Savera

|

|

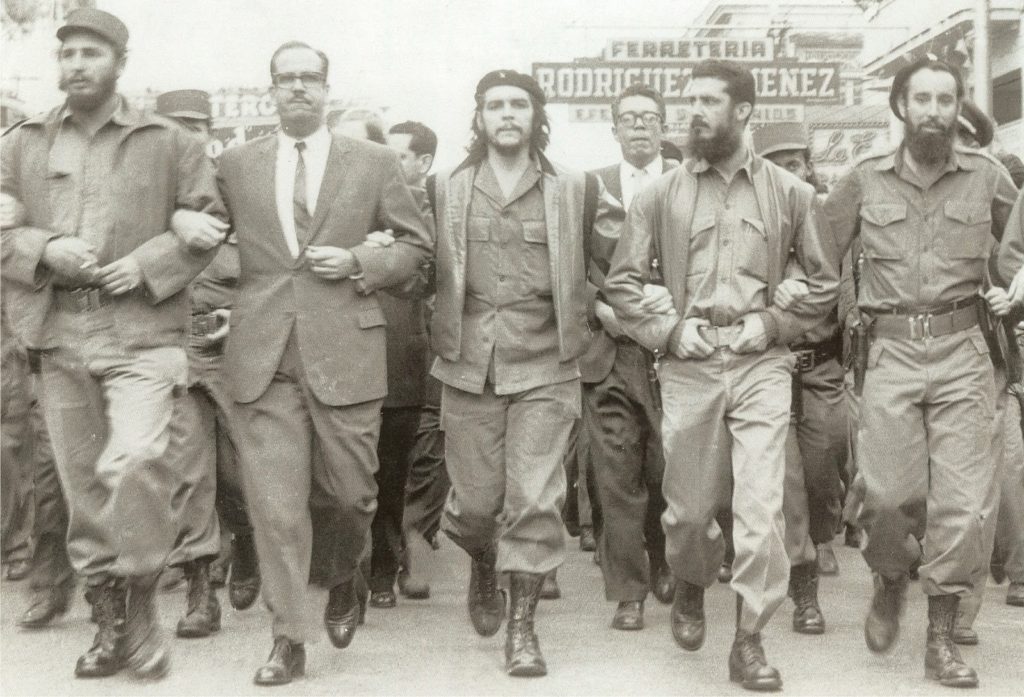

Raúl (left) and Fidel Castro in the Sierra

Maestra,1959 |

It was in

the twentieth century that humanity took the first steps to free itself of

class rule, ending thousands of years of oppression and exploitation. The

October Revolution in Russia in 1917 was followed by the Chinese revolution in

1949. Both were big countries, mighty empires. The defeat of their rulers by

their own people caused the whole world to sit up. The world capitalist order

was panic stricken. It launched a vicious war of attrition against the

socialist camp and tried to crush communism elsewhere in the world.

the twentieth century that humanity took the first steps to free itself of

class rule, ending thousands of years of oppression and exploitation. The

October Revolution in Russia in 1917 was followed by the Chinese revolution in

1949. Both were big countries, mighty empires. The defeat of their rulers by

their own people caused the whole world to sit up. The world capitalist order

was panic stricken. It launched a vicious war of attrition against the

socialist camp and tried to crush communism elsewhere in the world.

But only

a decade after the Chinese revolution, in 1959, a tiny island in the Caribbean

Sea saw another people’s upsurge, which swept aside a hated military dictatorship.

The island was Cuba, located just 90 miles from the United States. Such was the

anger and panic among the ruling capitalist classes that they swore to destroy

this new revolution before it could take roots. They feared that it would serve

as a beacon to the whole of Latin America, which was treated as its backyard by

US imperialism.

a decade after the Chinese revolution, in 1959, a tiny island in the Caribbean

Sea saw another people’s upsurge, which swept aside a hated military dictatorship.

The island was Cuba, located just 90 miles from the United States. Such was the

anger and panic among the ruling capitalist classes that they swore to destroy

this new revolution before it could take roots. They feared that it would serve

as a beacon to the whole of Latin America, which was treated as its backyard by

US imperialism.

Cuba had

been a colony for over four hundred years, initially of the Spanish, then of

the British and finally, since the beginning of the twentieth century, of the

United States. This meant that the vast majority of its people worked like

slaves in plantations and mines, filling the coffers of barons in Europe and

US. There were several attempts to get rid of colonial rulers, or their puppet

rulers in Cuba, but they were either failures or short lived.

been a colony for over four hundred years, initially of the Spanish, then of

the British and finally, since the beginning of the twentieth century, of the

United States. This meant that the vast majority of its people worked like

slaves in plantations and mines, filling the coffers of barons in Europe and

US. There were several attempts to get rid of colonial rulers, or their puppet

rulers in Cuba, but they were either failures or short lived.

The final

stage can be said to begin in 1952 when General Batista seized power as

installed himself as the president in Havana. His ruthless rule, his open

kowtowing with US corporations, and his greed in looting the country’s wealth

led to increasing public anger against him. In 1953, a group of about 180 men

attempted to storm the army garrison at Moncada, but they were badly defeated.

The leader of this attack was a fiery young man called Fidel Castro. He and his

comrades were imprisoned. In his trial, Fidel gave a famous speech that laid

bare the injustice of Batista’s rule. He ended by saying, “Condemn me, it does

not matter. History will absolve me.”

stage can be said to begin in 1952 when General Batista seized power as

installed himself as the president in Havana. His ruthless rule, his open

kowtowing with US corporations, and his greed in looting the country’s wealth

led to increasing public anger against him. In 1953, a group of about 180 men

attempted to storm the army garrison at Moncada, but they were badly defeated.

The leader of this attack was a fiery young man called Fidel Castro. He and his

comrades were imprisoned. In his trial, Fidel gave a famous speech that laid

bare the injustice of Batista’s rule. He ended by saying, “Condemn me, it does

not matter. History will absolve me.”

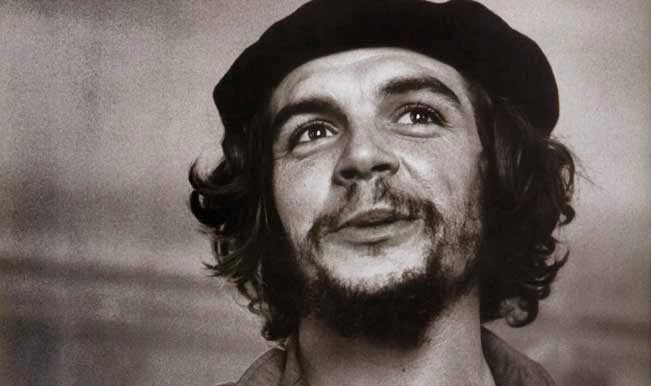

Fidel and

Fidel andhis comrades were released from prison in 1955 due to huge public pressure on

Batista. They went into exile in Mexico where another great Argentinian

revolutionary Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara joined them. Secretly, they trained in the

jungles for taking on the well-equipped army of Gen. Batista. They called

themselves the 26th July Movement, after the date of the failed

attack on the Moncada garrison. Thus began the final preparations for throwing

out the dictator in Havana and freeing the people from neo-colonial yoke.

Cuba,

meanwhile continued to bleed under the jackboots of the dictatorship and the

exploitation of US corporations. Over three quarters of all arable land was

owned by US corporations. By the late 1950’s, American capital controlled 90%

of Cuba’s mines (mainly nickel and cobalt), 80% of its public utilities, 50% of

its railways, 40% of its sugar production and 25% of its bank deposits. They

paid a pittance to the labourers, and extracted enormous profits from their

labour. At the end of the fifties, US corporations were earning about $77

million in profit from Cuba – that would be about $560 million in today’s

value! Although there were several political groups actively fighting against

the dictatorship, there was no uniting thread, and, most importantly, the vast

mass of peasants in far flung villages were largely untouched by these

movements.

meanwhile continued to bleed under the jackboots of the dictatorship and the

exploitation of US corporations. Over three quarters of all arable land was

owned by US corporations. By the late 1950’s, American capital controlled 90%

of Cuba’s mines (mainly nickel and cobalt), 80% of its public utilities, 50% of

its railways, 40% of its sugar production and 25% of its bank deposits. They

paid a pittance to the labourers, and extracted enormous profits from their

labour. At the end of the fifties, US corporations were earning about $77

million in profit from Cuba – that would be about $560 million in today’s

value! Although there were several political groups actively fighting against

the dictatorship, there was no uniting thread, and, most importantly, the vast

mass of peasants in far flung villages were largely untouched by these

movements.

So, this

was the condition when, on 25 November 1956, 82 men set sail from the Mexican

coast on an old yacht called ‘Granma’. Their destination was Cuba and their

objective was to initiate an uprising to throw out the dictatorship. This band

of men included Fidel Castro, Raul Castro, Che Guevara, Camillo Cienfuegos.

They landed on Cuban coast a week later, little knowing that a disaster awaited

them. Just three days after landing they were attacked by the army – only 15

men survived. They had only 7 rifles between them. Dispirited, tired and

hungry, they took to the SieraMaestra, a mountain range in the south of Cuba.

As Che said later, “we were able to continue on, owing solely to the enormous

confidence of Fidel Castro at those decisive moments, to his firmness as a

revolutionary leader and his unbreakable faith in the people”.

was the condition when, on 25 November 1956, 82 men set sail from the Mexican

coast on an old yacht called ‘Granma’. Their destination was Cuba and their

objective was to initiate an uprising to throw out the dictatorship. This band

of men included Fidel Castro, Raul Castro, Che Guevara, Camillo Cienfuegos.

They landed on Cuban coast a week later, little knowing that a disaster awaited

them. Just three days after landing they were attacked by the army – only 15

men survived. They had only 7 rifles between them. Dispirited, tired and

hungry, they took to the SieraMaestra, a mountain range in the south of Cuba.

As Che said later, “we were able to continue on, owing solely to the enormous

confidence of Fidel Castro at those decisive moments, to his firmness as a

revolutionary leader and his unbreakable faith in the people”.

In the

next two years – 761 days, to be precise – these men mobilized an army of about

9000 dedicated fighters, carried out a relentless guerilla war against an army

that boasted of 80,000 conscripts, armed with the latest weapons sent by Uncle

Sam across the sea, and ultimately liberated the whole country.

next two years – 761 days, to be precise – these men mobilized an army of about

9000 dedicated fighters, carried out a relentless guerilla war against an army

that boasted of 80,000 conscripts, armed with the latest weapons sent by Uncle

Sam across the sea, and ultimately liberated the whole country.

It was a

time of intense difficulties, as the guerrillas moved from village to village

in the mountains, hiding and attacking the army units that came after them in

ever increasing numbers. There were heroic battles in various places and all of

them had only one result – the rebels defeated the army despite being

outnumbered 10 to one. They seized the arms and vehicles of the troops and used

them in the next battle.

time of intense difficulties, as the guerrillas moved from village to village

in the mountains, hiding and attacking the army units that came after them in

ever increasing numbers. There were heroic battles in various places and all of

them had only one result – the rebels defeated the army despite being

outnumbered 10 to one. They seized the arms and vehicles of the troops and used

them in the next battle.

In 1958,

Batista received $1 million in military aid from the U.S. All of Batista’s

arms, planes, tanks, ships, and military supplies came from the U.S., and a

joint mission of the U.S. armed forces trained his army.

Batista received $1 million in military aid from the U.S. All of Batista’s

arms, planes, tanks, ships, and military supplies came from the U.S., and a

joint mission of the U.S. armed forces trained his army.

Western

media often portrays this war in romantic terms, as if these 15 young men

single-handedly brought down a government. There could be nothing further from

truth. The role of the original band of men, who, alongwith some men and women

who later joined them, cannot be underestimated. They were the core leadership,

they provided the ideological framework, the military tactics, and the

indomitable will to complete the task. But could it have been achieved just by them

alone? Let us see what Che has to say about this.

media often portrays this war in romantic terms, as if these 15 young men

single-handedly brought down a government. There could be nothing further from

truth. The role of the original band of men, who, alongwith some men and women

who later joined them, cannot be underestimated. They were the core leadership,

they provided the ideological framework, the military tactics, and the

indomitable will to complete the task. But could it have been achieved just by them

alone? Let us see what Che has to say about this.

“The

peasant was the invisible collaborator who did everything that the rebel

combatant could not. He supplied us with information, kept watch on the enemy,

discovered its weak points, rapidly brought urgent messages, spied on the very

ranks of Batista’s army”, said Che, just a few weeks after the revolution

succeeded. The key to the success was the immense support that the Cuban

peasantry extended to the rebel army. And this came about not by a miracle but

because the rebels decided to keep the agrarian question in the forefront. They

seized land from the agents of the corporations and landlords, and distributed

it amongst the peasants. They seized 10,000 heads of cattle from large dairies

and distributed them among peasants. They set up schools where children of

villagers started learning. They set up small workshops for making or repairing

farm implements – and weapons when the need arose.

peasant was the invisible collaborator who did everything that the rebel

combatant could not. He supplied us with information, kept watch on the enemy,

discovered its weak points, rapidly brought urgent messages, spied on the very

ranks of Batista’s army”, said Che, just a few weeks after the revolution

succeeded. The key to the success was the immense support that the Cuban

peasantry extended to the rebel army. And this came about not by a miracle but

because the rebels decided to keep the agrarian question in the forefront. They

seized land from the agents of the corporations and landlords, and distributed

it amongst the peasants. They seized 10,000 heads of cattle from large dairies

and distributed them among peasants. They set up schools where children of

villagers started learning. They set up small workshops for making or repairing

farm implements – and weapons when the need arose.

As Che

later described it, a massive shift took place in the peasantry – “For the

first time, the guajiros [peasants] of the Sierra, in this miserably poor

region, had their well-being addressed. For the first time, peasant children

drank milk and ate beef. And for the first time too, they received the benefits

of education, because the revolution brought schools along with it. In this way

the peasants in their entirety came over to our side”.

later described it, a massive shift took place in the peasantry – “For the

first time, the guajiros [peasants] of the Sierra, in this miserably poor

region, had their well-being addressed. For the first time, peasant children

drank milk and ate beef. And for the first time too, they received the benefits

of education, because the revolution brought schools along with it. In this way

the peasants in their entirety came over to our side”.

Another

factor that helped the partisan war was the urban resistance. Although in many

places it was led by other political groups but as time passed it coalesced.

The assassination of Frank Pai’s, a leader in Santiago-de-Cuba, by Batista’s

thugs was followed by a huge 60,000 strong demonstration and strike. In 1958, a

general strike was called which did not succeed. But it led to a consolidation

of the urban resistance with the guerrilla war.

factor that helped the partisan war was the urban resistance. Although in many

places it was led by other political groups but as time passed it coalesced.

The assassination of Frank Pai’s, a leader in Santiago-de-Cuba, by Batista’s

thugs was followed by a huge 60,000 strong demonstration and strike. In 1958, a

general strike was called which did not succeed. But it led to a consolidation

of the urban resistance with the guerrilla war.

In other

words, the revolution succeeded because it became the revolution of all

oppressed people of Cuba. And when this massive strength was unleashed, the US

backed army was blown away.

words, the revolution succeeded because it became the revolution of all

oppressed people of Cuba. And when this massive strength was unleashed, the US

backed army was blown away.

It would

not be correct to think that the Cuban revolution ended with the victorious

rebels entering Havana on 1 January 1959. The Revolution still continues. In

the past fifty seven years, Cuba’s people have built a more just and free

society, defended themselves against economic and military attacks by

imperialism, helped struggling people all over the world and thus held out hope

for everyone. This building of a new society is the revolution.

not be correct to think that the Cuban revolution ended with the victorious

rebels entering Havana on 1 January 1959. The Revolution still continues. In

the past fifty seven years, Cuba’s people have built a more just and free

society, defended themselves against economic and military attacks by

imperialism, helped struggling people all over the world and thus held out hope

for everyone. This building of a new society is the revolution.

BOX 1

Excerpts

from Speech given by Fidel Castro Ruz, first secretary of the Central

Committee of the Communist Party of Cuba and president of the Councils of State

and Ministers, at the main ceremony for the 40th anniversary of the triumph of

the Revolution, in Santiago de Cuba, on January 1, 1999.

from Speech given by Fidel Castro Ruz, first secretary of the Central

Committee of the Communist Party of Cuba and president of the Councils of State

and Ministers, at the main ceremony for the 40th anniversary of the triumph of

the Revolution, in Santiago de Cuba, on January 1, 1999.

People of

Santiago: Compatriots in all of Cuba:

Santiago: Compatriots in all of Cuba:

I am

trying to recall that night of January 1, 1959; I am reliving and perceiving

impressions and details as if everything were occurring at this very moment. It

seems unreal that destiny has given us the rare privilege of once more speaking

to the people of Santiago de Cuba from this very same place, 40 years later.

trying to recall that night of January 1, 1959; I am reliving and perceiving

impressions and details as if everything were occurring at this very moment. It

seems unreal that destiny has given us the rare privilege of once more speaking

to the people of Santiago de Cuba from this very same place, 40 years later.

Before

dawn on that day, with the arrival of the news that the dictator and the main

figures of his opprobrious regime had fled in the face of the irrepressible

advance of our forces, for a few seconds I felt a strange sensation of

emptiness. How was that incredible victory possible in just over 24 months,

starting from that moment on December 18, 1956, when – after the extremely

severe setback which virtually annihilated our detachment – we managed to

gather together seven rifles to resume the battle against a combination of

military forces which totaled 800,000 armed men, thousands of trained officers,

high morale, attractive privileges, a totally unquestioned myth of

invincibility, infallible advising and guaranteed supplies from the United

States? Just ideas which a valiant people claimed as their own worked a

military and political victory. Subsequent vain and ridiculous attempts to

salvage what remained of that exploiting and oppressive system were swept away

by the Rebel Army, the workers and the rest of the people in 24 hours.

dawn on that day, with the arrival of the news that the dictator and the main

figures of his opprobrious regime had fled in the face of the irrepressible

advance of our forces, for a few seconds I felt a strange sensation of

emptiness. How was that incredible victory possible in just over 24 months,

starting from that moment on December 18, 1956, when – after the extremely

severe setback which virtually annihilated our detachment – we managed to

gather together seven rifles to resume the battle against a combination of

military forces which totaled 800,000 armed men, thousands of trained officers,

high morale, attractive privileges, a totally unquestioned myth of

invincibility, infallible advising and guaranteed supplies from the United

States? Just ideas which a valiant people claimed as their own worked a

military and political victory. Subsequent vain and ridiculous attempts to

salvage what remained of that exploiting and oppressive system were swept away

by the Rebel Army, the workers and the rest of the people in 24 hours.

Our

fleeting sadness at the moment of victory was nostalgia for the experiences we

had lived through, the vivid memory of the comrades who fell throughout the

struggle, a full awareness that those exceptionally difficult and adverse years

obliged us to be better than we were, and to transform them into the most fruitful

and creative ones of our lives. We had to abandon our mountains, our rural

life, our habits of absolute and obligatory austerity, our tense life of

constant vigilance in the face of an enemy that could appear by land or air at

any moment of the 761 days of the war; a healthy, hard, pure life and one of

great sacrifices and shared dangers, in which men become brothers and their

best virtues flourish, together with the infinite capacity for commitment,

selflessness and altruism that all humans carry within them.

fleeting sadness at the moment of victory was nostalgia for the experiences we

had lived through, the vivid memory of the comrades who fell throughout the

struggle, a full awareness that those exceptionally difficult and adverse years

obliged us to be better than we were, and to transform them into the most fruitful

and creative ones of our lives. We had to abandon our mountains, our rural

life, our habits of absolute and obligatory austerity, our tense life of

constant vigilance in the face of an enemy that could appear by land or air at

any moment of the 761 days of the war; a healthy, hard, pure life and one of

great sacrifices and shared dangers, in which men become brothers and their

best virtues flourish, together with the infinite capacity for commitment,

selflessness and altruism that all humans carry within them.

The

enormous difference in equipment and strength between the enemy and us forced

us to do the impossible. Suffice it to say that we won the war with rifles and

anti-tank mines, in every important action always fighting against the enemy’s

artillery, armored vehicles and, in particular, airplanes, which were always

immediately present in any military action.

enormous difference in equipment and strength between the enemy and us forced

us to do the impossible. Suffice it to say that we won the war with rifles and

anti-tank mines, in every important action always fighting against the enemy’s

artillery, armored vehicles and, in particular, airplanes, which were always

immediately present in any military action.

We seized

rifles and other semi-automatic and automatic light infantry weapons from the

enemy in combat, and the explosives with which, in rustic workshops, we

manufactured the shells we used against armored vehicles and their accompanying

infantry always came from the rain of bombs which they launched against us,

some of which failed to explode. The infallible tactic of attacking the enemy when

it was on the move was a key factor. The art of provoking those forces into

moving out of their well-fortified and generally invulnerable positions became

one of our commands’ greatest skills.

rifles and other semi-automatic and automatic light infantry weapons from the

enemy in combat, and the explosives with which, in rustic workshops, we

manufactured the shells we used against armored vehicles and their accompanying

infantry always came from the rain of bombs which they launched against us,

some of which failed to explode. The infallible tactic of attacking the enemy when

it was on the move was a key factor. The art of provoking those forces into

moving out of their well-fortified and generally invulnerable positions became

one of our commands’ greatest skills.

Box 2

Excerpts from speech by Che Guevara at a ceremony

in Havana Jan. 27, 1959, sponsored by the cultural organization NuestroTiempo

(Our Epoch). Guevara had been asked to speak on the topic “The Social Aims

of the Rebel Army”.

Transformation

into army of peasants

into army of peasants

What is

of interest to me, and what is important, I believe, are the social ideas of

the survivors of Alegri’a de Pi’o. This was the first and only disaster that

the armed rebels suffered over the course of the insurrection. About fifteen

men, physically and even morally destroyed, were reunited, and we were able to

continue on owing solely to the enormous confidence of Fidel Castro at those

decisive moments, to his firmness as a revolutionary leader and his unbreakable

faith in the people.

of interest to me, and what is important, I believe, are the social ideas of

the survivors of Alegri’a de Pi’o. This was the first and only disaster that

the armed rebels suffered over the course of the insurrection. About fifteen

men, physically and even morally destroyed, were reunited, and we were able to

continue on owing solely to the enormous confidence of Fidel Castro at those

decisive moments, to his firmness as a revolutionary leader and his unbreakable

faith in the people.

We were a

group of city people who were thrown into the Sierra Maestra, but were not part

of it. We walked from hut to hut and touched nothing that did not belong to us.

We did not even eat anything we were unable to pay for, and often went hungry

as a result of this principle. The peasants looked with tolerance on our group,

but did not join it. This went on for some time. We spent several months

wandering through the highest peaks of the Sierra Maestra, making sporadic

attacks and returning to higher ground. We traveled from one peak to another, where

there was little water and living conditions were extremely difficult.

group of city people who were thrown into the Sierra Maestra, but were not part

of it. We walked from hut to hut and touched nothing that did not belong to us.

We did not even eat anything we were unable to pay for, and often went hungry

as a result of this principle. The peasants looked with tolerance on our group,

but did not join it. This went on for some time. We spent several months

wandering through the highest peaks of the Sierra Maestra, making sporadic

attacks and returning to higher ground. We traveled from one peak to another, where

there was little water and living conditions were extremely difficult.

Little by

little the peasants’ view toward us began to change, spurred by the actions of

Batista’s repressive forces, who devoted themselves to murdering people and

destroying homes and who were utterly hostile toward those who even

occasionally had the slightest contact with our Rebel Army. The shift in the

peasants’ attitude translated into the incorporation of palm-leaf hats into our

ranks, as our army of city folk was becoming transformed into an army of

peasants.

little the peasants’ view toward us began to change, spurred by the actions of

Batista’s repressive forces, who devoted themselves to murdering people and

destroying homes and who were utterly hostile toward those who even

occasionally had the slightest contact with our Rebel Army. The shift in the

peasants’ attitude translated into the incorporation of palm-leaf hats into our

ranks, as our army of city folk was becoming transformed into an army of

peasants.

As

peasants yearning for freedom and social justice joined the armed struggle, the

great magic words agrarian reform began to mobilize the oppressed masses of

Cuba in their struggle for possession of the land. Thus emerged our first

pronouncement on a major social issue. Agrarian reform would later become the

banner and main slogan of our movement-although we passed through a stage of

considerable uneasiness owing to natural concerns related to the policy and

conduct of our great neighbor to the north.

peasants yearning for freedom and social justice joined the armed struggle, the

great magic words agrarian reform began to mobilize the oppressed masses of

Cuba in their struggle for possession of the land. Thus emerged our first

pronouncement on a major social issue. Agrarian reform would later become the

banner and main slogan of our movement-although we passed through a stage of

considerable uneasiness owing to natural concerns related to the policy and

conduct of our great neighbor to the north.

General

strike in Santiago de Cuba

strike in Santiago de Cuba

Around

that time in Santiago de Cuba, a very tragic event occurred: the murder of our

companero Frank Pai’s, an event that marked a turning point in the entire

structure of the revolutionary movement. Responding to the emotional impact

caused by Frank Pai’s’s death, the people of Santiago de Cuba spontaneously

went out into the streets, producing the first attempt at a political general

strike. Although leaderless, the strike completely paralyzed Oriente and had

similar repercussions in Camaguey and Las Villas.

that time in Santiago de Cuba, a very tragic event occurred: the murder of our

companero Frank Pai’s, an event that marked a turning point in the entire

structure of the revolutionary movement. Responding to the emotional impact

caused by Frank Pai’s’s death, the people of Santiago de Cuba spontaneously

went out into the streets, producing the first attempt at a political general

strike. Although leaderless, the strike completely paralyzed Oriente and had

similar repercussions in Camaguey and Las Villas.

The

dictatorship crushed this movement, which arose without preparation or

revolutionary control. The massive character of the response made us realize

the necessity of incorporating into the struggle for Cuba’s liberation the

great social force constituted by the workers. Underground efforts in the

workplaces immediately began, to prepare a general strike that would help the

Rebel Army to conquer power.

dictatorship crushed this movement, which arose without preparation or

revolutionary control. The massive character of the response made us realize

the necessity of incorporating into the struggle for Cuba’s liberation the

great social force constituted by the workers. Underground efforts in the

workplaces immediately began, to prepare a general strike that would help the

Rebel Army to conquer power.

That was

the beginning of an insurrectional campaign by underground organizations. Those

who gave encouragement to these movements, however, did not really understand

the mass struggle or its tactics. The work was conducted in completely mistaken

ways: a revolutionary spirit was not created, unity of the combatants was not

achieved, and attempts were made to lead the strike from above, without

effective roots among the ranks of the strikers.

the beginning of an insurrectional campaign by underground organizations. Those

who gave encouragement to these movements, however, did not really understand

the mass struggle or its tactics. The work was conducted in completely mistaken

ways: a revolutionary spirit was not created, unity of the combatants was not

achieved, and attempts were made to lead the strike from above, without

effective roots among the ranks of the strikers.

The

victories of the Rebel Army and the difficult and painstaking clandestine

efforts stirred the country, creating a state of ferment so great that it

provoked the declaration of a general strike on April 9 of last year. That

effort failed precisely due to errors of organization, primarily lack of

contact between the mass of workers and the leadership, as well as the

leadership’s mistaken approach.

victories of the Rebel Army and the difficult and painstaking clandestine

efforts stirred the country, creating a state of ferment so great that it

provoked the declaration of a general strike on April 9 of last year. That

effort failed precisely due to errors of organization, primarily lack of

contact between the mass of workers and the leadership, as well as the

leadership’s mistaken approach.

But the

experience was put to good use, and an ideological struggle arose within the

July 26 Movement that led to a radical shift in the organization’s view of the

country’s reality and its sectors of action. The July 26 Movement emerged

strengthened from the failed strike. That experience taught its leaders a

precious truth, which was-and is-that the revolution did not belong to any one

group, but had to be the work of the entire Cuban people. All the energies of

our movement’s members, both in the cities and in the mountains, were channeled

toward this end.

experience was put to good use, and an ideological struggle arose within the

July 26 Movement that led to a radical shift in the organization’s view of the

country’s reality and its sectors of action. The July 26 Movement emerged

strengthened from the failed strike. That experience taught its leaders a

precious truth, which was-and is-that the revolution did not belong to any one

group, but had to be the work of the entire Cuban people. All the energies of

our movement’s members, both in the cities and in the mountains, were channeled

toward this end.

At

precisely this time, the Rebel Army began its first steps to provide a theory

and doctrine to the revolution, giving tangible proof that the insurrectional

movement had grown and therefore attained political maturity. We had passed

from the experimental stage to the constructive one, from trial and error to

definitive acts.

precisely this time, the Rebel Army began its first steps to provide a theory

and doctrine to the revolution, giving tangible proof that the insurrectional

movement had grown and therefore attained political maturity. We had passed

from the experimental stage to the constructive one, from trial and error to

definitive acts.

Immediately

we began the work of creating small-scale industries in the Sierra Maestra. A

change occurred that our forebears had seen many years ago: we passed from a

nomadic life to a settled one; we created centers of production in accordance

with our most pressing needs. Thus we founded our shoe factory, our weapons

factory, our workshop to rebuild the bombs that the tyranny dropped on us,

giving them back to Batista’s soldiers in the form of land mines.

we began the work of creating small-scale industries in the Sierra Maestra. A

change occurred that our forebears had seen many years ago: we passed from a

nomadic life to a settled one; we created centers of production in accordance

with our most pressing needs. Thus we founded our shoe factory, our weapons

factory, our workshop to rebuild the bombs that the tyranny dropped on us,

giving them back to Batista’s soldiers in the form of land mines.

First

act of agrarian reform

act of agrarian reform

The men

and women of the Rebel Army never forgot their fundamental mission in the

Sierra Maestra or in other areas, which was to improve the conditions of the

peasants and to incorporate them into the struggle for the land. Schools were

set up, in which improvised teachers went to the most inaccessible parts of

this region of Oriente.

and women of the Rebel Army never forgot their fundamental mission in the

Sierra Maestra or in other areas, which was to improve the conditions of the

peasants and to incorporate them into the struggle for the land. Schools were

set up, in which improvised teachers went to the most inaccessible parts of

this region of Oriente.

There in

the Sierra we made the first effort at dividing up the land, with an agrarian

law drafted principally by Dr. Humberto Sori’ Mari’n(8) and by Fidel Castro,

and in which I had the honor of collaborating. The land was given to the

peasants in a revolutionary manner. The large farms belonging to servants of

the dictatorship were seized and divided up, and all state lands began to be

put in the hands of the region’s peasants. The moment had arrived in which we

identified ourselves fully as a peasant movement closely linked to the land,

and with agrarian reform as our banner.

the Sierra we made the first effort at dividing up the land, with an agrarian

law drafted principally by Dr. Humberto Sori’ Mari’n(8) and by Fidel Castro,

and in which I had the honor of collaborating. The land was given to the

peasants in a revolutionary manner. The large farms belonging to servants of

the dictatorship were seized and divided up, and all state lands began to be

put in the hands of the region’s peasants. The moment had arrived in which we

identified ourselves fully as a peasant movement closely linked to the land,

and with agrarian reform as our banner.

This was

a war in which we always relied on the people, that priceless ally of such

extraordinary valor. Our columns were able to continually evade the enemy and

situate themselves in the best positions, thanks not only to tactical

advantages and the morale of our militiamen, but to a very large extent because

of the great assistance of the peasants.

a war in which we always relied on the people, that priceless ally of such

extraordinary valor. Our columns were able to continually evade the enemy and

situate themselves in the best positions, thanks not only to tactical

advantages and the morale of our militiamen, but to a very large extent because

of the great assistance of the peasants.

The

peasant was the invisible collaborator who did everything that the rebel

combatant could not. He supplied us with information, kept watch on the enemy,

discovered its weak points, rapidly brought urgent messages, spied on the very

ranks of Batista’s army. This was not the result of any miracle; it was because

we had energetically begun to implement our policy of responding to the

peasants’ demands. In the face of the bitter attack and circle of hunger that

enveloped the Sierra Maestra, ten thousand head of cattle were taken from the

landlords of the surrounding region and brought up to the mountains. This move

was not intended to supply the Rebel Army alone; the cattle were also

distributed among the peasants. For the first time, the guajiros [peasants] of

the Sierra, in this miserably poor region, had their well-being addressed. For

the first time, peasant children drank milk and ate beef. And for the first

time too, they received the benefits of education, because the revolution

brought schools along with it. In this way the peasants in their entirety came

over to our side.

peasant was the invisible collaborator who did everything that the rebel

combatant could not. He supplied us with information, kept watch on the enemy,

discovered its weak points, rapidly brought urgent messages, spied on the very

ranks of Batista’s army. This was not the result of any miracle; it was because

we had energetically begun to implement our policy of responding to the

peasants’ demands. In the face of the bitter attack and circle of hunger that

enveloped the Sierra Maestra, ten thousand head of cattle were taken from the

landlords of the surrounding region and brought up to the mountains. This move

was not intended to supply the Rebel Army alone; the cattle were also

distributed among the peasants. For the first time, the guajiros [peasants] of

the Sierra, in this miserably poor region, had their well-being addressed. For

the first time, peasant children drank milk and ate beef. And for the first

time too, they received the benefits of education, because the revolution

brought schools along with it. In this way the peasants in their entirety came

over to our side.

Box 3

Cuba – A chronology of key events

1492 –

The navigator Christopher Columbus claims Cuba for Spain.

The navigator Christopher Columbus claims Cuba for Spain.

1511 – Spanish conquest begins under the

leadership of Diego de Velazquez, who establishes Baracoa and other

settlements.

leadership of Diego de Velazquez, who establishes Baracoa and other

settlements.

1526 –

Importing of slaves from Africa begins.

Importing of slaves from Africa begins.

1762 –

Havana captured by a British force led by Admiral George Pocock and Lord

Albemarle.

Havana captured by a British force led by Admiral George Pocock and Lord

Albemarle.

1763 –

Havana returned to Spain by the Treaty of Paris.

Havana returned to Spain by the Treaty of Paris.

Wars of independence

1868-78 –

Ten Years War of independence ends in a truce with Spain promising reforms and

greater autonomy – promises that were mostly never met.

Ten Years War of independence ends in a truce with Spain promising reforms and

greater autonomy – promises that were mostly never met.

1886 –

Slavery abolished.

Slavery abolished.

1895-98 –

Jose Marti leads a second war of independence; US declares war on Spain.

Jose Marti leads a second war of independence; US declares war on Spain.

1898 – US

defeats Spain, which gives up all claims to Cuba and cedes it to the US.

defeats Spain, which gives up all claims to Cuba and cedes it to the US.

US tutelage

1902 –

Cuba becomes independent with Tomas Estrada Palma as its president; however,

the Platt Amendment keeps the island under US protection and gives the US the

right to intervene in Cuban affairs.

Cuba becomes independent with Tomas Estrada Palma as its president; however,

the Platt Amendment keeps the island under US protection and gives the US the

right to intervene in Cuban affairs.

1906-09 –

Estrada resigns and the US occupies Cuba following a rebellion led by Jose

Miguel Gomez.

Estrada resigns and the US occupies Cuba following a rebellion led by Jose

Miguel Gomez.

1909 –

Jose Miguel Gomez becomes president following elections supervised by the US,

but is soon tarred by corruption.

Jose Miguel Gomez becomes president following elections supervised by the US,

but is soon tarred by corruption.

1912 – US

forces return to Cuba to help put down black protests against discrimination.

forces return to Cuba to help put down black protests against discrimination.

1924 –

Gerado Machado institutes vigorous measures, forwarding mining, agriculture and

public works, but subsequently establishing a brutal dictatorship.

Gerado Machado institutes vigorous measures, forwarding mining, agriculture and

public works, but subsequently establishing a brutal dictatorship.

1925 –

Socialist Party founded, forming the basis of the Communist Party.

Socialist Party founded, forming the basis of the Communist Party.

1933 –

Machado overthrown in a coup led by Sergeant Fulgencio Batista.

Machado overthrown in a coup led by Sergeant Fulgencio Batista.

1934 –

The US abandons its right to intervene in Cuba’s internal affairs, revises

Cuba’s sugar quota and changes tariffs to favour Cuba.

The US abandons its right to intervene in Cuba’s internal affairs, revises

Cuba’s sugar quota and changes tariffs to favour Cuba.

1944 –

Batista retires and is succeeded by the civilian Ramon Gray San Martin.

Batista retires and is succeeded by the civilian Ramon Gray San Martin.

1952 –

Batista seizes power again and presides over an oppressive and corrupt regime.

Batista seizes power again and presides over an oppressive and corrupt regime.

1953 –

Moncada Attack – Fidel Castro leads an unsuccessful revolt against the Batista

regime.

Moncada Attack – Fidel Castro leads an unsuccessful revolt against the Batista

regime.

1956 –

Castro lands in eastern Cuba from Mexico and takes to the Sierra Maestra

mountains where, aided by Ernesto “Che” Guevara, he wages a guerrilla

war.

Castro lands in eastern Cuba from Mexico and takes to the Sierra Maestra

mountains where, aided by Ernesto “Che” Guevara, he wages a guerrilla

war.

1958 –

The US withdraws military aid to Batista.

The US withdraws military aid to Batista.

Triumph of the revolution

1959 –

Castro leads a 9,000-strong guerrilla army into Havana, forcing Batista to

flee. Castro becomes prime minister, his brother, Raul, becomes his deputy and

Guevara becomes third in command.

Castro leads a 9,000-strong guerrilla army into Havana, forcing Batista to

flee. Castro becomes prime minister, his brother, Raul, becomes his deputy and

Guevara becomes third in command.

1960 –

All US businesses in Cuba are nationalised without compensation; US breaks off

diplomatic relations with Havana.

All US businesses in Cuba are nationalised without compensation; US breaks off

diplomatic relations with Havana.

1961 – US

sponsors an abortive invasion by Cuban exiles at the Bay of Pigs; Castro

proclaims Cuba a communist state and begins to ally it with the USSR.

sponsors an abortive invasion by Cuban exiles at the Bay of Pigs; Castro

proclaims Cuba a communist state and begins to ally it with the USSR.

1962 –

Cuban missile crisis ignites when, fearing a US invasion, Castro agrees to

allow the USSR to deploy nuclear missiles on the island. The crisis was

subsequently resolved when the USSR agreed to remove the missiles in return for

the withdrawal of US nuclear missiles from Turkey.

Cuban missile crisis ignites when, fearing a US invasion, Castro agrees to

allow the USSR to deploy nuclear missiles on the island. The crisis was

subsequently resolved when the USSR agreed to remove the missiles in return for

the withdrawal of US nuclear missiles from Turkey.

1965 –

Cuba’s sole political party renamed the Cuban Communist Party.

Cuba’s sole political party renamed the Cuban Communist Party.