S.V. Narayanan

All

social institutions that we created and experiencing operate within a

particular political environment. The values and ethics associated with these

institutions are to a larger extent being shaped and disciplined by the larger

socio-economic context in which they function. This structural relation and its

understanding will help us in critically evaluating the purpose and functioning

of these institutions. Law, being a socio-legal institution, which is identified

as objective and scientific, also operates within this larger political

context, carrying and reflecting its values and influences. Indian legal system

operates within the class and caste ridden society, which influences its

interpretation and judgement, by reinforcing the societal values over and above

the objectivity and scientific nature of legal studies. This paper will

critically evaluate the important interpretations made in three important legal

cases in India, which is significant in reflecting our regressive social values

in the higher legal institutions; The Kizhvenmani massacre in 1968 in Tamilnadu

where 44 dalits were burned alive, the Ayodhya judgement in 1986 which opened

the gates of communal politics at the national level and Bhanwari Devi case judgement in 1995 which combined

casteism and patriarchy in its interpretations. The underlying assumptions

behind the judgement and the social values associated with them will be

critically analysed rather than dwelling deep into the judgement and its legal

merits.

social institutions that we created and experiencing operate within a

particular political environment. The values and ethics associated with these

institutions are to a larger extent being shaped and disciplined by the larger

socio-economic context in which they function. This structural relation and its

understanding will help us in critically evaluating the purpose and functioning

of these institutions. Law, being a socio-legal institution, which is identified

as objective and scientific, also operates within this larger political

context, carrying and reflecting its values and influences. Indian legal system

operates within the class and caste ridden society, which influences its

interpretation and judgement, by reinforcing the societal values over and above

the objectivity and scientific nature of legal studies. This paper will

critically evaluate the important interpretations made in three important legal

cases in India, which is significant in reflecting our regressive social values

in the higher legal institutions; The Kizhvenmani massacre in 1968 in Tamilnadu

where 44 dalits were burned alive, the Ayodhya judgement in 1986 which opened

the gates of communal politics at the national level and Bhanwari Devi case judgement in 1995 which combined

casteism and patriarchy in its interpretations. The underlying assumptions

behind the judgement and the social values associated with them will be

critically analysed rather than dwelling deep into the judgement and its legal

merits.

Law and

Politics

Politics

The

legal institution’s rules and decisions cannot be comprehended convincingly, if

we look it independently without locating it in a larger social context. Since

law is embedded within the society and it reflects and influences the culture

in which it operates, the legal institutional functioning can be understood

properly by situating it within society and its nature (Mather, 2008). The societal values and understanding, influences

the decisions of legal institutions, as the individual decision makers or

judges are part of this societal conglomeration. According to Cerar (2009), the

law could be a goal, a means or an obstacle in relation to politics. The

politics can identify certain legal values as its goal, the law could be used

as means for achieving certain political interests or it could be identified as

an obstacle while achieving certain political goals. Thus, the legal

institutions and its values are strongly intertwined with the political context

in which it operates.

legal institution’s rules and decisions cannot be comprehended convincingly, if

we look it independently without locating it in a larger social context. Since

law is embedded within the society and it reflects and influences the culture

in which it operates, the legal institutional functioning can be understood

properly by situating it within society and its nature (Mather, 2008). The societal values and understanding, influences

the decisions of legal institutions, as the individual decision makers or

judges are part of this societal conglomeration. According to Cerar (2009), the

law could be a goal, a means or an obstacle in relation to politics. The

politics can identify certain legal values as its goal, the law could be used

as means for achieving certain political interests or it could be identified as

an obstacle while achieving certain political goals. Thus, the legal

institutions and its values are strongly intertwined with the political context

in which it operates.

Even

though Marx and Engels did not write in detail about the place and function of

law and its institutions, their analysis of 1834 Poor Law Amendment and Corn

Laws, has given certain direction for the Marxian politics to develop the

concept further. They considered law, similar to politics (Liberal Democracy), as

a tool which was used to cover up the capitalist exploitation. Law also

transforms itself according to the changes in the economic sphere to strengthen

the exploitative apparatus within the capitalist political economy (Stone,

1985). Thus, the legal institutions are consistent in not only protecting

property rights, but also in protecting the property owners, who forms the

basic foundation of capitalism.

though Marx and Engels did not write in detail about the place and function of

law and its institutions, their analysis of 1834 Poor Law Amendment and Corn

Laws, has given certain direction for the Marxian politics to develop the

concept further. They considered law, similar to politics (Liberal Democracy), as

a tool which was used to cover up the capitalist exploitation. Law also

transforms itself according to the changes in the economic sphere to strengthen

the exploitative apparatus within the capitalist political economy (Stone,

1985). Thus, the legal institutions are consistent in not only protecting

property rights, but also in protecting the property owners, who forms the

basic foundation of capitalism.

Within

the study of the relationship between law and society, the decision-making

process in courts is one of the important area which tries to understand the

socio-economic structure and its influence in the judicial process and its

outcome. Class, race, caste, gender and other forms of discrimination gets

reflected in the judicial judgements, which is nothing but the reflection of

our societal values and practices. The economic structure, cultural values and

other forms of societal influences forms the context in which the court

judgements needs to understood (Mather, 2008).

Thus, from the above discussion we understand that the economic structure and

shared cultural values in a society does have an strong influence over the

judicial decisions in the court of law. From this understanding, we will try to

look critically, how such societal condition and values have influenced the

judgement in Kizhvenmani, Ayodhya and Bhanwari Devi case

judgements. We will try to glean the important observations of the

judges in these cases, rather than complete analysis of the judgement, to

understand the values that influenced the decision-making process.

the study of the relationship between law and society, the decision-making

process in courts is one of the important area which tries to understand the

socio-economic structure and its influence in the judicial process and its

outcome. Class, race, caste, gender and other forms of discrimination gets

reflected in the judicial judgements, which is nothing but the reflection of

our societal values and practices. The economic structure, cultural values and

other forms of societal influences forms the context in which the court

judgements needs to understood (Mather, 2008).

Thus, from the above discussion we understand that the economic structure and

shared cultural values in a society does have an strong influence over the

judicial decisions in the court of law. From this understanding, we will try to

look critically, how such societal condition and values have influenced the

judgement in Kizhvenmani, Ayodhya and Bhanwari Devi case

judgements. We will try to glean the important observations of the

judges in these cases, rather than complete analysis of the judgement, to

understand the values that influenced the decision-making process.

Politicized

Legal Interpretations

Legal Interpretations

In this

section, we will critically look at the three important judgements, in

independent India,

to understand its rationale and context.

section, we will critically look at the three important judgements, in

independent India,

to understand its rationale and context.

Kizhvenmani

Case

Case

Kizhvenmani,

a remote village of erstwhile Thanjavur in Tamilnadu came to highlight in 1968,

when 44 dalit agricultural labourers ( Mostly women and their children) were

burnt alive, by landlords, for

protesting and demanding higher wages. Thanjavur, was a fertile region in

1960’s with generous rice and paddy production making it agriculturally rich

area. But the land ownership was dominated by few rich landlords, who

controlled and oppressed the majority of lower caste landless agricultural

labourers. According to EPW (1973; 927),

a remote village of erstwhile Thanjavur in Tamilnadu came to highlight in 1968,

when 44 dalit agricultural labourers ( Mostly women and their children) were

burnt alive, by landlords, for

protesting and demanding higher wages. Thanjavur, was a fertile region in

1960’s with generous rice and paddy production making it agriculturally rich

area. But the land ownership was dominated by few rich landlords, who

controlled and oppressed the majority of lower caste landless agricultural

labourers. According to EPW (1973; 927),

” In

1961, 3.8 per cent of the cultivating households, owning more than 15 acres

each, held 25.88 per cent of the cultivated area, while 76 per cent, owning up

to 5 acres each, held only 37 per cent of the area. Thanjavur also has the

highest proportion of landless labourers: for every 10 cultivators, there were

9 labourers in 1961. The 1971 Census found 41 per cent of the rural population

to be landless labour while the state average was 29 per cent. Thanjavur also

has the highest percent-age of Harijans (Dalits) among the

landless. A combination of these factors had made Thanjavur a classic

setting for feudal oppression. It was here that feudal serfdom had fully

developed. A pannaiyal (attached labourer) pledged the services of

himself, his wife and their children to be born to the landlord until the loan,

usually taken for marriage, of about Rs 50 was fully recovered. Considering the

pittance of a wage that he received, the recovery of the loan not unusually

took longer than the life of the pannaiyal“.

1961, 3.8 per cent of the cultivating households, owning more than 15 acres

each, held 25.88 per cent of the cultivated area, while 76 per cent, owning up

to 5 acres each, held only 37 per cent of the area. Thanjavur also has the

highest proportion of landless labourers: for every 10 cultivators, there were

9 labourers in 1961. The 1971 Census found 41 per cent of the rural population

to be landless labour while the state average was 29 per cent. Thanjavur also

has the highest percent-age of Harijans (Dalits) among the

landless. A combination of these factors had made Thanjavur a classic

setting for feudal oppression. It was here that feudal serfdom had fully

developed. A pannaiyal (attached labourer) pledged the services of

himself, his wife and their children to be born to the landlord until the loan,

usually taken for marriage, of about Rs 50 was fully recovered. Considering the

pittance of a wage that he received, the recovery of the loan not unusually

took longer than the life of the pannaiyal“.

The

green revolution, in effect had increased the agricultural production and the

prices during 1960’s, which made the dalit labourers, organised under communist

party, to demand higher wages from the landlord (Gough, 1976). The dalit

labourers demand of half a litre more of rice as wages has been stoutly

resisted by Paddy Producers Association ( PPA) under the leadership of

Mr.Gopalakrishna Naidu, the president of PPA. These landlords brought labourers

from outside the village, which infuriated the local labourers and culminated

into a conflict where one Mr.Pakkirisamy Pillai, from landlord side, was killed

in the clash. In response to this, the landlords organised themselves and

attacked the Kizhvenmani village, shooting the labourers and finally burning

down 44 dalits (Viswanathan, 2006). But, the killing of Mr.Pakkirisamy was only

a trigger, the real reason lies behind the class and caste based accumulated

anger, where the landlords were not able to digest the dalit labourers uprising

against them and questioning their authority, which was unassailable for many

centuries due to caste and class oppression. This is very apparent in the conversation

by a landlord with the EPW(1973; 926 – 927) author,

green revolution, in effect had increased the agricultural production and the

prices during 1960’s, which made the dalit labourers, organised under communist

party, to demand higher wages from the landlord (Gough, 1976). The dalit

labourers demand of half a litre more of rice as wages has been stoutly

resisted by Paddy Producers Association ( PPA) under the leadership of

Mr.Gopalakrishna Naidu, the president of PPA. These landlords brought labourers

from outside the village, which infuriated the local labourers and culminated

into a conflict where one Mr.Pakkirisamy Pillai, from landlord side, was killed

in the clash. In response to this, the landlords organised themselves and

attacked the Kizhvenmani village, shooting the labourers and finally burning

down 44 dalits (Viswanathan, 2006). But, the killing of Mr.Pakkirisamy was only

a trigger, the real reason lies behind the class and caste based accumulated

anger, where the landlords were not able to digest the dalit labourers uprising

against them and questioning their authority, which was unassailable for many

centuries due to caste and class oppression. This is very apparent in the conversation

by a landlord with the EPW(1973; 926 – 927) author,

“Things used to be

very peaceful here some

years

ago. The labourers were very hard-working and respectful. But now . . . the

fellow who used to stand in the backyard of my house to talk to me comes

straight to the verandah wearing slippers and all. At 5.30 pm sharp he says,

‘Our leader is speaking today at a public meeting. I have to go’. His leader

holds a meeting right next door to me and parades the streets with the red

flag. These fellows have become lazy and arrogant, thanks to the Communists.

They have no fear in them anymore.”

very peaceful here some

years

ago. The labourers were very hard-working and respectful. But now . . . the

fellow who used to stand in the backyard of my house to talk to me comes

straight to the verandah wearing slippers and all. At 5.30 pm sharp he says,

‘Our leader is speaking today at a public meeting. I have to go’. His leader

holds a meeting right next door to me and parades the streets with the red

flag. These fellows have become lazy and arrogant, thanks to the Communists.

They have no fear in them anymore.”

The common perception

that prevailed in this period reflects the century old caste and class based

discipline and behaviour, which was the main basis for exploiting the labour of

lower-caste people. The landlords should be treated with respect, they cannot

be questioned, they cannot be wrong, their words are final and whoever opposes

these rules, the landlords have the inherent right to punish the violators. The

caste position also gave the landlords complete freedom to punish the

perpetuators, where the Manusmriti, the Hindu religious code, gives

punishment based on the caste position, favouring the upper caste. These

perception were reflected in the court judgement, where all the landlords, who

burnt and killed 44 dalit labourers were let free, but the dalit labourers, who

was indicted in killing Mr.Pakkirisamy was punished.

that prevailed in this period reflects the century old caste and class based

discipline and behaviour, which was the main basis for exploiting the labour of

lower-caste people. The landlords should be treated with respect, they cannot

be questioned, they cannot be wrong, their words are final and whoever opposes

these rules, the landlords have the inherent right to punish the violators. The

caste position also gave the landlords complete freedom to punish the

perpetuators, where the Manusmriti, the Hindu religious code, gives

punishment based on the caste position, favouring the upper caste. These

perception were reflected in the court judgement, where all the landlords, who

burnt and killed 44 dalit labourers were let free, but the dalit labourers, who

was indicted in killing Mr.Pakkirisamy was punished.

In

Mr.Pakkirisamy murder case, out of the eight accused, one was given life

sentence and others were given rigorous imprisonment, where the Nagai sessions

court agreed that the attack against him was not a planned attack. But, the

sessions court considered the killing of 44 dalit labourers as a preconceived

and deliberate attack and sentenced the accused to 10 years of rigorous

imprisonment. When both of them went to Madras High Court, the punishment for

the labourers were upheld and the punishment for the landlords were quashed (Kanagasabai, 2014). More than the judgment,

the observations of the Madras High Court judges in this case regarding the

landlords and their involvement in killing of 44 dalit labourers was more

shocking and reflecting the common perception of people in a caste and class

divided society. The judgement was delivered by Mr.Venkataraman and

Mr.Maharajan on April 6th 1973, in the criminal appeal no: 1208/1970 and 593/1971. The judges observed in their

ruling,

Mr.Pakkirisamy murder case, out of the eight accused, one was given life

sentence and others were given rigorous imprisonment, where the Nagai sessions

court agreed that the attack against him was not a planned attack. But, the

sessions court considered the killing of 44 dalit labourers as a preconceived

and deliberate attack and sentenced the accused to 10 years of rigorous

imprisonment. When both of them went to Madras High Court, the punishment for

the labourers were upheld and the punishment for the landlords were quashed (Kanagasabai, 2014). More than the judgment,

the observations of the Madras High Court judges in this case regarding the

landlords and their involvement in killing of 44 dalit labourers was more

shocking and reflecting the common perception of people in a caste and class

divided society. The judgement was delivered by Mr.Venkataraman and

Mr.Maharajan on April 6th 1973, in the criminal appeal no: 1208/1970 and 593/1971. The judges observed in their

ruling,

“…

there was something astonishing about the fact that all the 23 persons

implicated in the case should be mirasdars. Most of them were rich men, owning

vast extent of lands and Gopala Krishna Naidu

possessed a car. However much they might have been eager to wreak vengeance on

the kisans, it was difficult to believe that they would walk bodily to the

scene and set fire to the houses, unaided by any of their servants. They were

more likely to play safe, unlike desperate hungry labourers. One would rather

expect that the mirasdars, keeping themselves in the background would, send

their servants to commit the several offences which according to the

prosecution the mirasdars personally committed… The evidence did not enable

their lordships to identify and punish the guilty”(Balu,

2009; 435).

there was something astonishing about the fact that all the 23 persons

implicated in the case should be mirasdars. Most of them were rich men, owning

vast extent of lands and Gopala Krishna Naidu

possessed a car. However much they might have been eager to wreak vengeance on

the kisans, it was difficult to believe that they would walk bodily to the

scene and set fire to the houses, unaided by any of their servants. They were

more likely to play safe, unlike desperate hungry labourers. One would rather

expect that the mirasdars, keeping themselves in the background would, send

their servants to commit the several offences which according to the

prosecution the mirasdars personally committed… The evidence did not enable

their lordships to identify and punish the guilty”(Balu,

2009; 435).

Further,

the court held that the people who kept fire for the house are unaware that 44

people were inside and they had no intension to kill them. Are they so innocent

to not hear scream or lock a hut which is empty without any human being inside?

Based on certain frivolous interpretation of the evidences, the judges have

decided that the workers and communist leaders conspired to trap Gopala Krishna

Naidu in the case. The Supreme court also upheld this decision to set free the

landlords. The judges observation clearly accepted the caste position and

economic status of the landlords, and made this as basis to clear them of any

criminal intension. The land and cars owned by the landlords not only made them

superior, but also excluded them from involving in the cheap and direct act of

killing labourers. The judgement implies that only desperate hungry labourer (

lower caste) are capable of doing such stupid things and landlords being

economically wealthy ( upper caste) will not even enter the lower caste

dwellings and they are smart enough to play safe by using their workers to do

such acts. These observations clearly reflect the caste and class perception of

judges in deciding a case, whereas these observations were not uniquely the

societal understanding of judges, but these were the common perception, even

among the working class and lower caste population during this period.

the court held that the people who kept fire for the house are unaware that 44

people were inside and they had no intension to kill them. Are they so innocent

to not hear scream or lock a hut which is empty without any human being inside?

Based on certain frivolous interpretation of the evidences, the judges have

decided that the workers and communist leaders conspired to trap Gopala Krishna

Naidu in the case. The Supreme court also upheld this decision to set free the

landlords. The judges observation clearly accepted the caste position and

economic status of the landlords, and made this as basis to clear them of any

criminal intension. The land and cars owned by the landlords not only made them

superior, but also excluded them from involving in the cheap and direct act of

killing labourers. The judgement implies that only desperate hungry labourer (

lower caste) are capable of doing such stupid things and landlords being

economically wealthy ( upper caste) will not even enter the lower caste

dwellings and they are smart enough to play safe by using their workers to do

such acts. These observations clearly reflect the caste and class perception of

judges in deciding a case, whereas these observations were not uniquely the

societal understanding of judges, but these were the common perception, even

among the working class and lower caste population during this period.

Babri

Masjid – Ayodhya Case

Masjid – Ayodhya Case

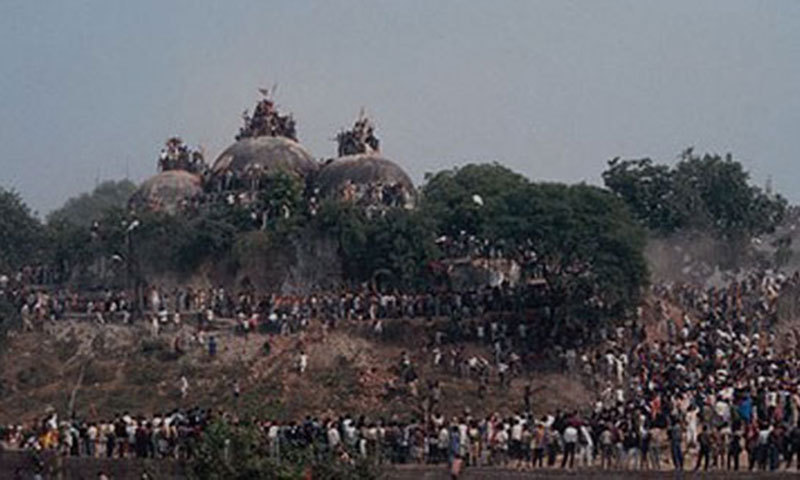

The Ramjanmabhoomi – Babri

Masjid controversy is still one of the major communal conflict in India, where a

site in Ayodhya was claimed by Muslims as a Mosque (Babri Masjid) and Hindus

claim it to be birthplace of Lord Ram. Even though, the issue is there from the

time before independence, it mainly got flared up and became an national issue

after 1986 district court judgement, which opened the gates for Hindus to

conduct prayers. This judgement triggered the communal issue to develop as one

the biggest communal conflict between Hindus and Muslims in independent India. This

became a great challenge to the secular fabric of India, which indeed has led to

nation-wide communal conflicts between Hindus and Muslims. A major political

reshaping in India

happened due to this conflict in post-independence period. The Bharatiya Janata

Party (BJP), which was at the fringes of electoral politics was able to make

use of this communal conflict to mobilise and also polarise Hindu votes in its

favour. So, more than religious issue, it has to be seen as a political issue,

which created space for the right-wing party in the parliamentary politics.

Masjid controversy is still one of the major communal conflict in India, where a

site in Ayodhya was claimed by Muslims as a Mosque (Babri Masjid) and Hindus

claim it to be birthplace of Lord Ram. Even though, the issue is there from the

time before independence, it mainly got flared up and became an national issue

after 1986 district court judgement, which opened the gates for Hindus to

conduct prayers. This judgement triggered the communal issue to develop as one

the biggest communal conflict between Hindus and Muslims in independent India. This

became a great challenge to the secular fabric of India, which indeed has led to

nation-wide communal conflicts between Hindus and Muslims. A major political

reshaping in India

happened due to this conflict in post-independence period. The Bharatiya Janata

Party (BJP), which was at the fringes of electoral politics was able to make

use of this communal conflict to mobilise and also polarise Hindu votes in its

favour. So, more than religious issue, it has to be seen as a political issue,

which created space for the right-wing party in the parliamentary politics.

Rather

than looking in detail, the Ayodhya controversy, we will look into the 1986

judgement by Justice K M Pandey, who gave judgement opening the gates for

worshipping by Hindus. On December 22nd, 1949, the Hindu right wing miscreants

secretly planted the Ram idol inside Babri Masjid, to garner further support

from the radical Hindus to claim the Masjid site for Ram Temple.

Both Hindu and Muslim sides filed civil suits for the ownership of the disputed

plot. Till 22nd December 1949, Muslims were offering Namaz in Babri Masjid

site, and the government locked the gates after that as the matter was

sub-judice (Puniyani, 2010). Even though

the gates were locked, the idol of Ram, which was installed illegally, was not

removed and restricted access to conduct pooja was given Hindus. For the next

35 years, Hindus were having access to the disputed site and Muslims were not

allowed. At this period, the demand of the Hindu right wing forces was to open

the locks of the gate for unlimited access for Hindus to worship at the

disputed site.

than looking in detail, the Ayodhya controversy, we will look into the 1986

judgement by Justice K M Pandey, who gave judgement opening the gates for

worshipping by Hindus. On December 22nd, 1949, the Hindu right wing miscreants

secretly planted the Ram idol inside Babri Masjid, to garner further support

from the radical Hindus to claim the Masjid site for Ram Temple.

Both Hindu and Muslim sides filed civil suits for the ownership of the disputed

plot. Till 22nd December 1949, Muslims were offering Namaz in Babri Masjid

site, and the government locked the gates after that as the matter was

sub-judice (Puniyani, 2010). Even though

the gates were locked, the idol of Ram, which was installed illegally, was not

removed and restricted access to conduct pooja was given Hindus. For the next

35 years, Hindus were having access to the disputed site and Muslims were not

allowed. At this period, the demand of the Hindu right wing forces was to open

the locks of the gate for unlimited access for Hindus to worship at the

disputed site.

The

1986 judgment, which opened the gates of communal fighting in India, has

finally conceded to the demands of Hindu right wing forces, which not only

changed the political landscape, but also taken numerous Hindu and Muslim

innocent lives due to communal conflict. The district judge K M Pandey, in his

judgement,

1986 judgment, which opened the gates of communal fighting in India, has

finally conceded to the demands of Hindu right wing forces, which not only

changed the political landscape, but also taken numerous Hindu and Muslim

innocent lives due to communal conflict. The district judge K M Pandey, in his

judgement,

“…it is

not necessary to keep the locks at the gates for the purpose of maintaining law

and order or the safety of the idols. This appears to be an unnecessary

irritant to the applicant and other members of the community. There does not

appear to be any necessity to create an artificial barrier between the idol and

the devotees. It appears that the opposite parties have remained a prisoner of

indecision for the last 35 years. Somebody in his wisdom thought fit to put

locks at the gates at any point of time and nobody since then has seen whether

there is any necessity to retain locks or not”(Puniyani, 2010 ; 43-44).

not necessary to keep the locks at the gates for the purpose of maintaining law

and order or the safety of the idols. This appears to be an unnecessary

irritant to the applicant and other members of the community. There does not

appear to be any necessity to create an artificial barrier between the idol and

the devotees. It appears that the opposite parties have remained a prisoner of

indecision for the last 35 years. Somebody in his wisdom thought fit to put

locks at the gates at any point of time and nobody since then has seen whether

there is any necessity to retain locks or not”(Puniyani, 2010 ; 43-44).

Further he

observed:

observed:

“after

having heard the parties it is clear that the members of the other community,

namely the Muslims, are not going to be affected by any stretch of imagination

if the locks of the gates were opened and the idols inside the premises are

allowed to be seen and worshipped by the pilgrims and devotees. It is

undisputed that the premises are presently in the court’s possession and that

for the last 35 years Hindus have had an unrestricted right or worship as a

result of the court’s order of 1950 and 1951. If the Hindus are offering

prayers and worshipping the idols, though in a restricted way for the last 35

years, then the heavens are not going to fall if the locks of the gates are

removed. The district magistrate has stated before me today that the members of

the Muslim community are not allowed to offer any prayers at the disputed site.

They are not allowed to go there. … If this is the state of affairs then there

is no occasion for any law and order problem arising as a result of the removal

of the locks. It is absolutely an affair inside the premises. There is no

justification for retaining locks after the positive statements of the district

magistrate and the SSP Faizabad that the law and order situation can be very

well kept under control by other means as well and for that end it is not

necessary to keep the locks on these gates”(Puniyani, 2010 ; 44).

having heard the parties it is clear that the members of the other community,

namely the Muslims, are not going to be affected by any stretch of imagination

if the locks of the gates were opened and the idols inside the premises are

allowed to be seen and worshipped by the pilgrims and devotees. It is

undisputed that the premises are presently in the court’s possession and that

for the last 35 years Hindus have had an unrestricted right or worship as a

result of the court’s order of 1950 and 1951. If the Hindus are offering

prayers and worshipping the idols, though in a restricted way for the last 35

years, then the heavens are not going to fall if the locks of the gates are

removed. The district magistrate has stated before me today that the members of

the Muslim community are not allowed to offer any prayers at the disputed site.

They are not allowed to go there. … If this is the state of affairs then there

is no occasion for any law and order problem arising as a result of the removal

of the locks. It is absolutely an affair inside the premises. There is no

justification for retaining locks after the positive statements of the district

magistrate and the SSP Faizabad that the law and order situation can be very

well kept under control by other means as well and for that end it is not

necessary to keep the locks on these gates”(Puniyani, 2010 ; 44).

This

opening of the locks for unrestricted access to Ram idol inside the Babri

Masjid, has not only strengthened the right wing communal forces , but also

shifted their demand towards having the ownership right for the disputed site

for building Ram temple and destroying the Babri Masjid structure, which is

there for more than 400 years. The district judge K M Pandey’s decision was

criticised by many ( even the 2010 Allahabad High Court judgement criticised

it), for his haste in opening the locks, which had a disastrous impact on the

communal situation and the minorities in the country. But, later when K M

Pandey wrote his memoir “Voice of Conscience“, published in

1996, he gave a reason for his decision on that day as

opening of the locks for unrestricted access to Ram idol inside the Babri

Masjid, has not only strengthened the right wing communal forces , but also

shifted their demand towards having the ownership right for the disputed site

for building Ram temple and destroying the Babri Masjid structure, which is

there for more than 400 years. The district judge K M Pandey’s decision was

criticised by many ( even the 2010 Allahabad High Court judgement criticised

it), for his haste in opening the locks, which had a disastrous impact on the

communal situation and the minorities in the country. But, later when K M

Pandey wrote his memoir “Voice of Conscience“, published in

1996, he gave a reason for his decision on that day as

” On the

date of the order when orders for opening locks was passed, a Black Monkey was

sitting for the whole day on the roof of the Court Room, in which hearing was

going on, holding the flag-post. Thousands of people of Faizabad and Ayodhya

who were present to hear the final orders of the Court had offered him

ground-nuts, various fruit. Strangely the said Monkey did not touch any of the

offerings and left the place when the final order was passed at 4.40 pm. The

District Magistrate and SSP escorted me to my bungalow. The said Monkey was

present in the verandah of my bungalow. I was surprised to see him. I just

saluted him treating him to be some Divine Power“(Pandey, 1996; 215).

date of the order when orders for opening locks was passed, a Black Monkey was

sitting for the whole day on the roof of the Court Room, in which hearing was

going on, holding the flag-post. Thousands of people of Faizabad and Ayodhya

who were present to hear the final orders of the Court had offered him

ground-nuts, various fruit. Strangely the said Monkey did not touch any of the

offerings and left the place when the final order was passed at 4.40 pm. The

District Magistrate and SSP escorted me to my bungalow. The said Monkey was

present in the verandah of my bungalow. I was surprised to see him. I just

saluted him treating him to be some Divine Power“(Pandey, 1996; 215).

The

judge decision to open the locks was not only in haste, but also firmly rooted

in his Hindu religious belief, which was politically constructed to be in

opposition to Muslims due to the Ayodhya- Babri Masjid conflict. The Judge in

this case failed to uphold objective and scientific way of analysing the

situation and being persuaded by his own belief system to come out with such a

judgement, which impacted the peaceful communal landscape of India.

Initially, by installing the idol inside the Mosque in 1949, the Muslims were

denied the right to worship and finally by this decision, the Babri Masjid was

made as de facto temple. Similar to Kizhvenmani case, where the judges were influenced by narrow understanding of class and caste, set

free the criminal Mr.Gopala Krishna Naidu, who burned and killed 44 Dalits for

demanding higher wages, here the judge being influenced by his narrow religious

understanding and superstition had deepened the communal divide within Indian

society by favouring religious Hindu section of the population, ignoring

deliberately, the fair and objective justice.

judge decision to open the locks was not only in haste, but also firmly rooted

in his Hindu religious belief, which was politically constructed to be in

opposition to Muslims due to the Ayodhya- Babri Masjid conflict. The Judge in

this case failed to uphold objective and scientific way of analysing the

situation and being persuaded by his own belief system to come out with such a

judgement, which impacted the peaceful communal landscape of India.

Initially, by installing the idol inside the Mosque in 1949, the Muslims were

denied the right to worship and finally by this decision, the Babri Masjid was

made as de facto temple. Similar to Kizhvenmani case, where the judges were influenced by narrow understanding of class and caste, set

free the criminal Mr.Gopala Krishna Naidu, who burned and killed 44 Dalits for

demanding higher wages, here the judge being influenced by his narrow religious

understanding and superstition had deepened the communal divide within Indian

society by favouring religious Hindu section of the population, ignoring

deliberately, the fair and objective justice.

Bhanwari Devi case

Bhanwari Devi was a Kumhar ( Dalit) women, around

40 years old, who was brutally gang raped by upper caste Gujjar men in her

village Bhateri, 55 km from Jaipur, Rajasthan in 1992. She was trained as

Sathin ( Grassroot Worker) to work in Women Development Programme of Rajasthan

government. Being a grassroot worker, she campaigned on many issues, including

a attempted rape case with the support of people from village. But when she

took up the issue of child marriage, which was prevalent in her society, she

was slowly alienated from the people. She carried forward the Rajasthan state

governments programme to end the child marriage. The Gujjar caste, which was

dominant in her village, was not happy with her campaign. The main contention

started when she tried to convince Ram Charan Gujjar, to stop marrying his one

year old girl child. Even though the marriage of that one year old girl was

stopped by the police initially, it was held the next day. After this incident,

the Gujjars started targeting Bhanwari Devi, accusing her of informing police and

interrupting their cultural practices. This targeting has forced her husband,

who was a rickshaw puller in Jaipur, to come back and stay with her to give her

protection. In this hostile environment, on 22nd September 1992, at 6 PM in

evening, Bhanwari Devi and her husband were attacked by five Gujjar men. They

also brutally gang raped her. The husband and wife, after much difficulty,

filed a case against the criminals. But, the police, medical doctors and the

village community were not cooperating at any stage, which led to delay of more

than 52 hours in conducting medical examination (Mathur,

1992).

40 years old, who was brutally gang raped by upper caste Gujjar men in her

village Bhateri, 55 km from Jaipur, Rajasthan in 1992. She was trained as

Sathin ( Grassroot Worker) to work in Women Development Programme of Rajasthan

government. Being a grassroot worker, she campaigned on many issues, including

a attempted rape case with the support of people from village. But when she

took up the issue of child marriage, which was prevalent in her society, she

was slowly alienated from the people. She carried forward the Rajasthan state

governments programme to end the child marriage. The Gujjar caste, which was

dominant in her village, was not happy with her campaign. The main contention

started when she tried to convince Ram Charan Gujjar, to stop marrying his one

year old girl child. Even though the marriage of that one year old girl was

stopped by the police initially, it was held the next day. After this incident,

the Gujjars started targeting Bhanwari Devi, accusing her of informing police and

interrupting their cultural practices. This targeting has forced her husband,

who was a rickshaw puller in Jaipur, to come back and stay with her to give her

protection. In this hostile environment, on 22nd September 1992, at 6 PM in

evening, Bhanwari Devi and her husband were attacked by five Gujjar men. They

also brutally gang raped her. The husband and wife, after much difficulty,

filed a case against the criminals. But, the police, medical doctors and the

village community were not cooperating at any stage, which led to delay of more

than 52 hours in conducting medical examination (Mathur,

1992).

The rapist tried to give her compensation for

not going ahead with the legal case against them. But, she bravely filed case

against them and fought in the court of law. The district sessions court

judgement in November 1995 shocked the conscience of all who fought for

Bhanwari Devi to get justice. The Judge said that an upper caste man could not

have raped a dalit women. The other main observations of the court are

not going ahead with the legal case against them. But, she bravely filed case

against them and fought in the court of law. The district sessions court

judgement in November 1995 shocked the conscience of all who fought for

Bhanwari Devi to get justice. The Judge said that an upper caste man could not

have raped a dalit women. The other main observations of the court are

“ a man could not possibly have participated in a gang rape in the

presence of his nephew; Bhanwari Devi could be lying that she was gang raped as

her medical examination happened a full 52 hours after the said event; and that

her husband couldn’t possibly have watched passively as his wife was being gang

raped — after all, had he not taken marriage vows which bound him to protect

her?”(Vij, 2007)

presence of his nephew; Bhanwari Devi could be lying that she was gang raped as

her medical examination happened a full 52 hours after the said event; and that

her husband couldn’t possibly have watched passively as his wife was being gang

raped — after all, had he not taken marriage vows which bound him to protect

her?”(Vij, 2007)

The case went for appeal, but the evidences were

fabricated and still they are waiting for the justice. The heights of casteism

and patriarchy was displayed, when after the district sessions court judgement,

the state BJP MLA organised a rally in support of the five rapist (Virani, 2001). But this

case and its judgement led to large public outcry and a many more public

interest litigation against the sexual harassment of women in workplace.

Finally, the Supreme Court issued Vishaka guidelines to be followed by all public and private

organisations and institutions to stop sexual harassment of women at workplace.

This case judgement shows the patriarchal attitude, which is prevalent in our

society, also influenced the judgment where a women complaining against

dominant men was not an acceptable behaviour. The casteism was also displayed

where the judge asks how a upper caste men can rape a lower caste women? Such

common perceptions that were prevailing in our society

gets reflected in the judgment, ignoring the objective and scientific way of

bringing justice for the oppressed sections of our society.

fabricated and still they are waiting for the justice. The heights of casteism

and patriarchy was displayed, when after the district sessions court judgement,

the state BJP MLA organised a rally in support of the five rapist (Virani, 2001). But this

case and its judgement led to large public outcry and a many more public

interest litigation against the sexual harassment of women in workplace.

Finally, the Supreme Court issued Vishaka guidelines to be followed by all public and private

organisations and institutions to stop sexual harassment of women at workplace.

This case judgement shows the patriarchal attitude, which is prevalent in our

society, also influenced the judgment where a women complaining against

dominant men was not an acceptable behaviour. The casteism was also displayed

where the judge asks how a upper caste men can rape a lower caste women? Such

common perceptions that were prevailing in our society

gets reflected in the judgment, ignoring the objective and scientific way of

bringing justice for the oppressed sections of our society.

Observations

As we

saw in the beginning, even though the domain of law and its institutional

structure seems to be independent and objective in bringing justice to

everyone, it is still being impacted by the societal attitude and values in its

outcome, as it is part of the larger societal structure. The three case

judgment Kizhvenmani, Ayodhya ( 1986) and Bhanwari Devi that we analysed here

shows how the existing societal values of casteism, patriarchy and communalism

are dominant within the legal institutions, which apparently gets displayed in

the final judgments. Thus trying to comprehend the legal institution and its

outcome, without locating it in a larger political society and its values, will

be a futile exercise, resulting in mere technical analysis of law and its

provisions, devoid of any political space to use law as an effective tool for

fighting against all forms of exploitation.

saw in the beginning, even though the domain of law and its institutional

structure seems to be independent and objective in bringing justice to

everyone, it is still being impacted by the societal attitude and values in its

outcome, as it is part of the larger societal structure. The three case

judgment Kizhvenmani, Ayodhya ( 1986) and Bhanwari Devi that we analysed here

shows how the existing societal values of casteism, patriarchy and communalism

are dominant within the legal institutions, which apparently gets displayed in

the final judgments. Thus trying to comprehend the legal institution and its

outcome, without locating it in a larger political society and its values, will

be a futile exercise, resulting in mere technical analysis of law and its

provisions, devoid of any political space to use law as an effective tool for

fighting against all forms of exploitation.

References

Balu, M.

(2009). Nindru Keduttha Neethi : Venmani Vazhakku – Pathivugalum

Theerpugalum (Tamil). Chennai: Alaigal Veliyeetagam.

(2009). Nindru Keduttha Neethi : Venmani Vazhakku – Pathivugalum

Theerpugalum (Tamil). Chennai: Alaigal Veliyeetagam.

Cerar, M.

(2009). The Relationship Between Law and Politics. Annual Survey of

International & Comparative Law , 15 (1), 19-41.

(2009). The Relationship Between Law and Politics. Annual Survey of

International & Comparative Law , 15 (1), 19-41.

EPW. (1973).

Gentlemen Killers of Kilvenmani. Economic and Political Weekly , 926 –

928.

Gentlemen Killers of Kilvenmani. Economic and Political Weekly , 926 –

928.

Gough, K.

(1976). Indian Peasant Uprisings. Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars ,

8 (3), 2 – 18.

(1976). Indian Peasant Uprisings. Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars ,

8 (3), 2 – 18.

Kanagasabai,

N. (2014). The Din of Silence : Reconstructing the Keezhvenmani Dalit Massacre

of 1968. SubVersions , 2 (1), 105-130.

N. (2014). The Din of Silence : Reconstructing the Keezhvenmani Dalit Massacre

of 1968. SubVersions , 2 (1), 105-130.

Mather, L.

(2008). Law and Society. In K. E. WHITTINGTON, R. D. KELEMEN, & G. A.

CALDEIRA, The Oxford Handbook of Law and Politics (pp. 681 – 697). Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

(2008). Law and Society. In K. E. WHITTINGTON, R. D. KELEMEN, & G. A.

CALDEIRA, The Oxford Handbook of Law and Politics (pp. 681 – 697). Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Mathur, K.

(1992). Bhateri Rape Case: Backlash and Protest. Economic and Political

Weekly , 2221 – 2224.

(1992). Bhateri Rape Case: Backlash and Protest. Economic and Political

Weekly , 2221 – 2224.

Pandey, K. M.

(1996). Voice of Conscience. Lucknow:

Din Dayal Upadhyay Parkashan.

(1996). Voice of Conscience. Lucknow:

Din Dayal Upadhyay Parkashan.

Puniyani, R.

(2010). Ayodhya: Masjid-Mandir Dispute : Towards Peaceful Solution.

Mumbai: Center for Study of Society and Secularism.

(2010). Ayodhya: Masjid-Mandir Dispute : Towards Peaceful Solution.

Mumbai: Center for Study of Society and Secularism.

Stone, A.

(1985). The Place of Law in the Marxian Structure – Superstructure Archetype. Law

& Society Review , 19 (01), 39-68.

(1985). The Place of Law in the Marxian Structure – Superstructure Archetype. Law

& Society Review , 19 (01), 39-68.

Vij, S. (2007,

October 13). A Mighty Heart. Retrieved August 22nd, 2016, from Tehelka:

http://archive.tehelka.com/story_main34.asp?filename=hub131007A_MIGHTY.asp

October 13). A Mighty Heart. Retrieved August 22nd, 2016, from Tehelka:

http://archive.tehelka.com/story_main34.asp?filename=hub131007A_MIGHTY.asp

Virani, P.

(2001, March 4). Long wait for justice. Retrieved August 21st, 2016,

from The Hindu: http://www.thehindu.com/2001/03/04/stories/13040611.htm

(2001, March 4). Long wait for justice. Retrieved August 21st, 2016,

from The Hindu: http://www.thehindu.com/2001/03/04/stories/13040611.htm

Viswanathan,

S. (2006, January 14). Keezhavenmani Revisited. Retrieved August 21,

2016, from Frontline:

http://www.frontline.in/navigation/?type=static&page=flonnet&rdurl=fl2301/stories/20060127001608400.htm

S. (2006, January 14). Keezhavenmani Revisited. Retrieved August 21,

2016, from Frontline:

http://www.frontline.in/navigation/?type=static&page=flonnet&rdurl=fl2301/stories/20060127001608400.htm

The author is an associate professor at Department of Political Science and International Relations, College of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Asmara, Eritrea. His email id is svnarayanan15@gmail.com