Recent Developments in the Climate Change Discussions and the Indian Case – Tirthankar Mandal

Climate

change has put before the global community an epochal development and

environmental challenge. The overriding complexity of the problem is

attributed to its deeper global ramifications on a vast range of issues

impacting the very survival of life on Earth. Understanding such a complex

issue with vast and varied dimensions and implications, assumes greater

significance for all stakeholders, especially for our policy makers. There are

varieties of perceptions regarding the exact size and consequences of climate

change. Yet, it is no secret that risks emanating from climate change are

indeed profound, which call for urgent mitigation. India, in this whole milieu

of things and complexities, is in a very tricky situation and faces a

multiplicity of challenges. On one hand India is home to a large number of poor

and vulnerable people in the world rendering itself to be affected adversely by

the impacts of climate change, and on the other, to meet the development needs,

India has been arguing that it needs emission space for GHGs for the time to

come in future. This brings to the forefront the question of prioritizing

development versus meeting climate change obligations. In the domain of climate change negotiations,

developing countries, including India have been arguing for the right to

develop, which in turn requires emission space to meet the goals of development. This then requires a share of the burden of

emission reductions between the group of developed and developing countries in

order to avoid violating the planetary boundary limits in future.

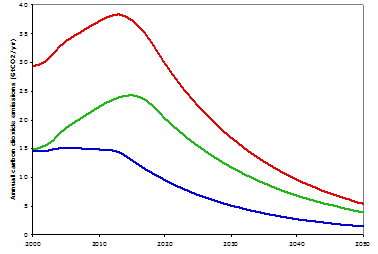

global emission pathway (red line) consistent with a reasonable probability of

keeping warming below 2°C (It assumes a budget of about 1,700 billion tons of

carbon dioxide equivalent (GtCO2e) for the first half of the 21st century, which

still carries an unsettlingly high one-in-four chance that warming will exceed

2°C. It also shows an Annex 1 emission pathway (blue), with the Annex 1

countries undertaking ambitious mitigation actions, sufficient to drive

emissions down by 40 per cent by 2020 and 90 per cent by 2050 (relative to 1990

emission levels). Having stipulated a global trajectory and an Annex 1

trajectory, simple subtraction reveals the carbon budget (shown in green) that

would remain to support the South’s development. Despite the apparent

stringency of the Annex 1 trajectory, the atmospheric space remaining for

developing countries would be alarmingly small. Developing country emissions

would have to peak only a few years later than those in the North – still

before 2020 – and then decline by nearly 90 per cent by 2050. And this would

have to take place while most of the South’s citizens are still struggling to

maintain or improve their livelihoods and raise their material living

standards.

Figure 1: Global Limits of

2 Degree C Pathways

Source: Kartha (2011)[1]

Policymaking:

emissions originating from the big developing countries such as China, India,

Brazil, South Africa, Indonesia, and Philippines to name a few, on the premise

that the recent emissions have seen a larger growth in these countries due to

their increased economic activities, and also in future these are the regions

where the emission is going to grow most. At the same time it has been observed

that the ambition of the global community has been on downward spiral with each

passing climate Conference of Parties (COP) every year (Khor 2013)[2]. This

happened at the backdrop where almost each and every global climate research agency

depicted a picture of increasingly threatened world in the future. For the

developing countries, each COPs turned out to be baby steps while the world

required quantum of progress to avoid the catastrophic climate change.

increasingly getting non-committal about their commitments for emission reduction

as required by science and on the other there has been increased pressure by

the global communities for enhanced emission reductions by the large developing

countries due to their current emission growth. On another count, the developed

countries have been also non-committal on the support through finance and

technology for the developing countries to take up enhanced actions on climate

change. This has resulted in breach of trust between the developed and the

developing countries to develop a global effort sharing mechanism through these

negotiations.

change negotiations is often being questioned. India is among those countries

of the world, which has seen exponential growth in its current emission of GHG

(Dubash 2009)[3].

Indian position has been rooted in the belief that the focus of burden sharing

should be based on equitable and fair principles of global effort sharing. The

core of this argument, according to India, lies in the historical

responsibility of developed countries that have occupied bulk of the

atmospheric space due to the emissions of the past. Due to this skewed situation, coupled with

rising trends of future emissions, India has been demanding a deep cut from the

developed countries to compensate their past emissions. This will ensure that

adequate atmospheric space is available for the developing countries like India

to grow and meet their developmental needs. In this regard it is also necessary to put the

bigger picture of emissions scenarios against the context of developmental

needs and climate change.

(2013)[5], it has

been observed that the countries are falling short of the emissions as required

by science. Even if the developed countries meet their higher end of the

targets there would be substantial gap in meeting the levels of emissions

reductions as required by science. This brings us back to the situation where

the developing countries would need to take up ambitious emissions reductions

for keeping the limits of temperature rise to 2 degree C of the pre-industrial

level. Therefore, countries like India and others need to enhance their

emission reduction efforts to meet the gap. India has been arguing that

development goals are priority and the developed countries must take up the

lead in emission reductions.

countries are based on the principles and provisions of the Convention. Of late

India has been championing the cause of equitable sharing of emission

reductions burden based on the principles of the Convention. This has been the

core fundamental of the agreement at Durban in 2011. However, the Durban

agreement marks a shift from what India has been arguing till recently that the

current cause of emissions and adverse changes in the climate are more due to

the stock of carbon and GHGs that has been accumulated historically and not

because of the current emissions and therefore, the developed countries should

take the onus of reductions. The Durban agreement adopts a stance which

iterates that the principles of equity in efforts to reduce the emissions

should rule the emissions reductions paradigm of the future. In this regard,

however, India has not come forward with a proposal about how to operationalize

the principles of equity as laid down in the Convention which will meet the

objectives of development and also keep the global emissions under admissible

levels. It is seen by the global community as tactics to delay the

negotiations, but there is no denial of the fact that the developed countries

have also not lived up to their leadership role as they are supposed to be

doing.

technology for undertaking climate actions in the developing countries has been

at the core to develop a fair and equitable mechanism globally. In this case as

well, the developed countries have performed miserably. Except for setting up

structures of global finance and technology mechanism there has been little

progress over the last few years. Further, the global finance mechanism and the

technology mechanism is seen as a half-baked cake as they do not have the

adequate amount of funding available for supporting actions in the developing

countries. This has not gone down well with the countries like India, China,

and other big developing countries as they consider this as breach of trust

from the developed country counterparts.

the lack of political will and trust among the countries. On one hand the

developed countries have been minimally ambitious in putting the targets of

emission reductions for their own, and on the other, putting pressure on the

developing countries to meet the gap that is emerging on the premise that the

current emission for these developing countries are more than their own share.

Secondly, the developed countries have not performed on allocating funds and

technology support for climate actions in the developing countries. Therefore whenever a discussion on emission

reduction happens within the climate regime, the developed countries have

failed to assure the developing countries about science-based actions to save

the global community from catastrophes.

discussion that would identify the operationalization of equitable effort

sharing mechanism in emission reductions. For India, it could mean coming out

with clear vision of emission reductions which will state its priorities both

globally and internationally. Also the actions it has been undertaking recently

under various fronts should be properly communicated. Currently the country is

seen as obstructionist force. It therefore requires changing the views towards

becoming constructionist one and also not compromising on the developmental

goals it has set for countries.

communicating to the world about its actions on climate change and its

obligations domestically. The global community has been getting mixed views

about the country. On one hand India has been claiming the inability to

undertake deeper cuts on the premise of immediate development needs and lack of

capacity, on the other, it wants to evolve as global power. Being a global

power send a different signal about the overall capacity and capability of a

country. In the domain of climate change this positioning of India is slightly

problematic and should be more strategic. It should clearly lay down the

actions it has been undertaking and communicate to the world about its

intention to undertake further actions with appropriate conditionality so that

it need not compromise on the development goals.

with the countries from the blocs like Small Island states, LDCs, and other

vulnerable countries as they form a substantial force within the G77 and China

which India is also part of. This would ensure that the predicaments of India

are well understood and we can avoid a situation where these countries stood

firmly behind the collective positions of G77 and China at the negotiations.

One of the fears the vulnerable groups of countries from Small Islands, LDCs

perceive is that the big developing countries will attract all the

international climate finance available and this fear needs to be addressed at

the earliest to keep the coalition of the developing countries intact so that

adequate pressure can be put against the low level of ambition for the

developed countries. This is a situation where developing countries cannot

afford to be seen as a divided house.

Handbook of Climate Change and Society edited by John S. Dryzek, Richard B. Norgaard, & David Schlosberg

Ambitions, Economic and Political Weekly, Jan 12, 2013, XLVIII No.2

Progressive Global and Indian Politics, Working Paper (2009/1), CPR Initiative, CPR, New Delhi.