Suchetana Chattopadhyay

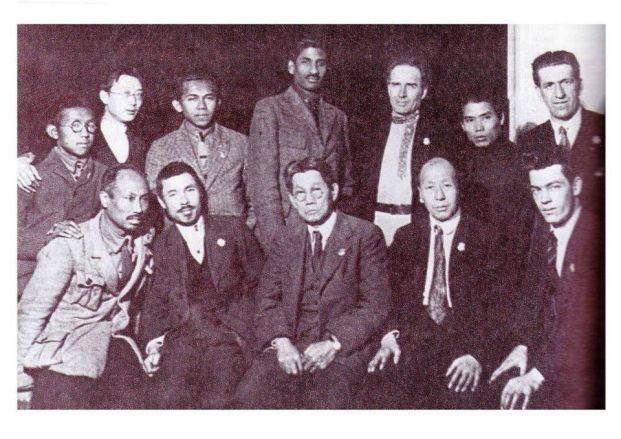

(Prisoners in the Meerut Conspiracy Case. Shaukat Usmani (ex-Muhajir communist) fourth from left in the back row)

Before the emergence of a communist movement within India, there was the tendency. It emerged from the passage of the muhajirs, Muslims religious exiles from colonial India during the First World War and post-war turmoil. Following the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, they reached civil war torn formerly Czarist Central Asia through Afghanistan. From their ranks emerged an émigré communist party. Though the impact of their initiatives was limited by their external locations and repression by the colonial state, they represented the earliest left collective effort related to the Indian subcontinent. The article will explore the experiences and shifting contexts in the course of their journey through certain contiguous terrains of revolutionary dissent which made them abandon pan-Islamist anti-imperialism and turn to communism.

Lahore to Kabul

In the era of Balkan War and the beginning of First World War, pan-Islamism, as a political ideology upholding the unity of Sunni Islam and the authority of its Caliph, the Ottoman Emperor, gained popularity as one of the chief vehicles of anti-colonialism in India. The sovereign authority of the British Crown could be viewed from this perspective as a temporal constraint. A student group emerged in the Government College at Lahore, the capital city of Punjab, led by Khushi Mohammad. Planning to set the premises ablaze, their immature militancy amounted to smashing a glass-door, and acquiring minor hand injury in the process.

In January 1915, Khushi joined a group of friends who had sworn to undertake ‘hijrat’. The colonial intelligence deployed the gamut of orientalist knowledge to explain their motivation, observing that the general term applied to these ‘runaway students’ was muhajirin, the plural of muhajir, meaning one who performed hijrat (that is, flight or migration). An Arabic word describing those who abandoned their country due to religious persecution, hijrat referred to the historic instance of hijrat or flight from Mecca to Medina by the prophet Mohammad in the early 7th Century. Among the 15 students who escaped from Lahore and headed towards Afghanistan, most were from middle-class families in decline or impoverished agrarian and artisanal families of Punjab. Khushi Mohammad’s father and grandfather were village oilmen, a manual profession. The exposure to a paradoxical modernity of colonial rule, which promised prosperity through education while denying the same in practice and draining the material resources of their surroundings on behalf of colonial capital, as well as concrete experience of repression and racism, propelled these students towards pan-Islam. Not seeking a medieval Caliphate, they wished to live in Muslim societies undergoing modernisation. Afghanistan, far from being a bold utopia of Islamic resurgence, was to disappoint them.

Kabul to Tashkent

They reached a rebel settlement at Asmas, a border village politely labeled by British officials as the ‘colony of Hindustani Fanatics’. A bastion of the mujahidin or holy warriors waging a jihad against the British Empire since the 19th Century, they received preliminary military training there. The poverty of the place was overwhelming. Convinced that resistance to imperialism was better built elsewhere, the students proceeded to Kabul by a route used since antiquity by travellers and merchants, with overlapping cultural influences of Greek settlers, Buddhism and Islam. In Kabul, the fugitives became close followers of Obeidullah Sindhi, a respected pan Islamist preacher exiled from India. In October 1915, the Indian-Turkish-German Mission also arrived and failed to convince Amir Habibullah to join the anti-British alliance. Squeezed between Czarist Central Asia and British India, the Afghan government was keen to placate Britain and imposed draconian restrictions on the muhajirs. To paraphrase one of the students, from guests of the Afghan government they were reduced to the status of donkeys. The top leaders of the muhajirs, intent on the worldly pursuit of setting up mercantile enterprises across the Muslim world, found their ambitions thwarted. In 1915, under Obeidullah’s guidance, the students formed an ‘Army of God’; the wing of a Provisional Government of India. Obeidullah’s military knowledge prompted the British colonial intelligence to note that the army of holy war was upside down; it was devoid of soldiers and possessed ‘few subordinate officers’ with 2 generals, including Obeidullah, 30 lieutenant generals, 16 major-generals, 24 colonels, 10 lieutenant-colonels, 5 majors, 2 captains and 1 lieutenant. Sindhi and the muhajirs, however, envisioned a secular constitutional government, presiding over a multi-religious population rather than a military-theocratic dictatorship for India once political freedom was attained. With this aim, they studied the British parliamentary model with interest alongside the Koran.

The post-war situation improved slightly when an anti-British Amir ascended the throne. By this time, the political and social aspirations of the exiles stood shattered. They could not take the risk of returning to India; so they turned further west towards Russian Central Asia and Turkey.

At of the end of 1919, Khushi Mohammad travelled to Tashkent, the headquarters of Bolshevik Turkestan.

Route to Tashkent and Moscow

(Tashkent, 1917)

While the muhajirs in Kabul were searching for support in Turkestan, a huge exodus began from India and their numbers in Afghanistan swelled unexpectedly. The hijrat of 1920 became a movement. Almost 40,000 refugees crossed into Afghanistan. The muhajirs keen to join the anti-British war led by Mustafa Kemal in Turkey were allowed to leave. According to M. N. Roy around ‘200 Khilafat pilgrims’ arrived in rags at Russian Turkestan. Some muhajir students, much like the ones who had escaped to Kabul from Lahore in 1915, recalled being warmly welcomed by an assorted crowd of Turkmen, Uzbeks, Tajiks and Russians at Tirmiz. A band played the ‘Internationale’ and the ‘Red Flag’ in their honour. After the cautious and restricted hospitality in Afghanistan, they were bewildered. The Civil-War, having virtually ended in the west was raging in Central Asia with British support. Tirmiz, cut off from the region and governed by an elected revolutionary committee comprising workers, peasants, students, soldiers, was like a Bolshevik island. The majority of the muhajirin wished to move on to Turkey; they fell into the hands of the rebels, were treated as infidels, and faced incarceration, semi starvation and possible execution. Rescued by the Red Army, 36 immediately joined Bolshevik military detachments comprising Russians and red Turkmen to fight the counter-revolutionary forces. They were impressed by the example of young Bokharans who had formed a communist party in Tashkent and were active in the new revolutionary government. Confiscation and redistribution of land among the peasants, a revolutionary programme, enjoyed popular support and the general mood of the place influenced them. Meanwhile, M. N. Roy, the nationalist turned-communist from India who had reached Russia via Mexico was entrusted by the Bolshevik authorities to look after them. Roy was not at all optimistic that pan-Islamists would take easily to Bolshevism. He nursed a cautious hope that some will join the civil-war on the Bolshevik side against the British-backed counter-revolutionaries and respond to the offer of military training to liberate India. He requisitioned clothes, housing and food for them in Tashkent. An American Wobbly, the Commandant of the military and political school to train the muhajirs, sarcastically remarked upon observing his charges: ‘We are going to train not an army of revolution, but an army of God.’ Roy had already mobilised Indian Muslim deserters from the British colonial army, enlisting them into Red Army’s international detachments.

Deployed against the British forces in Central Asia’s borders, some were raised to officer rank, a status denied to subalterns in the colonial army. Roy later recalled: ‘The news of their experience could not be kept away from their comrades still in colonial army, and it had a disintegrating effect. The number of deserters increased daily.’ Roy made no effort to form a communist party from the ranks of the enthusiastic deserters, mostly peasants in uniform. His previous nationalist training of organising educated and alienated middle-class Hindu upper caste youth in Bengal, probably influenced him to seek communist recruits from the muhajir students. He met and persuaded Khushi Mohammad to become a communist through dialogue and conversations and turned to other young muhajir students from India, about 50 in number, enrolled in the Indian Military School in Tashkent. The India House, a one storey building became the residence of the muhajirs, including students. Though the majority wanted to join the Kemalists in Turkey, a large section wanted to learn revolutionary techniques from the Bolsheviks and apply them in India. They were not keen to move on. A small section was interested in the ongoing social experiment accompanying the Bolshevik revolution.

The inner life of India House at Tashkent came to showcase the differences over the Bolshevik Revolution among the muhajirs. Roy recalled that the Bolsheviks provided the Indian muhajirs with all the basic comforts at a time when they themselves were undergoing extreme hardship.

No attempt was made to forcibly turn the muhajirs into communists. Only elementary political training was offered. A house committee was formed so that the emigrants could manage their own affairs. Despite their suspicion of communism, some managed to overcome their initial prejudice against an atheist creed. This led to a split among the muhajirs. In the end, the section that had turned left wished to form a communist party despite Roy’s cautious insistence that there was no hurry. Their pressure led to the formation of an émigré communist party in Tashkent in late October 1920. Mohammad Shafiq, described by Roy as an ‘intelligent and fairly educated young man’ became the secretary. They held regular lectures at the lodging to attract more members, avoided attacking religion, did not utter the word ‘communism’ but promoted a vision of mass revolution from below to liberate India. This was different from the positions advocated by nationalist militants or pan-Islamist preachers. According to Roy, one of the students who had taken part in the hijrat of 1920, Shaukat Usmani, ‘intelligent and the most fanatical’ became a communist; his lectures began to have an influence on the others.

Usmani, unaware of Roy’s cynical assessments, later wrote that Roy was like a ‘father-figure’ to them and there were differences between the pan-Islamists and Roy’s group in India House over communism and religion. For a while, Usmani steered clear of both groups but ultimately joined the communists. Encouraged to read Marx and having poor idea of industrial capitalism (since he came from a region with little modern industry), he found words such as the ‘bourgeoisie’ and the ‘proletariat’ to constitute a funny yet intriguing interpretive vocabulary. When asked to read about trade unionism, he impatiently declared, he was not interested in trade and industry, which made Roy and his ‘American wife’ and comrade Evelyn burst into laughter. However, he rapidly took to the socialist and internationalist vocabulary of the Comintern and read extensively on the conditions of workers and peasants in colonial and semi-colonial countries.

The novelty, social weight and political force of certain ideas over others made some of the muhajir students turn to communism in an atmosphere of chaos, civil-war and revolution. The social content of their anti-imperialism as members of a colonised intelligentsia was transformed under the combined impact of circumstances and new thinking. The Bolshevik support to post-war movements against colonialism and semi-colonialism in Asia and friendly relations with Turkey and Afghanistan since all were confronting British invasion, made many muhajir students turn left. The process involved rejecting the visions of state and society offered by Indian pan-Islamist and nationalist leaders. Instead of adopting the proffered model of a constitutional government which conserved proprietor authority and kept the rule of private property intact, some were turning to a new model of governance based on self-rule of the poor. Coming from the milieu of a derooted intelligentsia and impoverished agrarian classes, they were familiar with penury and destitution. The second route evoked an empathy for governance from below and persuaded them to join the Bolsheviks. The Second Congress of the Communist International placed communist parties at the centre of future revolutions across the world. Roy played a key role. He persuaded Lenin and the Comintern to accept his ‘Supplementary Thesis on the Colonial Question’; Roy argued the struggle for national liberation from imperialism could not be left in the hands of nationalists, prone to make compromises and reinforce class inequality; communist parties had to be formed with the aim of organising workers and peasants so that national liberation became an anti-imperialist and revolutionary class-war in the colonial and semi-colonial countries. This was followed by the Baku Congress of the Peoples of the East in September 1920, emphasising the role of mass uprisings to dismantle the formal and informal empires of capital.

It was this environment of internationalist revolutionary surge from European Russia to Central Asia, with a novel perspective that combined a vision of class-struggle with anti-imperialist political and social liberation, which contributed to the making of a party-in-exile. The party remained minute in terms of size though its membership increased. After the conclusion of the Anglo-Russian Trade Agreement in March 1921, effectively ending the civil-war, the muhajirs interested in further training, around 36 to 40 in number joined the University of the Toilers of the East at Moscow from mid-1921. Roy, with a degree of sadness, arranged for the rest of the muhajirs, around 100 or so, to be given money so that they could either settle in Central Asia or head for Turkey or return to Afghanistan or India. The ex-Muhajir communists planned to join the ongoing anti-colonial mass upsurge in India and establish contact in labour circles. Usmani, who thrived in the internationalist milieu by making friends with Chinese and Indonesian students, forced Roy to let him leave for India in September 1921. 19 months later, Usmani was arrested as Roy had feared and ultimately convicted in the Kanpur Bolshevik Conspiracy Case of 1924, alongside Muzaffar Ahmad, S. A. Dange, already active in Calcutta and Bombay and Nalini Gupta, Roy’s emissary. When he left Moscow, Usmani was unaware that the ex-muhajirs were already being arrested from June 1921 onwards by the colonial state. Secret trials and rigorous imprisonment awaited them at Peshawar, the frontier city. Their long and eventful journey was coming to an end.

Conclusion: flight from Lahore, return to Peshawar

‘Times like the present bring to the surface secret and long forgotten currents.’ This poetic line from the Sedition Committee (Rowlatt) Report of 1918 on Muslim Indian revolutionaries ended with the observation: ‘For the purpose of accomplishing their objects they seek to co-operate with enemies of Britain…Always they preach sedition.’

This imperial understanding of Muslim rebels as peripatetic, transterritorial, dangerous subversives in the employ of hostile powers was extended to the Muhajirs-turned-communists when they crossed over into India from Afghanistan. Despite the gaps in the years between 1915 and 1920, their passages led them through rebel territories and zones of anti-colonial inter-mixing during war-time and at the war’s end. Through a trail of old cities, they experienced different forms of governments and societies undergoing chaotic transition through regime-change and revolution. They came to learn of intersecting anti-imperialist routes with divergent social content and political programmes that led in different directions.

Among the original runaways of 1915 and post-war travelers of 1920, the voyage of the muhajirs evoked a varied response. Some became active in the Comintern, a few resided in the Soviet Union, others returned to India or settled in Turkey. Among the 7 convicted in the Peshawar Bolshevik Conspiracy Case of 1922-23, some remained with the communist movement, partially or wholly during the 1920s or even later. By inserting spies among the muhajirin between 1915 and 1920, the colonial intelligence laboriously tracked their movements. One of the secret agents, Abdur Qadir, while offering a full account of their travel to Tashkent and Moscow, perhaps unconsciously hinted at the social dimension of their political transformation which visited the muhajirs who turned left: ‘The term by which communists, including ourselves refer to each other is ‘Tawarish’, which means Comrade.’ For those who remained on the left, an altered perspective came to influence the way they related at a deeper level, politically and socially, to the world. Abdul Majid convicted at Peshawar, returned to Lahore, his home-city, upon release from prison. Addressing a meeting organised by a leftwing Punjabi youth group, Majid spoke of his first-hand experience as a muhajir in Central Asia, the conditions in Afghanistan, the encounter with Turkmen counterrevolutionaries, and the futility of pan-Islamist politics. He had sought but failed to attain emancipation within an identarian structure, forever withholding an elusive promise of Islamic brotherhood and unity. From a muhajir, he had become a Bolshevik.

Suchetana Chattopadhyay teaches history at Jadavpur University.

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 10.0px 0.0px; text-align: justify; font: 12.0px ‘Trebuchet MS’; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}

p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 10.0px 0.0px; text-align: justify; font: 12.0px ‘Trebuchet MS’; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000; min-height: 14.0px}

span.s1 {font-kerning: none}