decline is less than the all India average of 10.31

percent. As expected most of this decline is amongst the tribal farmers of

rural areas, but this decrease is also gendered in its character. The rate of decline

in female cultivators is higher than that of male cultivators in the rural

regions indicating that female farmers and female headed households face a

greater degree of vulnerability. An interesting aspect of changes in work

patterns relate to the category of ‘other workers’. Here to the rate of increase in female work

participation rate is higher than that of males.

Significantly that though

there is a secular decline in the category of “other workers” in urban areas,

the female urban work participation rates in this period seem to be increasing

at an all India level and at least in two of the four least developed states.

In states like Odisha the rate of its decline is small and much lower than the

rate of decline of male work participation. This leads us to the conclusion that more

women are being forced into the non-agricultural workforce as far as regular

work is concerned.

it is not surprising that the number of tribal cultivators or peasants have

declined by more than 10 percent in all least developed states except for

Odisha where the rate of decline is less than the all India average of 10.31

percent. As expected most of this decline is amongst the tribal farmers of

rural areas, but this decrease is also gendered in its character. The rate of decline

in female cultivators is higher than that of male cultivators in the rural

regions indicating that female farmers and female headed households face a

greater degree of vulnerability. An interesting aspect of changes in work

patterns relate to the category of ‘other workers’. Here to the rate of increase in female work

participation rate is higher than that of males.

Significantly that though

there is a secular decline in the category of “other workers” in urban areas,

the female urban work participation rates in this period seem to be increasing

at an all India level and at least in two of the four least developed states.

In states like Odisha the rate of its decline is small and much lower than the

rate of decline of male work participation. This leads us to the conclusion that more

women are being forced into the non-agricultural workforce as far as regular

work is concerned.

This picture contrasts with the decedal changes in the character of

marginal work. The data shows that though the number of tribal marginal other

workers have gone up in both urban and rural areas (Table 3) the increase is

much higher in the case of male worker participation rates (7.33 percent) as

compared with female marginal work participation rates (0.69 percent). The

pattern of this trend is more evident in the rural areas where work

participation rates of marginal work have increased by 4.02 percent overall and

for male workers they have risen by 8.2 percent in rural and 1.97 percent in

urban areas. In the four states under consideration the rural marginal work for

male workers has risen by almost 20 percent in Jharkhand and more than 10

percent in Odisha and Chhattisgarh. In Madhya Pradesh it has risen close to 10

percent, a figure higher than the all India average. Almost all this increase

is in category of ‘other workers’ in the case of Odisha and Jharkhand and

agricultural labour in the case of Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh.

marginal work. The data shows that though the number of tribal marginal other

workers have gone up in both urban and rural areas (Table 3) the increase is

much higher in the case of male worker participation rates (7.33 percent) as

compared with female marginal work participation rates (0.69 percent). The

pattern of this trend is more evident in the rural areas where work

participation rates of marginal work have increased by 4.02 percent overall and

for male workers they have risen by 8.2 percent in rural and 1.97 percent in

urban areas. In the four states under consideration the rural marginal work for

male workers has risen by almost 20 percent in Jharkhand and more than 10

percent in Odisha and Chhattisgarh. In Madhya Pradesh it has risen close to 10

percent, a figure higher than the all India average. Almost all this increase

is in category of ‘other workers’ in the case of Odisha and Jharkhand and

agricultural labour in the case of Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh.

The facts presented above reveals the different methods of the

integration of the ‘tribal worker’ into labour markets and the economy at large.

In the case of states like Odisha and Jharkhand the sharp rise in the male and

female rural ‘other workers’ is more a result of private mining and

construction works in legally demarcated rural areas. But the changing economic

geography of these regions indicates the development of a peri-urban workforce

especially with the setting up of industrial townships with the help of private

corporate capital. In case of Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh the consolidation

of land holdings under the control of relatively large farmers is inspired by a

governmental push towards contract farming and export led agriculture through

corporate support. Further the data also supports the argument that the rate of

increase of the entry of female tribal workers into the regular labour market

is higher than that of the tribal male workers in most cases. This clearly

shows that the work patterns within the scheduled tribes are emerging largely in

contrast to the general decline in the female workforce participation within

the Indian labour market.

In all cases however, it is clear that the status of

the scheduled tribe is getting consolidated as a rural and urban worker and not

as a farmer. In this situation the slow implementation of the Unorganised

Sector Workers Social Security Act, 2008 and Forest Rights Act, 2006 will only

further hurt the interests of the scheduled tribes in contemporary India.

integration of the ‘tribal worker’ into labour markets and the economy at large.

In the case of states like Odisha and Jharkhand the sharp rise in the male and

female rural ‘other workers’ is more a result of private mining and

construction works in legally demarcated rural areas. But the changing economic

geography of these regions indicates the development of a peri-urban workforce

especially with the setting up of industrial townships with the help of private

corporate capital. In case of Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh the consolidation

of land holdings under the control of relatively large farmers is inspired by a

governmental push towards contract farming and export led agriculture through

corporate support. Further the data also supports the argument that the rate of

increase of the entry of female tribal workers into the regular labour market

is higher than that of the tribal male workers in most cases. This clearly

shows that the work patterns within the scheduled tribes are emerging largely in

contrast to the general decline in the female workforce participation within

the Indian labour market.

In all cases however, it is clear that the status of

the scheduled tribe is getting consolidated as a rural and urban worker and not

as a farmer. In this situation the slow implementation of the Unorganised

Sector Workers Social Security Act, 2008 and Forest Rights Act, 2006 will only

further hurt the interests of the scheduled tribes in contemporary India.

Archana Prasad is Professor at Centre for Informal Sector and Labour

Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi