Dr. Nilanjana Paul

The release of the movie Padmavati,

The release of the movie Padmavati,directed by Sanjay Leela Bhansali, is the center of current debate between the Mumbai

film fraternity and Karni Sena of Rajasthan. Lokendra Singh Kalvi, founder of

the Shri Rajput Karni Sena called for Bharat Bandh

(All India Shutdown) if the movie is released on December 1. In the wake of the

threats, the release of the film has been postponed indefinitely by the

producers. Karni Sena,is a caste based Hindu organization, that claims to defend

the rights of Rajputs (patrilineal

clans associated with warriorhood). Karni Sena has a long history of opposing

movies such as the Jodha Akbar and

destroying the sets of Padmavati.

They claimed that the intimate scene between Rani Padmavati and Alauddin Khilji

went against the values and sentiments of the Rajput community. Since then a

lot has been written on Padmavati and

how it should be open to historical interpretation.This article aims to

problematize how both the movie and the opposition faced by it are part of the

larger Hindutva project to divide the country based on religion in an already

polarized situation.

Padmavat: The Plot

Professor

Irfan Habib argues that Rani Padmavati was a fictional character and there is no

reference to her before 1540. Ramya Srinivasanin her book Many Lives of a Rajput Queen has shown that Sufi Muhammad Jayasi’s Padmavat was composed in 1540 in Awadhi.

In the story, Padmavati was the daughter of Gandharvasen, the ruler of Singhal

(Ceylon or present-day Sri Lanka). She had a parrot called Hiraman. Padmavati

and Hiraman became friends but the king resented the friendship. He wanted to

kill the parrot. However, the parrot managed to escape the palace and was later

taken to Chittor (kingdom in Rajasthan) by a Brahmin. The King of Chittor,

Ratansen, heard about Padmavati’s beauty from the parrot and wanted to marry

her.

Irfan Habib argues that Rani Padmavati was a fictional character and there is no

reference to her before 1540. Ramya Srinivasanin her book Many Lives of a Rajput Queen has shown that Sufi Muhammad Jayasi’s Padmavat was composed in 1540 in Awadhi.

In the story, Padmavati was the daughter of Gandharvasen, the ruler of Singhal

(Ceylon or present-day Sri Lanka). She had a parrot called Hiraman. Padmavati

and Hiraman became friends but the king resented the friendship. He wanted to

kill the parrot. However, the parrot managed to escape the palace and was later

taken to Chittor (kingdom in Rajasthan) by a Brahmin. The King of Chittor,

Ratansen, heard about Padmavati’s beauty from the parrot and wanted to marry

her.

Ratansen

was successful in his quest of marrying Padmavati and brought her to Chittor. A

Brahmin scholar expelled from the court of Chittor took the story to

Alauddin Khilji who then attacked kingdom. However, Ratansen had died fighting

another Rajput ruler even before the arrival of Alauddin. In this grief Padmavati

had immolated herself on the husband’s pyre. Jayasi points out that Alauddin

had lost the battle even though Chittor became Islam.

was successful in his quest of marrying Padmavati and brought her to Chittor. A

Brahmin scholar expelled from the court of Chittor took the story to

Alauddin Khilji who then attacked kingdom. However, Ratansen had died fighting

another Rajput ruler even before the arrival of Alauddin. In this grief Padmavati

had immolated herself on the husband’s pyre. Jayasi points out that Alauddin

had lost the battle even though Chittor became Islam.

Srinivasan

demonstrated that Padmavat has

undergone several mutations and translations between sixteenth and twentieth centuries

where the representation of Alauddin Khilji has attracted a lot of attention. His

portrayal to conquer Chitor and the surrender of Padmavati invoked the defense

of Rajput valor and pride. Rajput veerta

(chivalry) depended on the ability to protect the women. The effort to

historicize Padmavat has turned

Jayasi into a defender of Hindu culture, sati (widow-burning),

and masculinity.

demonstrated that Padmavat has

undergone several mutations and translations between sixteenth and twentieth centuries

where the representation of Alauddin Khilji has attracted a lot of attention. His

portrayal to conquer Chitor and the surrender of Padmavati invoked the defense

of Rajput valor and pride. Rajput veerta

(chivalry) depended on the ability to protect the women. The effort to

historicize Padmavat has turned

Jayasi into a defender of Hindu culture, sati (widow-burning),

and masculinity.

The trailer of Padmavati

and Islamophobia

and Islamophobia

The trailer of Padmavati

has again reminded us of the horrors of Muslim representation in Bollywood

films. In the trailer,Alauddin Khiljii’s an aggressive and ruthless ruler. In

sharp contrast, Professor Irfan Habib has demonstrated that Alauddin Khilji’s

territorial expansion was associated with the expansion of fiscal resources.

Tax rent was imposed over a large area and fiscal claims of hereditary

intermediaries (chaudhuris) and

village headmen (khots) were heavily

curtailed. The tax grain was so large in quantity that by controlling its

supply and price, he was able to control the prices of commodities in Delhi. Moreover,

the ruling elite included people outside Turkish origins and Alauddin exercised

complete control over religious scholars. Chronicler Barni lamented that sharia (Islamic law) was no longer

followed in governing the country. Srinivasan argues that it was only in the sixteenth

century that Alauddin’s conquests were actively constructed in Rajput memory. Several

recent writings on the film Padmavati

has overlooked how the valorization of Rajput culture created a strong

environment of portraying the medieval period as oppressive and barbaric.

has again reminded us of the horrors of Muslim representation in Bollywood

films. In the trailer,Alauddin Khiljii’s an aggressive and ruthless ruler. In

sharp contrast, Professor Irfan Habib has demonstrated that Alauddin Khilji’s

territorial expansion was associated with the expansion of fiscal resources.

Tax rent was imposed over a large area and fiscal claims of hereditary

intermediaries (chaudhuris) and

village headmen (khots) were heavily

curtailed. The tax grain was so large in quantity that by controlling its

supply and price, he was able to control the prices of commodities in Delhi. Moreover,

the ruling elite included people outside Turkish origins and Alauddin exercised

complete control over religious scholars. Chronicler Barni lamented that sharia (Islamic law) was no longer

followed in governing the country. Srinivasan argues that it was only in the sixteenth

century that Alauddin’s conquests were actively constructed in Rajput memory. Several

recent writings on the film Padmavati

has overlooked how the valorization of Rajput culture created a strong

environment of portraying the medieval period as oppressive and barbaric.

Padmavati

is not the first film that has stereotyped Muslims. After the Babri Masjid

demolition in 1992 followed by 9/11, several Hindi movies such as Zameen (2003) and Dhokha (2007) established a strong relationship between Islam and

terrorism. Fanaa (2006) and Kurban

(2009) depicted Muslims as having beards, being terrorists, and homes in Muslim

localities usually have the Pakistan flag. Deepa Kumar argues that post 9/11

Islam is equated with religious hysteria and terrorism. In India, Bollywood has further solidified

that image by portraying Islam negatively and Muslims as terrorists. Recently,

even regional movies such as Zulfikar,

made in Bengali, stereotyped Muslims for being criminals and engaging in

smuggling activities.Hindus and Muslims

have been portrayed as mutually exclusive religious groups always at war with

each other. To quote HarbansMukhia “All we have right now are loud screams on

TV channels and periodic declarations by non-historians that all history has so

far been a distorted version.”1

is not the first film that has stereotyped Muslims. After the Babri Masjid

demolition in 1992 followed by 9/11, several Hindi movies such as Zameen (2003) and Dhokha (2007) established a strong relationship between Islam and

terrorism. Fanaa (2006) and Kurban

(2009) depicted Muslims as having beards, being terrorists, and homes in Muslim

localities usually have the Pakistan flag. Deepa Kumar argues that post 9/11

Islam is equated with religious hysteria and terrorism. In India, Bollywood has further solidified

that image by portraying Islam negatively and Muslims as terrorists. Recently,

even regional movies such as Zulfikar,

made in Bengali, stereotyped Muslims for being criminals and engaging in

smuggling activities.Hindus and Muslims

have been portrayed as mutually exclusive religious groups always at war with

each other. To quote HarbansMukhia “All we have right now are loud screams on

TV channels and periodic declarations by non-historians that all history has so

far been a distorted version.”1

Colonial Legacy, Hindutva, and the World’s Largest Democracy

The

controversy over Padmavati shows how communal

conflict, a legacy of British rule, haunts us even today. Barbara Metcalf argues

that nationalist historians found it useful to accept the periodization of

Indian History by the British. The Indian Golden Age followed by oppressive

Muslim rule provided a sense of Hindu cultural pride. Furthermore, the history

of Muslims has been reduced to words such as “fanatic” “militaristic,” and

“monolithic.”After the Babri Masjid demolition, Bal Thackeray of Shiv Sena said

“if Muslims behaved like Jews in Nazi Germany, there would be nothing wrong if

they were treated as Jews were in Germany.”2 Muslims have been openly

demonized, and the notion of a secular past have been consciously subverted to

portray Muslims as enemies of Hindus. The community oriented identity politics

that emerged under colonial rule only helped Vishwa

Hindu Parishad (right wing Hindu organization) and Sangh Parivar leaders to

sharpen their trishuls (three wedged

sword).

controversy over Padmavati shows how communal

conflict, a legacy of British rule, haunts us even today. Barbara Metcalf argues

that nationalist historians found it useful to accept the periodization of

Indian History by the British. The Indian Golden Age followed by oppressive

Muslim rule provided a sense of Hindu cultural pride. Furthermore, the history

of Muslims has been reduced to words such as “fanatic” “militaristic,” and

“monolithic.”After the Babri Masjid demolition, Bal Thackeray of Shiv Sena said

“if Muslims behaved like Jews in Nazi Germany, there would be nothing wrong if

they were treated as Jews were in Germany.”2 Muslims have been openly

demonized, and the notion of a secular past have been consciously subverted to

portray Muslims as enemies of Hindus. The community oriented identity politics

that emerged under colonial rule only helped Vishwa

Hindu Parishad (right wing Hindu organization) and Sangh Parivar leaders to

sharpen their trishuls (three wedged

sword).

The glorification of Rajput valor in Padmavati have

The glorification of Rajput valor in Padmavati havepaved the for the celebration of both jauhar

(self-immolation) and sati. After eighteen-year-old

RoopKanwar (in pic beside) was burned on her husband’s pyre in Deorala, a village in Rajasthan on

September 4, 1987, the members of the Bharatiya Janata Party (right wing Hindu

group) argued that they would oppose any law that prevented Rajputs from

upholding such traditions. Vishwa Hindu Parishad chanted slogans such as “Desh Dharam Ka Nata Hai Sati Hamari Mata Hai”

(Sati empowered Hindu women and was glorified as a mother).3 Huge

sets, cinematic locations, extravagant clothing and jewelry, stellar

photography only indicates the complete amnesia about the lives of women living

in a tradition bound society.

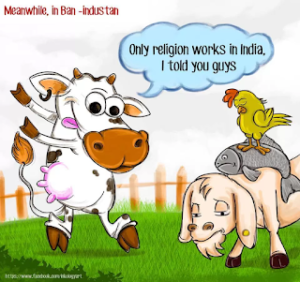

In

2014, the world’s largest democracy voted the Bharatiya Janata

Party to power in the hope of economic growth. Since its election to power,

the government has unleashed terror on the Muslim minority population in the

form of beef ban, arrest of a Muslim doctor for treating children in a government

hospital in Uttar Pradesh that lacked oxygen cylinders, and criminalizing

dissent. In a communally polarized situation, the film Padmavati solidifies the differences between Hindus and Muslims

instead of glorifying a secular past. It also strengthens the neo-patriarchal

offense against women.

2014, the world’s largest democracy voted the Bharatiya Janata

Party to power in the hope of economic growth. Since its election to power,

the government has unleashed terror on the Muslim minority population in the

form of beef ban, arrest of a Muslim doctor for treating children in a government

hospital in Uttar Pradesh that lacked oxygen cylinders, and criminalizing

dissent. In a communally polarized situation, the film Padmavati solidifies the differences between Hindus and Muslims

instead of glorifying a secular past. It also strengthens the neo-patriarchal

offense against women.

Conclusion

The

film has been banned from releasing in five states of India. The system of

banning a film’s release is a threat to the freedom of creativity, expression,

and an attack on democracy. Intellectuals have opposed such threats but there

has been no attempt to engage with issues such as caste oppression, demonizing

minority population,violence against women, and wealth inequality. Moreover,

the film is produced by Mukesh Ambani, the richest man in India, whose wealth

increased by $800 million dollars after BJP came to power. Last time I watched

a Sanjay Leela Bhansali film Devdas, I

cringed seeing inappropriate depiction of the characters on screen. The

controversy over a fictional character has further allowed the Hindutva power to

follow a cultural war of distraction and a policy of divide and rule in an

environment of material hardships and mass unemployment stalking the people of

India under “Acche Din.” (Good Governance Days)

film has been banned from releasing in five states of India. The system of

banning a film’s release is a threat to the freedom of creativity, expression,

and an attack on democracy. Intellectuals have opposed such threats but there

has been no attempt to engage with issues such as caste oppression, demonizing

minority population,violence against women, and wealth inequality. Moreover,

the film is produced by Mukesh Ambani, the richest man in India, whose wealth

increased by $800 million dollars after BJP came to power. Last time I watched

a Sanjay Leela Bhansali film Devdas, I

cringed seeing inappropriate depiction of the characters on screen. The

controversy over a fictional character has further allowed the Hindutva power to

follow a cultural war of distraction and a policy of divide and rule in an

environment of material hardships and mass unemployment stalking the people of

India under “Acche Din.” (Good Governance Days)

(The author is an Assistant Professor of History at University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, USA.)

End Notes

- Harbans Mukhia,

“Stories of a Rajput queen.” The Indian

Express, November 17, 2017. - Barbara

Metcalfe, “Too Little and Too Much: Reflections on Muslims in the History of

India,”The Journal of Asian Studies

54 (1995) 963. - Madhu Kishwar,

Ruth Vanita, “The Burning of RoopKanwar.” Manushi India 42-43 (1987), 17.http://www.manushi-india.org/pdfs_issues/PDF%20files%2042-43/15.%20The%20Burning%20of%20Roop%20Kanwar.pdf (accessed November 26, 2017) - Netty Ismail,

“Mukesh Ambani leads billionaire gains on Narendra Modi’s lead.” Livemint May 14, 2014.

References

1. Habib, Irfan.

Medieval India: A Study of a

Civilization. New Delhi: National Book Trust, 2008.

Medieval India: A Study of a

Civilization. New Delhi: National Book Trust, 2008.

2. Kumar, Deepa.

Islamophobia and the Politics of Empire.

New York: Haymarket Books, 2012

Islamophobia and the Politics of Empire.

New York: Haymarket Books, 2012

3. Metcalfe,

Barbara. “Too Little and Too Much: Reflections on Muslims in the History of

India,” The Journal of Asian Studies

54 (1995) 951-967.

Barbara. “Too Little and Too Much: Reflections on Muslims in the History of

India,” The Journal of Asian Studies

54 (1995) 951-967.

4. Srinivasan, Ramya.

The Many Lives of a Rajput King: Heroic

Pasts in India 1500-1900. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2007

The Many Lives of a Rajput King: Heroic

Pasts in India 1500-1900. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2007