Satyaki Roy and Suchetana Chattopadhyay

Revisiting History

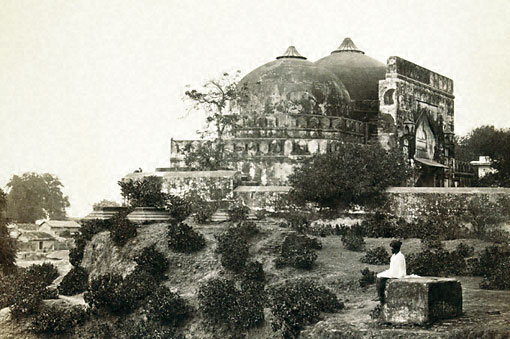

On 6 December 1992, the Hindu fundamentalist forces in India destroyed Babri Masjid, an Islamic monument built in 1528 at Ayodhya. The Hindu communal forces claimed a Ram temple constructed on the holy site of Ram’s birth-place (janmbhoomi) had been destroyed by Babur to build a mosque. This ‘historic hurt’ had to be corrected by destroying the medieval mosque and building a modern temple in its place. The claim was reinforced with spurious archaeological pseudo-evidence. The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), a body over which Hindu communal bias exercises significant dominance, along with the Hindu fundamentalist groups, have argued that the existence of the temple can be proved on the basis of certain ‘pillar bases’. B.B. Lal, the ex-director-general of the ASI, who first excavated the Ayodhya site, in his first report did not even mention them. Soon after the shilanyas for the proposed temple in November 1989 by the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP), Lal published a paper in 1990 in an RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh) mouthpiece. This was almost 15 years after his excavation. He suddenly referred to a pillared structure adjoining the mosque. The 14 black stone pillars with non-Islamic motifs which four senior secular historians and archaeologists found embedded at the arched entrances of the mosque turned out to be decorative pieces incapable of bearing loads. When the four historians wanted to examine them and other features further, the ASI withheld the site notebook from them. All credible archaeological digging pointed at older mosque-like structures under the Babri Masjid. The UP government led by the BJP presided over the destruction of the mosque and the pogroms against Muslims that immediately followed. The central government led by the Indian National Congress did nothing to stop the planned demolition of the mosque. As communal polarisation gripped the country, an orgy of violence was unleashed on Muslims. While the flames of anti-minority hatred spread from Bombay to Surat, the BJP emerged as a national party for the first time. The BJP made communalism respectable in post-Independence India at a crucial moment. This was systematically undertaken at a time when the older Nehruvian institutions were on the eve of being dismantled by the Indian National Congress. The moment was not without irony. A convergence of neoliberal and hindu majoritarian affinities could be witnessed during 1990 in BJP’s rathyatra (country-wide campaign to build a Ram temple at the site of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya) when senior BJP leader and old RSS hand L. K. Advani went around riding a make-shift DCM-Toyota van masquerading as a Chariot. Among the many RSS pracharaks (campaigners) accompanying him were two unknown faces from Gujarat-Narendra Damodardas Modi and Amit Shah who have now displaced the old guard, including Advani. The BJP’s main plank was to devise a scheme whereby religious minorities could be disenfranchised and stripped of citizenship. While Muslims had been subjected to repeated pogroms since Independence and Partition (1947) and projected as ‘outsiders’, the Ram temple issue, for the first time turned the latent communal hatred towards them into a mainstream scapegoating campaign.

No evidence shows that Ayodhya was a significant Brahmanical pilgrimage centre even as late as the eighteenth century. Ayodhya was an important early medieval Buddhist centre. Huen Tsang, the Chinese pilgrim referred to 100 Buddhist monasteries but only ten abodes of Brahmanical gods in this town during the seventh century. Jains claimed it was the birth-place of Rishabnath, their first Tirthankar. Abul Fazl referred to two Jewish prophets buried at Ayodhya. Ayodhya was called Awadh in the pre-colonial era. Tulsidas’s Ramcharit Manas refers to the town as Awadh-puri. It was a flourishing medieval town and housed a sizable Muslim population. Babur’s general Mir Baqi constructed a large mosque here; it became known as the Babri Masjid. The construction of the mosque, proclaimed in two Persian inscriptions, on the pulpit and the gate, said nothing about the destruction of a temple.

Ayodhya’s identification with the birth-place of Ram developed late and long after the Babri Masjid was built. In the early seventeenth century, among 30 sites in Ayodhya only one claimed to be the site of Råm’s birthplace. In the latter half of the eighteenth century, a European traveller alleged that a temple had been destroyed to construct a mosque by either Båbur or Aurangzeb. A communal clash in 1855 made the Nawab of Awadh’s officers settle the issue by letting idols to be placed outside the mosque. This site came to be known as Sita-ki-rasoi (Sita’s kitchen). A trust (waqf) was created for the maintenance of the mosque. In 1884, this status quo was upheld by the colonial judiciary. In the 1930s, at a time of communal rioting, a Hindu mob entered the mosque and destroyed the Persian inscription on the pulpit. However, Muslims continued to pray in the mosque. This was the situation till December 1949. During the night of 22-23 December1949, Hindu communal forces broke open the locks and entered the mosque. They placed the idols of Sita-ki-rasoi within the mosque close to the pulpit. This effectively put a stop to Muslim worship inside the mosque. The mosque remained closed till 1986 when KM Pandey, a district judge, gave an order to unlock the mosque so that Hindus could worship the idols. This was implemented by the Congress government at the Centre led by Rajiv Gandhi. This judgement excluded Muslims from entering the mosque and practically turned the Babri Masjid into a site of Hindu worship. The RSS-controlled BJP and VHP took this process of take-over forward, spearheading a communal campaign to demolish the mosque and build a temple in the course of 1989-1992.

After they demolished the mosque on 6 December1992, a case of ‘property dispute’ on the possession of the site began. In 2010, the Allahabad High Court decided to assign two-thirds of the land to the Hindu fundamentalist forces who had advocated and carried out the destruction of the mosque. On 9 November 2019, the constitution bench of the Supreme Court ruled entirely in their favour and handed over the land to the BJP-ruled central government, recommending the construction of a temple.

Verdict in its Own Words

The historic verdict on Ayodhya title suit is a landmark in the history and polity of Independent India as it claims to resolve a prolonged conflict between Hindus and Muslims spanning four distinct legal regimes under the rule of Vikramaditya, the Mughals, the British period and Independent India. Based on the evidence submitted by both sides on property rights the judgment acknowledges the fact the rights could not be established prior to the British period. The judgment says that property rights if there may be any do not get carried over automatically in subsequent regimes if it is not explicitly recognised by subsequent regimes. As the judgment states:

The legal consequences of actions taken, proprietary rights perfected, or injuries suffered in previous legal regimes can only be enforced by this Court if they received implied or express recognition by subsequent sovereigns. Absent such recognition, the change of sovereignty is an act of State and this Court cannot compel a subsequent sovereign to recognise and remedy historical wrongs. (para 646, pg. 766)

On the basis of this principle examining all the submissions of both the plaintiffs the judgment further says:

No argument other than a bare reliance on the ASI report was put forth. No evidence was led by the plaintiffs in Suit 5 to support the contention that even if the underlying structure was believed to be a temple, the rights that flow from it were recognised by subsequent sovereigns. The mere existence of a structure underneath the disputed property cannot lead to a legally enforceable claim to title today. (para 648, pg 767).

It is only with respect to the change of sovereign from the British colonial regime to Independent India there exists a line of continuity which is laid down in Article 372 of the Constitution. This guarantees the continuity of private property rights that existed in British India. The verdict refers to the historical fact that the construction of railing dividing the disputed property during British rule suggests that the British Sovereign recognised and permitted the existence of both Hindu and Muslim communities at the disputed property in 1856.

Referring to the historical evidence cited by ASI the judgment comments

A finding of title cannot be based in law on the archaeological findings which have been arrived at by ASI. Between the twelfth century to which the underlying structure is dated and the construction of the mosque in the sixteenth century, there is an intervening period of four centuries. No evidence has been placed on the record in relation to the course of human history between the twelfth and sixteen centuries. No evidence is available in a case of this antiquity on (i) the cause of destruction of the underlying structure; and (ii) whether the pre-existing structure was demolished for the construction of the mosque. (para 788III, page 907).

Therefore, the judgment makes it amply clear that based on archaeological evidence or on the basis of documentary evidence property right of none of the parties are being established. The judgment then proceeds by making a conclusive observation in this stage:

Where the existing statutory framework is inadequate for courts to adjudicate upon the dispute before them, or no settled judicial doctrine or custom can be availed of, courts may legitimately take recourse to the principles of justice, equity and good conscience to effectively and fairly dispose of the case. A court cannot abdicate its responsibility to decide a dispute over legal rights merely because the facts of a case do not readily submit themselves to the application of the letter of the existing law. (para 673, page 787) The concept of justice, equity and good conscience‘ as a tool to ensure a just outcome also finds expression in Article 142 of the Constitution…(para 674, page 788).

In other words, when the title of the disputed property could not be resolved under the existing framework of law the Supreme Court uses its special provision laid down in Article 142 to adjudicate the title matter on the basis of ‘equity justice and conscience’ and the judgement refers to ample cases where such adjudications are being made.

Then the judgement takes a different turn where provisions of possession and adverse possession are being invoked to address the question of continuity of possession spanning a period of 450 years and beyond. It says that complete justice requires a wide amplitude and encompasses a power of equity which is employed when the strict application of the law is inadequate to produce a just outcome. The demands of justice require a close attention not just to positive law but also to the silences of positive law to find within its interstices, a solution that is equitable and just. (para 674, page 788.).

The observations of the Constitution Bench thereafter focus on evidence and counter evidence of both parties on the continuity of possession and tried to resolve the title deed as stated below

In the absence of historical records with respect to ownership or title, the court…has to determine the nature and use of the disputed premises as a whole by either of the parties. In determining the nature of use, the court has to factor in the length and extent of use. (para 771, page 883).

What the judgment therefore wanted to examine is the continuity of use of both parties in possessing the disputed structure spanning a period of more than 450 years. What is surprising is that while stating the scope of the judgment the verdict says:

This Court cannot entertain claims that stem from the actions of the Mughal rulers against Hindu places of worship in a court of law today. For any person who seeks solace or recourse against the actions of any number of ancient rulers, the law is not the answer. (para 652, page 770).

While analysing the evidence submitted by both parties on the question of possession the judgment acknowledges repeated interruptions caused by unlawful acts committed by the Hindus that disrupted religious worship of the Muslims in the disputed site. It also takes note of the fact that

The contestation over the possession of the inner courtyard became the centre of the communal conflict of 1934 during the course of which the domes of the mosque sustained damage as did the structure. (para XV page 912). It also states The damage to the mosque in 1934, its desecration in 1949 leading to the ouster of the Muslims and the eventual destruction on 6 December 1992 constituted a serious violation of the rule of law. The judgment explicitly condemns the unlawful act committed by the Hindus and how the petitions of the Muslims in this regard were not adequately addressed by the local courts. It finally says,

On 6 December 1992, the structure of the mosque was brought down and the mosque was destroyed. The destruction of the mosque took place in breach of the order of status quo and an assurance given to this Court. The destruction of the mosque and the obliteration of the Islamic structure was an egregious violation of the rule of law (para XVII, 913-14 page). The verdict further states

During the pendency of the suits, the entire structure of the mosque was brought down in a calculated act of destroying a place of public worship. The Muslims have been wrongly deprived of a mosque which had been constructed well over 450 years ago. (page 922).

All these facts provide ample evidence that offerings of prayer by the Muslims were repeatedly disrupted by the organised Hindu forces backed by the local administration. But the final verdict invokes the provisions of possession and adverse possession to judge the continuity of prayers and presence of both parties being blind to the unlawful acts that caused the Muslims discontinue religious practice in the disputed site.

It finally concludes that The Hindus have established a clear case of a possessory title to the outside courtyard by virtue of long, continued and unimpeded worship at the Ramchabutra and other objects of religious significance. The Hindus and the Muslims have contested claims to the offering worship within the three domed structure in the inner courtyard. The assertion by the Hindus of their entitlement to offer worship inside has been contested by the Muslims. In other words, the judgment could not ascertain exclusive possession of the Hindus on the disputed site in its entirety.

In an atmpsphere of rabid majoritarian hatred and violence against religious minorities and political dissidents, this judgement, pronounced a day before Fateha Doaz Daham, can be read as the end of the secular state in India. Those who have come to power by carrying out the destruction of a historic monument and bringing about communal bi-polarisation of society at every level on a mass scale have been rewarded for their efforts. Not a single culprit involved in the mosque demolition, related hate speech and acts of rioting, arson and murder has been punished. Some of the most prominent faces of the mosque demolition movement, accused in multiple cases of inciting communal pogroms, have issued statements expressing great joy and satisfaction. The content of the judgement itself is contradictory since ‘Muslim possession’ of the mosque was continuous from 1528 to 1949. The idols were placed outside the mosque in the nineteenth century and were not placed inside before 1949 and certainly not worshipped before 1986. The verdict is even more staggering since the court has admitted that the placing of idols inside the mosque in 1949 and demolition of the mosque on 6 December 1992 were unlawful acts and the archaeological ‘data’ cited by ASI and the Hindu groups do not prove in any way that a temple existed at the site in the twelfth century and was destroyed to construct the mosque in the sixteenth century.

Homogenising ‘insiders’: Neoliberalism and Hindutva

The message of this verdict is clear and simple. Even if the property right is not being established on the basis of evidence, Hindus are given the title of the disputed land because they were consistent about their faith and have enforced their claim of possession through the entire period as has been suggested by some travelogues and hearsay. The Muslims could not establish their continued presence even if the court acknowledges that their religious practice was interrupted through violent acts of organised Hindu forces in different phases of history and local administrative interference in favour of the latter in the post-Independence period. Contrary to what the judgment suggests in one part, that the court of law today cannot resolve historical wrongs by rulers in ancient periods (even if it is established), it says that it had to adjudicate the matter and resolve the issue forever.

The apparent legal resolution raises fundamental question on the role of the secular state which is supposed to be neutral on matters of religious beliefs and ensures equal rights for all communities in Independent India. But here the rule of law seems to be subservient to a majoritarian aggression driven by continuity of faith. And the verdict seems to be insensitive to the fact of encroachment of one faith by another. What is also important is that it opens up a new debate where all monuments constructed during the Sultanate and Mughal period would be questioned invoking the question of intrusion into Hindu land. Whether this would be legally tenable or not given the The Places of Worship (Special provisions) Act 1991 which prohibits conversion of any place of worship as it existed during the emergence of Independent India is a legal as well as political question. The Babri masjid was kept aside as an ‘exception’. The political mobilisation against Muslims by the Hindu rightwing forces at least gains moral traction through the current verdict. Underlying the ‘peace and tranquillity’ which many people think has been ensured by this verdict is the recognition of the sentiment of the dominant religious group while what minorities are forced to accept is that they have to buy peace by accepting India as essentially a Hindu land.

The supplanting of a formally neutral state by a ‘historic bloc’ with multiple class fractions where a fundamentalist Hindu identity becomes dominant while all other interests and identities becomes subordinate is the real danger that the country is currently facing. Once this becomes the fundamental identity of being Indian, existing institutions of opinion building through democratic processes become essentially futile. Political oppositions become increasingly sensitive to the ‘Hindu sentiment’ which further legitimises mobilisation on the basis of religion. The primacy of Hindu concerns and symbols in the political discourse displaces all other crucial issues of economy, polity and culture. The ‘Hindu voter’ displaces the secular Indian citizen and the field of democracy is radically altered by overriding concern of Hindu majoritarian sentiments. This is in conformity with what the Nazi propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbles once said ‘This will always remain one of the best jokes of democracy, that it gave its deadly enemies the means by which it was destroyed’.

Neoliberalism in India entails a ‘market society’ and the construction of a monolithic ‘Hindu society’ supplements the same process by homogenising individuals and ripping off other structural social identities based on class, caste and gender. The RSS project of creating a ‘good Hindu’ as a social construct essentially subsumes all contestations of oppression and exploitation by means of creating the ‘hindu individual’ insensitive to class, caste, gender and religion based oppressions. It makes the majoritarian state appear as the coordinator and defender of this homogeneous ‘individual’ whose social existence can only be realised by the market forces. Thus the hegemonic bloc maintains its stability by invoking successive doses of legal and extra-legal interventions that coordinates the interests of the subordinated segments and conditions them according to the dominant discourse of Hindutva; it makes them internalise the logic of the presumed ‘Hindu land’. The process in effect helps displacing grievances that result from the rising inequality in a neoliberal regime. The Hindutva process of mythologisaton of history and identifying ‘outsiders’ is a grand project of homogenising the ‘insiders’. It not only legitimizes discrimination against ‘outsiders’ but also creates the optical illusion by which all ‘insiders’ appear as equal Hindus. In this process caste, class and gender based oppressions are made invisible or at least subsumed into the dominant conflict against ‘outsiders’.

This exercise is not limited to a cultural project anymore. The social contradictions are mitigated by concrete material interventions that determine gains and losses of individuals in their daily lives. The actualisation of the ‘homogeneous individual’ entails conscious material interventions that apparently displaces structural fissures. It is marshalled by projects, schemes and rewards that tend to dislodge all sorts of oppressed and marginalised collective identities and aims at stitching these heterogeneous and often conflicting identities together into a grand Hindu parivaar. This gives rise to the Hindu individual who becomes blind of structural oppressions and exploitation. This new individual not only explicitly supports and rationalises the destruction of a masjid but also happily accepts the destruction of the state of Jammu and Kashmir just because it is a Muslim majority state. For the same reason, he legitimizes a state sponsored perpetual terror on the people of Kashmir valley and turns a blind eye to the enormous violation of human rights that continues for months. The new Hindu citizen rationalises the call for multiple documentary evidence to pass the test of citizenship for individuals residing in India for generations while accepting the existence of Ram Lala simply on the basis of faith. The current verdict ascertains possession based on continuity of faith that overrules absence of legal rights in Ayodhya. This converges with the non-execution of a court’s verdict on the basis of faith as in the case of Sabarimala. All this signals the emergence of a new India where the Hindutva project continuously manufactures new ‘outsiders’ who would be stripped of citizenship and thrown into ‘detention camps’ and the status of immigrants are to be judged on the basis of religion.

Silence on oppressions based on religion, caste, and gender would not help foregrounding the battle against inequality and exploitation that presumes secular democratic principles. The generation of secular consciousness demands a battle in the created field itself. Contesting the process of constructed homogenisation requires emphasising the secular content in day to day life rather than conceiving it as a cultural battle between modernity and faith. Since the faith of Hindu India corroborates the ‘rationality’ of the market, the economic process cannot be separated from the political, cultural and ideological processes which mutually constitute each other.

This brings us back to the ruins of Babri Masjid. We are forced by the times to engage with a counter-factual, counter-historical, rhetorical yet pressing social and political question: if a temple had existed under the mosque, could the demolition of the mosque be interpreted as a justifiable act? The answer is firmly in the negative. Modern political forces always turn to the distant past that no longer exists for opportunistic reasons. The past is in ruins and sectarian divisions from the pre-colonial period cannot be evoked to justify current communal criminality and violence. The BJP and the Sangh Parivar are modern creations. Even the founding ideological networks behind them emerged gradually in the colonial era, with full backing of the British colonial state, between the 1870s and 1925. As mentioned, their economic agenda is in conformity with the late capitalist ‘global’ neoliberal turn; the religious forms of the ‘cultural nationalism’ they invoke are of a kitschy modern consumerist kind. Clearly, it is not history that moves them but super profits to be accrued in the present. If distortion of the past is their starting point, then annihilation of the past is their clear destination. In order to impose myth over history, they will, sooner or later, damage through invasive alteration and actively destroy all historic monuments and relics of the past of all religious denominations that still stand in India. This takes us to the next question: where else may this lead? If the past is to be ‘revived’ in this manner, then every historic Brahmanical temple will have to be dug up. They will have to be uprooted to check if Buddhist/Jain sites or older Brahmanical temples belonging to minor or defeated sects or Sudra and adivasi domiciles were destroyed to build them and the sites ‘returned’ to other modern claimants. Will the ASI show the same enthusiasm for such projects? Will such acts of ‘property dispute’ be entertained by the powers that be? If we turn to the easily traceable present, how would it feel if the slums and villages being demolished to build skyscrapers and giant statues by the favoured corporate builders or mines and natural resources appropriated by big corporations are claimed by the dispossessed as the sites of their janmabhoomi? Will that please our current rulers?

This brings us back to the ruins of Babri Masjid. We are forced by the times to engage with a counter-factual, counter-historical, rhetorical yet pressing social and political question: if a temple had existed under the mosque, could the demolition of the mosque be interpreted as a justifiable act? The answer is firmly in the negative. Modern political forces always turn to the distant past that no longer exists for opportunistic reasons. The past is in ruins and sectarian divisions from the pre-colonial period cannot be evoked to justify current communal criminality and violence. The BJP and the Sangh Parivar are modern creations. Even the founding ideological networks behind them emerged gradually in the colonial era, with full backing of the British colonial state, between the 1870s and 1925. As mentioned, their economic agenda is in conformity with the late capitalist ‘global’ neoliberal turn; the religious forms of the ‘cultural nationalism’ they invoke are of a kitschy modern consumerist kind. Clearly, it is not history that moves them but super profits to be accrued in the present. If distortion of the past is their starting point, then annihilation of the past is their clear destination. In order to impose myth over history, they will, sooner or later, damage through invasive alteration and actively destroy all historic monuments and relics of the past of all religious denominations that still stand in India. This takes us to the next question: where else may this lead? If the past is to be ‘revived’ in this manner, then every historic Brahmanical temple will have to be dug up. They will have to be uprooted to check if Buddhist/Jain sites or older Brahmanical temples belonging to minor or defeated sects or Sudra and adivasi domiciles were destroyed to build them and the sites ‘returned’ to other modern claimants. Will the ASI show the same enthusiasm for such projects? Will such acts of ‘property dispute’ be entertained by the powers that be? If we turn to the easily traceable present, how would it feel if the slums and villages being demolished to build skyscrapers and giant statues by the favoured corporate builders or mines and natural resources appropriated by big corporations are claimed by the dispossessed as the sites of their janmabhoomi? Will that please our current rulers? Satyaki Roy is Associate Professor at ISID, New Delhi

Suchetana Chattopadhyay teaches history at Jadavpur University.

References:

Romila Thapar, It has annulled respect for history and seeks to replace it with religious faith

There is no evidence of Temple under Babri Masjid, Just older Mosques: Says Archeologist

Paper I: Misinterpreted and misjudged

Irfan Habib, The Destruction of Babri Masjid – the 25th Anniversary

Babri Masjid demolition: The key political players and their roles

Ayodhya Dispute Is a Battle Between Faith and Rationality, Says Historian D.N. Jha

Babri Masjid demolition case: CBI produces half a dozen witnesses

LK Advani: Hindu nationalism’s original poster boy who could not reap what he sowed