Shailender Kumar Hooda

Most countries in the world

spend a sizable amount of public fund on health, though delivery of health

services is organised through a mix of government and private providers. The countries recording high level of public

spending in health have secured better health outcomes compared to the

countries with low spending, barring few exceptions like the US, where high

public spending co-exists with high exclusion. Some however have also managed

better outcomes with little public funds while improving allocation of funds,

better management and effective service delivery mechanisms (NCMH, 2005). India’s

performance in improving the health outcomes, even after announcement of more

than 21 committees and commissions on health sector reforms, has remained far

from satisfactory levels. For instance, some of the health outcomes (infant,

child and maternal mortality rates) are not only lower than the Millennium

Development Goal targets but even worse than some of the developing countries.

The infant mortality rates (IMR) of India

is around 54 whereas Sri

Lanka’s IMR is 17 (WHR, 2010). The life

expectancy at birth (64 years) of an average Indian is at least 15 years lower

than that of developed countries and even lower than the neighbouring Sri Lanka (74

years). Almost half of Indian children suffer from malnutrition which is even worse

than what recorded in some places in Sub-Saharan Africa. More than 50 per cent

of women suffer from anaemia (WHR, 2010). The rural-urban gaps in health

outcomes are not only persisting but have widened over the years. In order to

understand this unsatisfactory performance in the health sector, one needs to

look at the gap between health policy commitments by the government and the

allocation of funds in respective segments.

spend a sizable amount of public fund on health, though delivery of health

services is organised through a mix of government and private providers. The countries recording high level of public

spending in health have secured better health outcomes compared to the

countries with low spending, barring few exceptions like the US, where high

public spending co-exists with high exclusion. Some however have also managed

better outcomes with little public funds while improving allocation of funds,

better management and effective service delivery mechanisms (NCMH, 2005). India’s

performance in improving the health outcomes, even after announcement of more

than 21 committees and commissions on health sector reforms, has remained far

from satisfactory levels. For instance, some of the health outcomes (infant,

child and maternal mortality rates) are not only lower than the Millennium

Development Goal targets but even worse than some of the developing countries.

The infant mortality rates (IMR) of India

is around 54 whereas Sri

Lanka’s IMR is 17 (WHR, 2010). The life

expectancy at birth (64 years) of an average Indian is at least 15 years lower

than that of developed countries and even lower than the neighbouring Sri Lanka (74

years). Almost half of Indian children suffer from malnutrition which is even worse

than what recorded in some places in Sub-Saharan Africa. More than 50 per cent

of women suffer from anaemia (WHR, 2010). The rural-urban gaps in health

outcomes are not only persisting but have widened over the years. In order to

understand this unsatisfactory performance in the health sector, one needs to

look at the gap between health policy commitments by the government and the

allocation of funds in respective segments.

Commitments Vs Achievements

Since independence, India followed

a welfare state approach with healthcare falling under the auspices of the

government. Healthcare was supposed to be the responsibility of central and

state governments, particularly in determining priorities, financing and

delivery of health services to the general population. The recommendations of

first Health Planning and Development Committee (Bhore Committee, 1946) report,

that emphasised the development of basic infrastructure and manpower, were

taken up in the First (1951-56) and the

Second (1956-61) Five-Year plans of India. Data shows that prescribed

norms of health infrastructure could not be met even after sixty years of

independence, in 2010. Under the Community Development Programme (1951-55), India formulated

a plan to achieve one PHC (Primary Health Centre) per one lakh population, but

the achievement is around one-fifth (one PHC per 5.5 lakh population) of the

targets set for the year 2010. Surprisingly, based on the recommendations of

various committees and Alma-Ata declaration

(1978), India

announced its first formal National Health Policy (NHP) in 1983. NHP pledged to

achieve ‘Health for all by the year 2000’, the primary vehicles conceived were

introduction of certain numbers of CHCs (Community Health Centre), PHCs and SCs

(Sub-centres) in the country. A shortfall of 4372 CHCs, 1875 PHCs and 10992 SCs

was noticed in 2001. Furthermore, as per Indian Public Health Standard (IPHS),

there should be 4-6 beds and 30 beds in each PHC and CHC respectively. In 2010,

only 59 per cent of the PHCs and 72 per cent of the CHCs could achieve the

prescribed standard. Thus the physical and human infrastructure in the health

sector in India

grossly falls short of the prescribed norms.

a welfare state approach with healthcare falling under the auspices of the

government. Healthcare was supposed to be the responsibility of central and

state governments, particularly in determining priorities, financing and

delivery of health services to the general population. The recommendations of

first Health Planning and Development Committee (Bhore Committee, 1946) report,

that emphasised the development of basic infrastructure and manpower, were

taken up in the First (1951-56) and the

Second (1956-61) Five-Year plans of India. Data shows that prescribed

norms of health infrastructure could not be met even after sixty years of

independence, in 2010. Under the Community Development Programme (1951-55), India formulated

a plan to achieve one PHC (Primary Health Centre) per one lakh population, but

the achievement is around one-fifth (one PHC per 5.5 lakh population) of the

targets set for the year 2010. Surprisingly, based on the recommendations of

various committees and Alma-Ata declaration

(1978), India

announced its first formal National Health Policy (NHP) in 1983. NHP pledged to

achieve ‘Health for all by the year 2000’, the primary vehicles conceived were

introduction of certain numbers of CHCs (Community Health Centre), PHCs and SCs

(Sub-centres) in the country. A shortfall of 4372 CHCs, 1875 PHCs and 10992 SCs

was noticed in 2001. Furthermore, as per Indian Public Health Standard (IPHS),

there should be 4-6 beds and 30 beds in each PHC and CHC respectively. In 2010,

only 59 per cent of the PHCs and 72 per cent of the CHCs could achieve the

prescribed standard. Thus the physical and human infrastructure in the health

sector in India

grossly falls short of the prescribed norms.

The second National Health

Policy which was announced in 2002, itself recognised that the performance of

first NHP is unsatisfactory particularly because of low level of government

spending. The second NHP recommended that government spending in health should

increase (i) from its existing level from about 0.9 per cent of GDP to 2 per

cent of GDP and (ii) from existing level of about 5.5 per cent of total budget

spending to 8 per cent of total budget spending by the year 2010. In 2010, the

level of spending recorded to be around 1.09 per cent of GDP which is

significantly lower than the commitments. In 2004-05, the National Commission of

Macro-Economic and Health (NCMH, 2005) of India estimated required level of

resource that need to be spent by every state government to meet the adequate

level of basic health services in the country by the end of 2009-10. An

analysis of the required level of resources against the actual allocation shows

that most of the state governments could not achieve the prescribed level of

health spending during the specified period. Except for Himachal Pradesh, there

exist high gaps between required resources and actual spending in most states (Figure-1). Such gaps in resource

requirements were not only noticed in low income states like Bihar, Orissa,

Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh but the high income states like Punjab and Maharashtra could not maintain the required level of

spending.

Policy which was announced in 2002, itself recognised that the performance of

first NHP is unsatisfactory particularly because of low level of government

spending. The second NHP recommended that government spending in health should

increase (i) from its existing level from about 0.9 per cent of GDP to 2 per

cent of GDP and (ii) from existing level of about 5.5 per cent of total budget

spending to 8 per cent of total budget spending by the year 2010. In 2010, the

level of spending recorded to be around 1.09 per cent of GDP which is

significantly lower than the commitments. In 2004-05, the National Commission of

Macro-Economic and Health (NCMH, 2005) of India estimated required level of

resource that need to be spent by every state government to meet the adequate

level of basic health services in the country by the end of 2009-10. An

analysis of the required level of resources against the actual allocation shows

that most of the state governments could not achieve the prescribed level of

health spending during the specified period. Except for Himachal Pradesh, there

exist high gaps between required resources and actual spending in most states (Figure-1). Such gaps in resource

requirements were not only noticed in low income states like Bihar, Orissa,

Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh but the high income states like Punjab and Maharashtra could not maintain the required level of

spending.

In 2005, central government

launched a flagship programme called National Rural Health Mission-NRHM. The Mission has set an

ambitious goal of increasing in government spending in health to 2-3 per cent

of GDP by 2012. But spending remained 1.2 per cent of GDP at the end of 11th

Plan (2012). Even after adding the expenditure of complementary (water supply

and sanitation) services, the spending hovered around 1.6 per cent of GDP which

is less than the commitment. The failure in various policy commitments reflects

that India,

despite having low health outcomes fails to allocate resources that increase

provisions for health care. Overall, neither the Primary Health Care approach,

‘Health for All’ targets nor the spending commitment ever been implemented and fulfilled

in the country. This reflects that health has always been a low priority sector

in India.

Recently, the High level Expert Groups (2012) on Universal Health Coverage has

proposed to increase the government (central and state combined) spending in

health from the current level of 1.2 per cent of GDP to at least 2.5 per cent

by the end of the 12th Plan and to at least 3 per cent of GDP by

2022. Past experience however leaves little hope in fulfilling these

commitments.

launched a flagship programme called National Rural Health Mission-NRHM. The Mission has set an

ambitious goal of increasing in government spending in health to 2-3 per cent

of GDP by 2012. But spending remained 1.2 per cent of GDP at the end of 11th

Plan (2012). Even after adding the expenditure of complementary (water supply

and sanitation) services, the spending hovered around 1.6 per cent of GDP which

is less than the commitment. The failure in various policy commitments reflects

that India,

despite having low health outcomes fails to allocate resources that increase

provisions for health care. Overall, neither the Primary Health Care approach,

‘Health for All’ targets nor the spending commitment ever been implemented and fulfilled

in the country. This reflects that health has always been a low priority sector

in India.

Recently, the High level Expert Groups (2012) on Universal Health Coverage has

proposed to increase the government (central and state combined) spending in

health from the current level of 1.2 per cent of GDP to at least 2.5 per cent

by the end of the 12th Plan and to at least 3 per cent of GDP by

2022. Past experience however leaves little hope in fulfilling these

commitments.

Figure-1: Resource

Requirements vs. Actual Health Spending across Indian States

Requirements vs. Actual Health Spending across Indian States

Multifaceted

NRHM Initiatives: A Critique

NRHM Initiatives: A Critique

As per the Constitution, health

is a state subject in India.

The state governments would deliver adequate health services to meet the health

need of the population. The central government, however, can directly intervene

in establishing major hospitals and to assist medical education and research.

Another way to intervene in health sector by the central government is to

initiate Central Plan (CPS) and Centrally Sponsored Schemes (CSS), which are generally

implemented through state budgets. Thus the responsibility of fulfilling the

health needs of the population is largely being shifted to the state

governments. In 2005, it was realised that there is high gap in health outcomes

and facilities across Indian states. In order to fill such gap, the central

government, under the NRHM, identified states with high fertility and mortality

rates and otherwise. The former states were named as high focused states-HFS (namely

Assam, Bihar,

Himachal Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh including

north-eastern states) and the rest are non-high focused states (Non-HFS). Under

NRHM, the promise was made to devolve/transfer more central funds towards HFS

to remove variation in health spending across states and to ensure better (up

to the MDGs) health standards in the country. Evidence however shows that the share

of fund allocation remained lower than the commitments made by central

government. Surprisingly, the ratio of actual fund allocation to commitment – a

high ratio reflecting low priority – found high (around 18 percent) in high

focused states as compared to around 15 percent in non-HFS. Even though it was mandated

that the priority should be accorded to high focused states, the outcome was

the opposite.

is a state subject in India.

The state governments would deliver adequate health services to meet the health

need of the population. The central government, however, can directly intervene

in establishing major hospitals and to assist medical education and research.

Another way to intervene in health sector by the central government is to

initiate Central Plan (CPS) and Centrally Sponsored Schemes (CSS), which are generally

implemented through state budgets. Thus the responsibility of fulfilling the

health needs of the population is largely being shifted to the state

governments. In 2005, it was realised that there is high gap in health outcomes

and facilities across Indian states. In order to fill such gap, the central

government, under the NRHM, identified states with high fertility and mortality

rates and otherwise. The former states were named as high focused states-HFS (namely

Assam, Bihar,

Himachal Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh including

north-eastern states) and the rest are non-high focused states (Non-HFS). Under

NRHM, the promise was made to devolve/transfer more central funds towards HFS

to remove variation in health spending across states and to ensure better (up

to the MDGs) health standards in the country. Evidence however shows that the share

of fund allocation remained lower than the commitments made by central

government. Surprisingly, the ratio of actual fund allocation to commitment – a

high ratio reflecting low priority – found high (around 18 percent) in high

focused states as compared to around 15 percent in non-HFS. Even though it was mandated

that the priority should be accorded to high focused states, the outcome was

the opposite.

Under NRHM, under fund

devolution criteria, the central government asked the state to increase their

own spending at a specified rate in tandem with increased central funding. It

was found that state governments are failing in their capacity to absorb the

funds that are allocated by central government. The share of unspent amount

with the state as a ratio of total funds released by central government is

recorded around 6.4 per cent and 12.5 per cent for high focused and non-high

focused states respectively, indicating inadequate absorptive capacity of states

to utilize the fund properly. The absorptive capacity however found to be high

in high focused states compared to the non-high focused states which seem to be

a positive indication. The fund absorptive capacity is noticed to be highly

inadequate in West Bengal and Punjab, where

around 56 per cent and 48 per cent of the funds respectively have not been

utilized. It can be argued that lack of inadequate availability of human

resources, weak capacity to plan and execute plans are plausible reasons for

the state governments failing to absorb the central fund adequately.

devolution criteria, the central government asked the state to increase their

own spending at a specified rate in tandem with increased central funding. It

was found that state governments are failing in their capacity to absorb the

funds that are allocated by central government. The share of unspent amount

with the state as a ratio of total funds released by central government is

recorded around 6.4 per cent and 12.5 per cent for high focused and non-high

focused states respectively, indicating inadequate absorptive capacity of states

to utilize the fund properly. The absorptive capacity however found to be high

in high focused states compared to the non-high focused states which seem to be

a positive indication. The fund absorptive capacity is noticed to be highly

inadequate in West Bengal and Punjab, where

around 56 per cent and 48 per cent of the funds respectively have not been

utilized. It can be argued that lack of inadequate availability of human

resources, weak capacity to plan and execute plans are plausible reasons for

the state governments failing to absorb the central fund adequately.

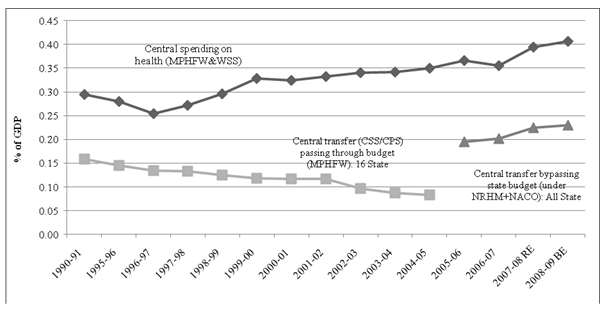

One interesting observation is

that the direction of funds transfer from centre to state has changed

significantly with the implementation of NRHM. Specifically, some of the

central government funds, which were earlier routed through state budget under

the centrally sponsored schemes (CSS) and plan schemes (CPS), now bypasses the

state budgets and are designed to be implemented through state implementing

agencies like State Health Society. Note that the central transfer to states

through CSS/CPS is an important policy initiative of the central government to

support various health programmes running in the state. This helps in meeting

the recurring and non-recurring requirement of these programmes, especially the

programmes related to communicable and non-communicable diseases such as

trachoma, blindness control programmes, family welfare programmes and the

others. With this changing route of central transfer not only it becomes

difficult to comprehend the total government (centre and state) health

expenditure but also entails larger implications for health programmes

initiated by central government. Interestingly central government spending on CSS

and CPS taken together declined from 0.16 per cent of GDP in 1990-91 to 0.08

per cent of GDP in 2004-05 (Figure-2).

This declining share has reduced the budgetary resources provided for dealing

with several existing major communicable and non-communicable diseases and

family welfare programmes. This raises the question of sustainability of some

of the health programmes. Ideally, the long-term sustainability of any one or

all of these central sponsored health programmes, to a large extent, depends on

continuous funding from central government. The declining trends or

uncertainties in resource flows from centre to state would certainly affect the

implementation process and effectiveness of these programs at the state level

and more particularly the needy (poorer) states. This probably indicates that

state governments have to bear most of the burden of health expenditure to

finance these programmes from their own resources.

that the direction of funds transfer from centre to state has changed

significantly with the implementation of NRHM. Specifically, some of the

central government funds, which were earlier routed through state budget under

the centrally sponsored schemes (CSS) and plan schemes (CPS), now bypasses the

state budgets and are designed to be implemented through state implementing

agencies like State Health Society. Note that the central transfer to states

through CSS/CPS is an important policy initiative of the central government to

support various health programmes running in the state. This helps in meeting

the recurring and non-recurring requirement of these programmes, especially the

programmes related to communicable and non-communicable diseases such as

trachoma, blindness control programmes, family welfare programmes and the

others. With this changing route of central transfer not only it becomes

difficult to comprehend the total government (centre and state) health

expenditure but also entails larger implications for health programmes

initiated by central government. Interestingly central government spending on CSS

and CPS taken together declined from 0.16 per cent of GDP in 1990-91 to 0.08

per cent of GDP in 2004-05 (Figure-2).

This declining share has reduced the budgetary resources provided for dealing

with several existing major communicable and non-communicable diseases and

family welfare programmes. This raises the question of sustainability of some

of the health programmes. Ideally, the long-term sustainability of any one or

all of these central sponsored health programmes, to a large extent, depends on

continuous funding from central government. The declining trends or

uncertainties in resource flows from centre to state would certainly affect the

implementation process and effectiveness of these programs at the state level

and more particularly the needy (poorer) states. This probably indicates that

state governments have to bear most of the burden of health expenditure to

finance these programmes from their own resources.

Figure-2:Changing Pattern of Central Transfer to States: Pre

and Post NRHM Analysis

and Post NRHM Analysis

The central spending on NRHM

components that are supposed to be bypassing the state budget and implemented

through state’s autonomous agencies as per cent to GDP has increased during the

period 2005-06 to 2008-09 (Figure-2).

The increasing trend in health expenditure under NRHM, routed through

decentralized agencies, raise doubts about how the implementing agencies will

utilize the transferred funds.

components that are supposed to be bypassing the state budget and implemented

through state’s autonomous agencies as per cent to GDP has increased during the

period 2005-06 to 2008-09 (Figure-2).

The increasing trend in health expenditure under NRHM, routed through

decentralized agencies, raise doubts about how the implementing agencies will

utilize the transferred funds.

As regards to the

sustainability of central sponsored (CSS/CPS) programmes, it has been realised

that NRHM consists of some new schemes but repackages many of the existing

health schemes which are now bypassing the state budget. For instance, the

National Disease Control Programmes (NDCP) which was earlier with the

Department of Health has now been made part of the NRHM. Similarly, the earlier

schemes of the Department of Family Welfare such as reproductive and child

health programme (RCH), immunisation, contraception, information education and

communication (IEC), training and research, area projects and other family

welfare services, are all included in the NRHM. The new initiatives under the

NRHM are mostly financed through what is called the ‘mission flexible pool’

which provides for activities like selection and training of a new cadre of

community health worker called Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA),

up-gradation of health facilities (community health centre and public health centres)

to first referral units (FRU) and facilities meeting the new Indian Public

Health Standards (IPHS), constitution of patient welfare committees called Rogi Kalyan Samiti (RKS) and district

hospital management committees, mobile medical units, united funds for

sub-centres, preparation of district action plans and so forth. There have also

been some changes in the centrally sponsored schemes now falling under the NRHM

umbrella. The earlier RCH programme (RCH1) funded a fixed set of activities.

Under the NRHM, the earlier form of the RCH programme is being phased out. In

RCH2, most activities are funded through an RCH flexible pool which supports

decentralized planning and flexible programming by the states (NRHM, 2005). All

these show that NRHM includes many schemes covered under the CSS/CPS.

sustainability of central sponsored (CSS/CPS) programmes, it has been realised

that NRHM consists of some new schemes but repackages many of the existing

health schemes which are now bypassing the state budget. For instance, the

National Disease Control Programmes (NDCP) which was earlier with the

Department of Health has now been made part of the NRHM. Similarly, the earlier

schemes of the Department of Family Welfare such as reproductive and child

health programme (RCH), immunisation, contraception, information education and

communication (IEC), training and research, area projects and other family

welfare services, are all included in the NRHM. The new initiatives under the

NRHM are mostly financed through what is called the ‘mission flexible pool’

which provides for activities like selection and training of a new cadre of

community health worker called Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA),

up-gradation of health facilities (community health centre and public health centres)

to first referral units (FRU) and facilities meeting the new Indian Public

Health Standards (IPHS), constitution of patient welfare committees called Rogi Kalyan Samiti (RKS) and district

hospital management committees, mobile medical units, united funds for

sub-centres, preparation of district action plans and so forth. There have also

been some changes in the centrally sponsored schemes now falling under the NRHM

umbrella. The earlier RCH programme (RCH1) funded a fixed set of activities.

Under the NRHM, the earlier form of the RCH programme is being phased out. In

RCH2, most activities are funded through an RCH flexible pool which supports

decentralized planning and flexible programming by the states (NRHM, 2005). All

these show that NRHM includes many schemes covered under the CSS/CPS.

A study of expenditure on

different components of NRHM throws some light on the sustainability of earlier

programmes sponsored through CSS/CPS. The NRHM mission flexible pool, which

provides much of “new” funds to the states, accounted a higher amount and shows

increasing trends as per cent to GDP over the period, except for the recent

years. Its share in compositional term has also increased from 13.2 per cent in

2005-06 to 35.2 per cent in 2012-13. The RCH flexible pool, which provides the

greater flexibility to states spending on RCH related activities, has also

constituted higher amount and show increasing trends as per cent to GDP. In

compositional term its share increased from 17.6 per cent in 2005-06 to 26.4

per cent in 2012-13. The expenditure on maintenance of infrastructure however was

on high priority at the time of launch of NRHM. These components constituted

higher amounts as per cent of GDP in 2005-06 but started declining thereafter.

In compositional term, its share stood around half of the NRHM funds (about

46.9%) in 2005-06 but declined to 33.3 per cent in the year 2012-13. One of the

possibilities of decline in expenditure of these components is that central

government has allocated funds on condition that state governments need to

increase their own spending at a specified rate in tandem with the increased

central funding. Inadequate absorptive capacity of state governments probably

has come in the way that expenditure on these components has not been

increased. As regards to the programmes relating to NDCP, the expenditure from

these programmes, in composition term, declined significantly from 14.4 per

cent in 2005-06 to 4.5 per cent in 2012-13. Similar trends are reflected in

case of pulse polio programmes which raises question of sustainability of these

programmes. Therefore, it can be argued that overall increment in expenditure

on NRHM components is positive for health sector but the changing pattern of

health expenditure, through different routes raises issues of sustainability of

some of these programmes and has also made health expenditure more opaque. It

can also be argued that increased funds passing through state implementing

agencies were expected to improve the delivery system of health services in the

rural areas. The outcomes however do not show what was expected rather the

sharing of public health responsibilities between centre and states have made

the process even more cumbersome.

different components of NRHM throws some light on the sustainability of earlier

programmes sponsored through CSS/CPS. The NRHM mission flexible pool, which

provides much of “new” funds to the states, accounted a higher amount and shows

increasing trends as per cent to GDP over the period, except for the recent

years. Its share in compositional term has also increased from 13.2 per cent in

2005-06 to 35.2 per cent in 2012-13. The RCH flexible pool, which provides the

greater flexibility to states spending on RCH related activities, has also

constituted higher amount and show increasing trends as per cent to GDP. In

compositional term its share increased from 17.6 per cent in 2005-06 to 26.4

per cent in 2012-13. The expenditure on maintenance of infrastructure however was

on high priority at the time of launch of NRHM. These components constituted

higher amounts as per cent of GDP in 2005-06 but started declining thereafter.

In compositional term, its share stood around half of the NRHM funds (about

46.9%) in 2005-06 but declined to 33.3 per cent in the year 2012-13. One of the

possibilities of decline in expenditure of these components is that central

government has allocated funds on condition that state governments need to

increase their own spending at a specified rate in tandem with the increased

central funding. Inadequate absorptive capacity of state governments probably

has come in the way that expenditure on these components has not been

increased. As regards to the programmes relating to NDCP, the expenditure from

these programmes, in composition term, declined significantly from 14.4 per

cent in 2005-06 to 4.5 per cent in 2012-13. Similar trends are reflected in

case of pulse polio programmes which raises question of sustainability of these

programmes. Therefore, it can be argued that overall increment in expenditure

on NRHM components is positive for health sector but the changing pattern of

health expenditure, through different routes raises issues of sustainability of

some of these programmes and has also made health expenditure more opaque. It

can also be argued that increased funds passing through state implementing

agencies were expected to improve the delivery system of health services in the

rural areas. The outcomes however do not show what was expected rather the

sharing of public health responsibilities between centre and states have made

the process even more cumbersome.

Concluding Observations

The public expenditure on

health in India

is one of the lowest amongst the many developing countries and from the international

standard of spending. A low level of government spending on health sector seems

to be a generic problem in India.

The individual states were also unable to meet even the minimal level of

resource requirement for maintaining/ providing the basic health facility in

the country. It has been realised that neither centre nor the state governments

have ever fulfilled their commitment of health spending. This has resulted in

inadequate provisions of health facility in the country, e.g., bed: population

ratio in India

is 1:1000 compared to the 7:1000 in developed nations. This has further

resulted in high (71%) out-of-pocket spending which is met out from

individual’s pocket.

health in India

is one of the lowest amongst the many developing countries and from the international

standard of spending. A low level of government spending on health sector seems

to be a generic problem in India.

The individual states were also unable to meet even the minimal level of

resource requirement for maintaining/ providing the basic health facility in

the country. It has been realised that neither centre nor the state governments

have ever fulfilled their commitment of health spending. This has resulted in

inadequate provisions of health facility in the country, e.g., bed: population

ratio in India

is 1:1000 compared to the 7:1000 in developed nations. This has further

resulted in high (71%) out-of-pocket spending which is met out from

individual’s pocket.

The expenditure on health however

shows little increasing trends especially after the implementation of NRHM in

2005. But spending level (1.2 per cent of GDP) recorded lower than the ambitious

commitments of increasing in the government health spending to 2-3 per cent of

GDP by the end of 11th plan. Under the mission, the central

government however has asked the state governments to increase their own

spending at a specified rate in tandem with the increased central funding. The

state governments however did not increase their spending at the required

level. Therefore, the transfer of central funds to state, which was based on

some conditionality, could not be utilized by the state governments adequately.

This is being reflected by the inadequate absorptive capacity of state

governments to utilize funds properly, which further result in slowing down the

NRHM implementation. Probably, lack of availability of human resources, weak

capacity to plan and their execution probably limits the state governments to

absorb the central fund adequately.

shows little increasing trends especially after the implementation of NRHM in

2005. But spending level (1.2 per cent of GDP) recorded lower than the ambitious

commitments of increasing in the government health spending to 2-3 per cent of

GDP by the end of 11th plan. Under the mission, the central

government however has asked the state governments to increase their own

spending at a specified rate in tandem with the increased central funding. The

state governments however did not increase their spending at the required

level. Therefore, the transfer of central funds to state, which was based on

some conditionality, could not be utilized by the state governments adequately.

This is being reflected by the inadequate absorptive capacity of state

governments to utilize funds properly, which further result in slowing down the

NRHM implementation. Probably, lack of availability of human resources, weak

capacity to plan and their execution probably limits the state governments to

absorb the central fund adequately.

Another feather of NRHM was to

transfer some of the central funds, which were earlier routed through state’s

budget (through Centrally Plan and Sponsored schemes-CPS/CSS) are now

transferred to states through state implementing agencies which bypass the

state’s budget. This changing route of central transfer has put limitations on

certain central sponsored health programmes running through CPS/CSS. It was

noticed that central transfer through CPS/CSS were declining which results in discontinuity of some of the

health programmes running in the villages like the pulse polio and national

disease control programmes. This bypassing nature of central transfer can

probably lead to disincentives to mobilize funds from state’s own exchequer. The

states might think that NRHM is a financial responsibility of central

government. Secondly, it is difficult to monitor the central funds passing

through state implementing agencies and see whether these funds have been

implemented effectively at the ground level. Further, with this changing route

of central transfer, the financial relationship between centre and state in a

federal structure becomes unnecessarily complex.

transfer some of the central funds, which were earlier routed through state’s

budget (through Centrally Plan and Sponsored schemes-CPS/CSS) are now

transferred to states through state implementing agencies which bypass the

state’s budget. This changing route of central transfer has put limitations on

certain central sponsored health programmes running through CPS/CSS. It was

noticed that central transfer through CPS/CSS were declining which results in discontinuity of some of the

health programmes running in the villages like the pulse polio and national

disease control programmes. This bypassing nature of central transfer can

probably lead to disincentives to mobilize funds from state’s own exchequer. The

states might think that NRHM is a financial responsibility of central

government. Secondly, it is difficult to monitor the central funds passing

through state implementing agencies and see whether these funds have been

implemented effectively at the ground level. Further, with this changing route

of central transfer, the financial relationship between centre and state in a

federal structure becomes unnecessarily complex.

The overall analysis confirms

that India

and its states are shying away from fulfilling its constitutional commitment of

‘Right to Health’ for its citizens. We observed that public health sector has

never been given adequate resources to perform well in India. Given

the low level, declining and fluctuating behaviour of health expenditure over

the last twenty five years, it is not surprising that the health sector

performance had not been satisfactory. The failing nature of better health

outcomes however can easily be reversed with increased allocation in this

sector. Specifically, India

needs to double or triple its health spending from its existing level. Along

with the commitments of health spending, it becomes important to ensure that

the allocated additional public funds get spent effectively across its

constituent states.

that India

and its states are shying away from fulfilling its constitutional commitment of

‘Right to Health’ for its citizens. We observed that public health sector has

never been given adequate resources to perform well in India. Given

the low level, declining and fluctuating behaviour of health expenditure over

the last twenty five years, it is not surprising that the health sector

performance had not been satisfactory. The failing nature of better health

outcomes however can easily be reversed with increased allocation in this

sector. Specifically, India

needs to double or triple its health spending from its existing level. Along

with the commitments of health spending, it becomes important to ensure that

the allocated additional public funds get spent effectively across its

constituent states.

The

author is Assistant Professor at the Institute for Studies in Industrial

Development, New Delhi.

author is Assistant Professor at the Institute for Studies in Industrial

Development, New Delhi.