Antara

Ray Chaudhury

Nationalism and the notion

of nation state has always been a matter of contestation and debate among the historians and

public intellectuals in India. Ironic at the outset, in post-globalisation

years (where nations and history were supposed to have met their end), the

concept and meaning of nationalism has come to dominate the public discourse

and has generated a novel ‘political’ around it with much vigour and force. The

issue of ‘tolerance’ and ‘intolerance’ which assumed serious proportions,

depth, meanings as a mobilising point of cultural, political forces and ideas

in 2015, was sought to be brandished as ‘anti-national’. The mockery of intolerance became the latest feed or a trending

topic in our social media. Nationalism

was now equated with faith in our ancient ‘advanced’

‘inherently tolerant’ ‘Vedic’ culture, and patriotism. The naysayers, doubters,

agnostics were retroactively committing heresy, blasphemy and treason by

uttering the mere innocuous liberal term

‘intolerance’. This identification of nation with culture and tradition has led

to what many fear as a threat to the ‘idea of India’. Thus it becomes important

to visit and revisit questions such as ‘what does it mean to be an Indian?

Whether there are some essential characteristics, a particular faith is

required to be practiced in order to be called as an Indian? And what are the

markers of being a nationalist?’ It is in this context the need to re-engage

with the concept of Nationalism arises.

of nation state has always been a matter of contestation and debate among the historians and

public intellectuals in India. Ironic at the outset, in post-globalisation

years (where nations and history were supposed to have met their end), the

concept and meaning of nationalism has come to dominate the public discourse

and has generated a novel ‘political’ around it with much vigour and force. The

issue of ‘tolerance’ and ‘intolerance’ which assumed serious proportions,

depth, meanings as a mobilising point of cultural, political forces and ideas

in 2015, was sought to be brandished as ‘anti-national’. The mockery of intolerance became the latest feed or a trending

topic in our social media. Nationalism

was now equated with faith in our ancient ‘advanced’

‘inherently tolerant’ ‘Vedic’ culture, and patriotism. The naysayers, doubters,

agnostics were retroactively committing heresy, blasphemy and treason by

uttering the mere innocuous liberal term

‘intolerance’. This identification of nation with culture and tradition has led

to what many fear as a threat to the ‘idea of India’. Thus it becomes important

to visit and revisit questions such as ‘what does it mean to be an Indian?

Whether there are some essential characteristics, a particular faith is

required to be practiced in order to be called as an Indian? And what are the

markers of being a nationalist?’ It is in this context the need to re-engage

with the concept of Nationalism arises.

Historians of different

schools of thought (Nationalist, Cambridge, Marxist, Subaltern) have given the

contours of the concept of nationalism and also their respective arguments

about the formation of Indian nation-state. Among all the disagreements there

is one aspect about which all these schools agree is the heterogeneity and

pluralism of the Indian society. However if one looks at the current

socio-political atmosphere in the country one cannot ignore the fact that, it

is the very plurality and heterogeneity of Indian society which is being

challenged and undermined in the name of nationalism.

schools of thought (Nationalist, Cambridge, Marxist, Subaltern) have given the

contours of the concept of nationalism and also their respective arguments

about the formation of Indian nation-state. Among all the disagreements there

is one aspect about which all these schools agree is the heterogeneity and

pluralism of the Indian society. However if one looks at the current

socio-political atmosphere in the country one cannot ignore the fact that, it

is the very plurality and heterogeneity of Indian society which is being

challenged and undermined in the name of nationalism.

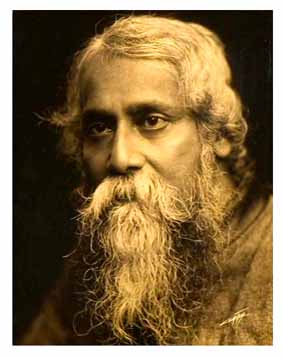

My aim in this article is

not to go back and revisit these debates among the different schools of

thoughts regarding Indian nationalism. Rather I have taken up the exercise of

revisiting one classic text written on Nationalism – Rabindranath Tagore’s ‘essays

on Nationalism’. It was one of his most political and controversial text

written at the height of the national movement and First World War. I have not

only tried to engage with the text critically but also tried to read it in the

current context. Thus the title of my article is Tagore’s Nationalism for

Our Times.

not to go back and revisit these debates among the different schools of

thoughts regarding Indian nationalism. Rather I have taken up the exercise of

revisiting one classic text written on Nationalism – Rabindranath Tagore’s ‘essays

on Nationalism’. It was one of his most political and controversial text

written at the height of the national movement and First World War. I have not

only tried to engage with the text critically but also tried to read it in the

current context. Thus the title of my article is Tagore’s Nationalism for

Our Times.

I.

Rabindranath Tagore’s essays on Nationalism is a compilation

of his lectures that he delivered in Japan and United States of America in

1916. It was first published by Macmillan, New York in 1917. The text contains

three essays Nationalism in the West, Nationalism in Japan & Nationalism

in India.

of his lectures that he delivered in Japan and United States of America in

1916. It was first published by Macmillan, New York in 1917. The text contains

three essays Nationalism in the West, Nationalism in Japan & Nationalism

in India.

Tagore was a poet first. Hence he follows

the maxim as E.P.Thompson noted in the introduction of 1991 edition of Nationalism

“never opt for a straight forward definition when a simile would suffice.” However,

in case of nation Tagore actually gives us a very clear definition of what he

meant by nation and from that his subsequent argument about nationalism that

(nationalism is a great menace)[1]

follows. Therefore discussion about Tagore’s view on nationalism should begin

with the question ‘what is Tagore’s concept of nation?’

the maxim as E.P.Thompson noted in the introduction of 1991 edition of Nationalism

“never opt for a straight forward definition when a simile would suffice.” However,

in case of nation Tagore actually gives us a very clear definition of what he

meant by nation and from that his subsequent argument about nationalism that

(nationalism is a great menace)[1]

follows. Therefore discussion about Tagore’s view on nationalism should begin

with the question ‘what is Tagore’s concept of nation?’

In the essay ‘nationalism in the West’ he

says that a nation is ‘that aspect which a whole population assumes when organised

for a mechanical purpose’[2]. It immediately looks like a distinctively

modern and exclusively western concept. Its mechanical purpose implicates an

instrumental rationality in its political organisational form. Therefore it

seems that for Tagore the nation is always the nation-state.

says that a nation is ‘that aspect which a whole population assumes when organised

for a mechanical purpose’[2]. It immediately looks like a distinctively

modern and exclusively western concept. Its mechanical purpose implicates an

instrumental rationality in its political organisational form. Therefore it

seems that for Tagore the nation is always the nation-state.

However what is interesting to note is

that this view of nation was markedly different from Tagore’s earlier view on the same. In two essays Nation ki?

(what is nation?) and Bharatbarshiya Samaj (Indian Society), published in 1901 he seems to

hold up the nation as an ideal which is worth striving for; in a nation the

selfish interest of the individual must give way to the welfare of the

inhabitants of the nation as a whole. A Nation, he says-“is a vital spirit, a

living entity” and he goes to the extent of saying that-“everyone in a nation

sacrifices his interest to protect the national interest.”

that this view of nation was markedly different from Tagore’s earlier view on the same. In two essays Nation ki?

(what is nation?) and Bharatbarshiya Samaj (Indian Society), published in 1901 he seems to

hold up the nation as an ideal which is worth striving for; in a nation the

selfish interest of the individual must give way to the welfare of the

inhabitants of the nation as a whole. A Nation, he says-“is a vital spirit, a

living entity” and he goes to the extent of saying that-“everyone in a nation

sacrifices his interest to protect the national interest.”

Tagore was heavily influenced at that

time by the writings of French Philosopher Ernest Renan. Shortly after this he

himself got involve with the Swadeshi movement in the aftermath of Partition of

Bengal in 1905. He was writing songs, giving speeches, taking part in mass

rallies. He also set up a match factory, a local bank, and a weaving centre as

his way of giving leadership to the movement. He was the one who set Bankim’s ‘वनदे मातरम’ (‘Vande Mataram’) as the movement’s theme song.

time by the writings of French Philosopher Ernest Renan. Shortly after this he

himself got involve with the Swadeshi movement in the aftermath of Partition of

Bengal in 1905. He was writing songs, giving speeches, taking part in mass

rallies. He also set up a match factory, a local bank, and a weaving centre as

his way of giving leadership to the movement. He was the one who set Bankim’s ‘वनदे मातरम’ (‘Vande Mataram’) as the movement’s theme song.

One thing to be noted here is the absence

of mechanical, coercive notion of the nation that we found in his later

writings. The first indication of his disillusionment with the idea of nation

can be found in his essay ‘Sadupay’ (The Right Means) published in 1908

where he clearly stated his reasons for rejecting the swadeshi militant

nationalism. Citing the examples of poor Muslims and low caste Hindu peasants;

he criticised the way in which elite leaders of the movement forced the boycott

of British-made goods to the downtrodden. Tagore vehemently criticised the use

of force by the elites to get the poor peasants for their agenda. In the essay

Sadupay we can see Tagore inching towards his later opinion about the

nation as a terrible absurdity organised for a mechanical purpose. Historian

Sumit Sarkar has noted that “it is this notion of freedom, or individual human

rights, affirmed, if needed against community disciplines, that lay at the

heart of Tagore’s more general criticism of nationalism”[3]

of mechanical, coercive notion of the nation that we found in his later

writings. The first indication of his disillusionment with the idea of nation

can be found in his essay ‘Sadupay’ (The Right Means) published in 1908

where he clearly stated his reasons for rejecting the swadeshi militant

nationalism. Citing the examples of poor Muslims and low caste Hindu peasants;

he criticised the way in which elite leaders of the movement forced the boycott

of British-made goods to the downtrodden. Tagore vehemently criticised the use

of force by the elites to get the poor peasants for their agenda. In the essay

Sadupay we can see Tagore inching towards his later opinion about the

nation as a terrible absurdity organised for a mechanical purpose. Historian

Sumit Sarkar has noted that “it is this notion of freedom, or individual human

rights, affirmed, if needed against community disciplines, that lay at the

heart of Tagore’s more general criticism of nationalism”[3]

A more subtle and nuanced analyses of

nationalism can be found in two of his most celebrated novels ‘Gora’ (written

in 1909) and ‘Ghare Baire‘ (1915) which needs a brief discussion.

nationalism can be found in two of his most celebrated novels ‘Gora’ (written

in 1909) and ‘Ghare Baire‘ (1915) which needs a brief discussion.

The novel ‘Gora’ was one of the

first literary expression of new political turn which deepen over time. It was

one of the first novels that Tagore wrote on modern domestic, political and

social situations after ‘ChokherBali’ and ‘Noukadubi’. Gora who knew himself as a Hindu Brahmin wants

to build a Hindu India. But later on he came to know that he was Christian and

Irish by birth and was brought by a Hindu family and faces an intense crisis of

identity. At the end of the novel he undergoes a spiritual transformation and realises

the need to transcend narrow religious identities. He tells Paresh Babu that

today give me the mantra of that Deity who belongs to all. Later he goes to his

foster mother Anandamayee and falls at her feet and tells her “mother, you are

that mother of mine, I searched for her everywhere and all the while she sat at

home, waiting for me…..you have no caste, no hatred, no laws, you are the image

of love. You are my Bharatvarsha.” These last few lines of the novel therefore

become extremely crucial to understand Tagore’s Idea of India.

first literary expression of new political turn which deepen over time. It was

one of the first novels that Tagore wrote on modern domestic, political and

social situations after ‘ChokherBali’ and ‘Noukadubi’. Gora who knew himself as a Hindu Brahmin wants

to build a Hindu India. But later on he came to know that he was Christian and

Irish by birth and was brought by a Hindu family and faces an intense crisis of

identity. At the end of the novel he undergoes a spiritual transformation and realises

the need to transcend narrow religious identities. He tells Paresh Babu that

today give me the mantra of that Deity who belongs to all. Later he goes to his

foster mother Anandamayee and falls at her feet and tells her “mother, you are

that mother of mine, I searched for her everywhere and all the while she sat at

home, waiting for me…..you have no caste, no hatred, no laws, you are the image

of love. You are my Bharatvarsha.” These last few lines of the novel therefore

become extremely crucial to understand Tagore’s Idea of India.

‘Ghare Baire‘ (1915) set

against the backdrop of the Swadeshi movement in Bengal was another novel where

Tagore has launched his fiercest attack against the ideology of communal notion

of nationalism. The novel deals with experiences of 3 characters Nikhil a benevolent progressive zamindar, his

childhood friend charismatic nationalist leader Sandip and Nikhil’s wife Bimala. With the help of this three

characters Tagore wanted to portray the condition of Bengal tottering between

the two possibilities where Nikhil is

for humanitarian global perspective based on true equality and harmony

between individuals and Sandip is for radical Hindu nationalism which threaten to replace moral sensibility

with national bigotry and blind fanaticism. The death of Nikhil in the end of

the novel when Bimala was returning to her senses after a prolonged infatuation

with Sandip and his views also signals Tagore’s note of caution about the future of Bengal.

against the backdrop of the Swadeshi movement in Bengal was another novel where

Tagore has launched his fiercest attack against the ideology of communal notion

of nationalism. The novel deals with experiences of 3 characters Nikhil a benevolent progressive zamindar, his

childhood friend charismatic nationalist leader Sandip and Nikhil’s wife Bimala. With the help of this three

characters Tagore wanted to portray the condition of Bengal tottering between

the two possibilities where Nikhil is

for humanitarian global perspective based on true equality and harmony

between individuals and Sandip is for radical Hindu nationalism which threaten to replace moral sensibility

with national bigotry and blind fanaticism. The death of Nikhil in the end of

the novel when Bimala was returning to her senses after a prolonged infatuation

with Sandip and his views also signals Tagore’s note of caution about the future of Bengal.

These novels are extremely important in

another sense in their postulation of Hindu revivalism as a modern political

movement which deployed fantasy as core element, and its ideological defeat

only possible through certain ‘trauma’ where the subject held under bad faith

is finally able to see through the lie.

another sense in their postulation of Hindu revivalism as a modern political

movement which deployed fantasy as core element, and its ideological defeat

only possible through certain ‘trauma’ where the subject held under bad faith

is finally able to see through the lie.

II.

These writings set the stage for his

views on nationalism. In the first essay Nationalism in the West, Tagore

begins his critique of nationalism by stating-“in the West the national

machinery of commerce and politics turns out neatly compressed bales of

humanity which have their use and high market value; but they are bound in iron

hoops, labeled and separated off with scientific care and precision’[4]. From here he goes on to ask the question ‘what

is this nation?’ and as I mentioned earlier he gives the

following clear definition ‘a nation is that aspect of which a whole population

assumes when organised for a mechanical purpose’ and a little later he states ‘nation is the

organisation of politics and commerce’[5]. He further goes on to explain why this western

concept of nation and nationalism which

is not only mechanical but also not suitable for a country like India.

views on nationalism. In the first essay Nationalism in the West, Tagore

begins his critique of nationalism by stating-“in the West the national

machinery of commerce and politics turns out neatly compressed bales of

humanity which have their use and high market value; but they are bound in iron

hoops, labeled and separated off with scientific care and precision’[4]. From here he goes on to ask the question ‘what

is this nation?’ and as I mentioned earlier he gives the

following clear definition ‘a nation is that aspect of which a whole population

assumes when organised for a mechanical purpose’ and a little later he states ‘nation is the

organisation of politics and commerce’[5]. He further goes on to explain why this western

concept of nation and nationalism which

is not only mechanical but also not suitable for a country like India.

He says-“neither the vagueness of

colourless cosmopolitanism nor the force self idolatry of nation worship is the

goal of human history. India has been trying to accomplish her task through social regulation of difference in

one hand and spiritual unity on the other. He compares India with the hostess

who is trying to give proper accommodation to her numerous guests whose habits

and requirements are different from each other. So the true realisation of the

unity of man can help in achieving this. The history of India was not just a

mere history of conquest for political supremacy and aggression on the other

hand; her thrones were not her concern, they passed over her head like clouds,

often they brought devastation but it was soon forgotten like a catastrophe of

nature.” However with the coming of imperial power it should be borne in mind

that this time the machinery of the West was digging deep into our soil. This

time it was not the human race of Mughals and Pathans it was the nation of

England that we had to encounter. Tagore looks the imperial invasion as a major

break in the history of India. History of India does not belong to any

particular race. India which is ‘devoid of all politics ,the India of no nations’[6], the nation of the West burst in with the rule

of the British.

colourless cosmopolitanism nor the force self idolatry of nation worship is the

goal of human history. India has been trying to accomplish her task through social regulation of difference in

one hand and spiritual unity on the other. He compares India with the hostess

who is trying to give proper accommodation to her numerous guests whose habits

and requirements are different from each other. So the true realisation of the

unity of man can help in achieving this. The history of India was not just a

mere history of conquest for political supremacy and aggression on the other

hand; her thrones were not her concern, they passed over her head like clouds,

often they brought devastation but it was soon forgotten like a catastrophe of

nature.” However with the coming of imperial power it should be borne in mind

that this time the machinery of the West was digging deep into our soil. This

time it was not the human race of Mughals and Pathans it was the nation of

England that we had to encounter. Tagore looks the imperial invasion as a major

break in the history of India. History of India does not belong to any

particular race. India which is ‘devoid of all politics ,the India of no nations’[6], the nation of the West burst in with the rule

of the British.

This western concept of nation therefore

varies distinctly from what we had before the British came-“it is like the

difference between hand loom and power loom”. It is mechanical, monotonous

and devoid of human touch. Tagore however makes a clear distinction between the

spirit of the West and the nation of the West. He says that idea of universal

justice which represents the spirit of the West, which has free flowing ideas

of freedom, rationality has been guarded by or obstructed by the machinery of

nation which works as a Dam. This dehumanising tendency works like an apparatus

which has been christened as ‘Nation’ in the West. Thus this nation is a modern

western construct made up of power and greed and an imposition on us.

varies distinctly from what we had before the British came-“it is like the

difference between hand loom and power loom”. It is mechanical, monotonous

and devoid of human touch. Tagore however makes a clear distinction between the

spirit of the West and the nation of the West. He says that idea of universal

justice which represents the spirit of the West, which has free flowing ideas

of freedom, rationality has been guarded by or obstructed by the machinery of

nation which works as a Dam. This dehumanising tendency works like an apparatus

which has been christened as ‘Nation’ in the West. Thus this nation is a modern

western construct made up of power and greed and an imposition on us.

In the second essay nationalism in Japan

Tagore’s argument against nationalism becomes further

nuanced. He begins this essay by citing the larger picture of Asia which

according to the West lives in the past. We are made to believe that there is

something inherent in the soil and climate of Asia that produces mental

inactivity and atrophy. However Japan has proven the West wrong and she has not

done it by merely imitating the West. Tagore makes a distinction about what the

West has presented before us and what could be the offer from the East to that.

If the West has given us conflict between individual and the state, labour and

capital, man and woman, material gain and spiritual gain, organised selfishness

of the nation and higher levels of humanity then the eastern mind can offer

spiritual strength, love of simplicity, recognition of social obligation in

order to cut a new path for this great unwidely car of progress. If genius of

Europe has given her people power of organisation then genius of Japan here in

particular can give vision of beauty in nature and the power of realising it.

Because the ideal of ‘maitri’ is the foundation of her culture-maitri

with men and with nature. Tagore firmly believes that Japan has so much to

offer as an alternative to the western nationalism therefore he warns Japan not

to accept the motive force of the western nationalism as her own and asks the land of the rising sun to lead Asia and

to be missionary of the East to illuminate the whole world.

Tagore’s argument against nationalism becomes further

nuanced. He begins this essay by citing the larger picture of Asia which

according to the West lives in the past. We are made to believe that there is

something inherent in the soil and climate of Asia that produces mental

inactivity and atrophy. However Japan has proven the West wrong and she has not

done it by merely imitating the West. Tagore makes a distinction about what the

West has presented before us and what could be the offer from the East to that.

If the West has given us conflict between individual and the state, labour and

capital, man and woman, material gain and spiritual gain, organised selfishness

of the nation and higher levels of humanity then the eastern mind can offer

spiritual strength, love of simplicity, recognition of social obligation in

order to cut a new path for this great unwidely car of progress. If genius of

Europe has given her people power of organisation then genius of Japan here in

particular can give vision of beauty in nature and the power of realising it.

Because the ideal of ‘maitri’ is the foundation of her culture-maitri

with men and with nature. Tagore firmly believes that Japan has so much to

offer as an alternative to the western nationalism therefore he warns Japan not

to accept the motive force of the western nationalism as her own and asks the land of the rising sun to lead Asia and

to be missionary of the East to illuminate the whole world.

Finally when we come to the last and

final essay of the text Nationalism in India he begins by locating the

real problem of India in the social sphere and makes the point that India’s main problem is the problem of ‘race’. Here Tagore has made some interesting remarks

about the caste system and its management in India as he thinks this

heterogeneity and diversity caused by the caste system actually is the outcome

of the ‘spirit of toleration’ because ‘India tolerated difference of

races from the very beginning and that spirit of toleration has acted through

her history’ .

final essay of the text Nationalism in India he begins by locating the

real problem of India in the social sphere and makes the point that India’s main problem is the problem of ‘race’. Here Tagore has made some interesting remarks

about the caste system and its management in India as he thinks this

heterogeneity and diversity caused by the caste system actually is the outcome

of the ‘spirit of toleration’ because ‘India tolerated difference of

races from the very beginning and that spirit of toleration has acted through

her history’ .

However it will be a misconception to

think that Tagore supported the caste hierarchies because in this essay and in

various other writings he had vehemently criticised this as by saying ‘in her

caste regulation India has recognised differences but not the mutability which

is the law of life’[7]. And therefore he draws a parallel between

America and India as both are dealing with diversity of races and also tells

America to solve its race problem before pointing finger towards India. Here

Tagore comes back to his main argument of the text and says-“India never had a

homogeneity in terms of race. India has never had a real sense of nationalism.

Even though from childhood I had been taught that the idolatry of nation is

almost better than reverence for God and humanity, I believe I have outgrown

that teaching and it is my conviction that my country men will gain truly their

India by fighting against that education which teaches them that a country is

greater than the ideals of humanity,…I am not only against one nation in

particular but against the general idea of all nations’ and ‘nationalism is a great menace; it is the

particular thing which for years has been at the bottom of India’s trouble’[8].

think that Tagore supported the caste hierarchies because in this essay and in

various other writings he had vehemently criticised this as by saying ‘in her

caste regulation India has recognised differences but not the mutability which

is the law of life’[7]. And therefore he draws a parallel between

America and India as both are dealing with diversity of races and also tells

America to solve its race problem before pointing finger towards India. Here

Tagore comes back to his main argument of the text and says-“India never had a

homogeneity in terms of race. India has never had a real sense of nationalism.

Even though from childhood I had been taught that the idolatry of nation is

almost better than reverence for God and humanity, I believe I have outgrown

that teaching and it is my conviction that my country men will gain truly their

India by fighting against that education which teaches them that a country is

greater than the ideals of humanity,…I am not only against one nation in

particular but against the general idea of all nations’ and ‘nationalism is a great menace; it is the

particular thing which for years has been at the bottom of India’s trouble’[8].

III.

Communalism and political

Hindutva as the homogenising venture is as old as emergence of modern

anti-colonial Indian nationalism itself. They share a complex, problematic and

troubled history. The uneven nature of development of capitalism in India, its communal

foundations, and incomplete transformation of feudalism in economy and ideology

have shaped the contours of both anti-colonial nationalism as well as

communalism. Thus, it is critical to recognise and view the ‘modern’ basis and ‘modernising’

character of Hindutva as compared to traditional conservatism. Political

Hindutva’s primary aim remains capturing the state. It restructures the

conservative beliefs, fetishises them into symbols of mobilisation (from ‘Bharatmata’

to ‘Ram Mandir’), and cleverly supplants

the popular mobilisations and sentiments of anti-colonialism with a communal

twist through the mythical narrative of ‘fall’ from ‘golden age’. It drives a

wedge through body politic where possibilities of class struggle are closed in

favour of what Zizek has called as ‘ultra-politics’ to safeguard the existing

property relations. This ultra-politics is ‘the attempt to depoliticise the

conflict by bringing it to an extreme via the direct militarisation of

politics-by reformulating it as the war between ‘us’ and ‘them’, our

enemy’[9].

Hindutva as the homogenising venture is as old as emergence of modern

anti-colonial Indian nationalism itself. They share a complex, problematic and

troubled history. The uneven nature of development of capitalism in India, its communal

foundations, and incomplete transformation of feudalism in economy and ideology

have shaped the contours of both anti-colonial nationalism as well as

communalism. Thus, it is critical to recognise and view the ‘modern’ basis and ‘modernising’

character of Hindutva as compared to traditional conservatism. Political

Hindutva’s primary aim remains capturing the state. It restructures the

conservative beliefs, fetishises them into symbols of mobilisation (from ‘Bharatmata’

to ‘Ram Mandir’), and cleverly supplants

the popular mobilisations and sentiments of anti-colonialism with a communal

twist through the mythical narrative of ‘fall’ from ‘golden age’. It drives a

wedge through body politic where possibilities of class struggle are closed in

favour of what Zizek has called as ‘ultra-politics’ to safeguard the existing

property relations. This ultra-politics is ‘the attempt to depoliticise the

conflict by bringing it to an extreme via the direct militarisation of

politics-by reformulating it as the war between ‘us’ and ‘them’, our

enemy’[9].

Like many others of the

day, Rabindranath Tagore was also initially influenced by revivalist tendencies

sustaining a communal vocabulary popular during the times of partition of

Bengal. However, he was among the first to recognise this as a ‘modern’ development,

the dangers of communal project and what it would mean for the Indian

nationalism, Indian nation and its people. His is an interesting journey from

his praise of Bankim’s revivalism to later day internationalism & humanism

informed by modernist faith in science, and universalism, and offers valuable

insights into our own engagement with categories of nation and politics around

it.

day, Rabindranath Tagore was also initially influenced by revivalist tendencies

sustaining a communal vocabulary popular during the times of partition of

Bengal. However, he was among the first to recognise this as a ‘modern’ development,

the dangers of communal project and what it would mean for the Indian

nationalism, Indian nation and its people. His is an interesting journey from

his praise of Bankim’s revivalism to later day internationalism & humanism

informed by modernist faith in science, and universalism, and offers valuable

insights into our own engagement with categories of nation and politics around

it.

Let me conclude from where

we began – discussion on tolerance and what it means to nation. This is what

Tagore had to say about heterodoxy and its criticality to life, let alone

nation:

we began – discussion on tolerance and what it means to nation. This is what

Tagore had to say about heterodoxy and its criticality to life, let alone

nation:

“If a man tells me he has

heterodox ideas, but that he cannot follow them because he would be socially

ostracised, I excuse him for having to live a life of untruth, in order to live

at all.

heterodox ideas, but that he cannot follow them because he would be socially

ostracised, I excuse him for having to live a life of untruth, in order to live

at all.

The social habit of mind

which impels us to make the life of our fellow-beings a burden to them where

they differ from us even in such a thing as their choice of food is sure to

persist in our political organisation and result in creating engines of

coercion to crush every rational difference which is the sign of life. And

tyranny will only add to the inevitable lies and hypocrisy in our political

life”[10].

which impels us to make the life of our fellow-beings a burden to them where

they differ from us even in such a thing as their choice of food is sure to

persist in our political organisation and result in creating engines of

coercion to crush every rational difference which is the sign of life. And

tyranny will only add to the inevitable lies and hypocrisy in our political

life”[10].