p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 10.0px 0.0px; text-align: justify; font: 12.0px ‘Trebuchet MS’; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000}

p.p2 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 10.0px 0.0px; text-align: justify; font: 12.0px ‘Trebuchet MS’; -webkit-text-stroke: #000000; min-height: 14.0px}

span.s1 {font-kerning: none}

Suchetana Chattopadhyay

The leading states affiliated with the military alliance known as North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) held commemorations earlier this month to remember those who died in the First World War. The official framing of the mourning observations was accompanied by impish smiles of the leaders as they looked forward to further increasing the bloated military budgets. This brings us to certain elementary questions which persist. They simply refuse to go away. Why was the war started? Who paid for the war with their lives, labour and resources? What was the immediate impact of the war? How is the war being remembered now?

1.

Scholars do not subscribe to the official interpretations and conventional accounts of a century long ‘blame-game’ and finger-pointing by the rival imperial states who started the war. They have persuasively demonstrated that the deadly competition between the big powers reached a toxic climax in the form of an immensely destructive war in 1914. Imperialism, the underlying cause of the war, had triggered tremendous brutality in the colonial territories of Asia, Africa and Latin America. It was now returning to unleash havoc within Europe. Though the war was chiefly confined to Europe and Asia-minor, it had a worldwide material impact by subjecting the colonies and semi-colonies to conditions of starvation and death by draining their resources. Prabhat Patnaik, following Marx and Lenin, argues centralisation of capital or the formation of ever larger blocs of capital culminated in the emergence of monopoly capital. Big banks, a handful in number came to control the most profitable branches of financial transactions, production and trade in the imperial states of the west and their colonies and semi-colonies. The ‘coalescence’ of banking and industrial capital, including manufacture of weapons of mass destruction, came to constitute a financial oligarchy and shaped the era of ‘monopoly capital’. ‘Monopoly capital’ of the times was based on imperial nation-states. The monopoly combines could therefore be identified as British, French, German, American etc. The financial oligarchies in the era of monopoly capital penetrated state structures and directed state policies. Big power rivalry underlined by inter-imperialist competition over territorial expansion and exploitation of colonial/semi-colonial resources erupted into war. Eric Hobsbawm has pointed out that all previous wars had been fought with specific aims. This war, shaped by violent rivalry among the capitalist powers who were more or less equal in strength, was aimed at elimination of power blocs created by the competing nation-states. It was fought with the unlimited expansion of capitalism in mind: this explains the ferocity of the conflict.

Image: Indian Soldiers during First World War

2.

The devastating impact of the First World War is known. According to certain estimates, 6000 soldiers died every day on an average in the course of the war. At the end of the war, though the calculations vary, out of 65 million soldiers mobilised, roughly 20 million were killed and 21 million wounded. 40 million people died including 10 million civillians. Let us look at the casualty figures of the principal belligerent powers. 800, 000 British men were killed. Among them, 500, 000 were under the age of thirty including some of the leading War Poets. 1.6 million French soldiers, 1.8 million German soldiers, 5.5 million Russian soldiers and more than 100,000 American soldiers perished. The end of the war brought a sinister gift: an influenza epidemic which killed 50 million people across the world. In Kolkata, in the course of October-November-December 1918, official health records showed nearly thirty thousand people had died. They were mostly children, women and the elderly belonging to poor families and suffering from malnutrition and lack of medical facilities. Who remembers them?

Image: Ganganendranath Tagore’s image of Colonial Capital

The belligerent powers drew on colonial resources and used European and other working-class civilians by transforming them into military labour and exploiting their labour-power in the war industries. The warring European states whipped up xenophobic hysteria among ordinary people in the name of nationalism and even forced reluctant subjects to go to war. Jaroslav Hasek’s ‘The Good Soldier Svejk’ and Erich Maria Remarque’s ‘All Quiet on the Western Front’, written after the war, exposed the corruptions and cynicism of the military authorities who regarded the lives of soldiers as expendable. Women, children and prisoners of war provided cheap or unfree labour in the factories producing commodities to support the war-effort. The salaries of workers remained frozen and accidents at work increased as super-profits piled up in the stock-markets of the capital cities of the principal belligerents. Those who emerged victorious, namely the Anglo-French Alliance, were supported by men and money taken from the colonies. France exploited the cheap labour of Vietnamese workers in the armament factories and used Moroccan soldiers as cannon-fodder. Britain mobilised more than a million soldiers from India as military labour to fight in Western Europe, Mesopotamia and elsewhere. Nearly 75000 Indian soldiers died. Chinese coolies, unarmed, were transported from their villages to Southern France to dig trenches in the face of German machine-gun fire. There were mutinies in British and French Armies, cases of mass desertion in the Czarist Russian Army which fuelled the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, a short-lived uprising in the German Army suppressed in the course of 1918-19 and revolt by colonial troops. If caught, the deserters and mutineers faced the firing squad. On 15 February 1915 Punjabi Muslim garrisons in Singapore turned their guns on the British officers. These soldiers were suppressed with utmost brutality. As for the flow of money, Sumit Sarkar has pointed out that the ‘drain of wealth’ led to massive plunder of India’s material resources. The defence expenditure was increased by 300%. Semi-compulsory ‘war loans’ were imposed on the colonial economy. There was a sharp rise in taxes and steep fall in the living standards for the majority of the population in India.

Image: Executions following Singapore mutiny

3.

Though the First World War formally ended in November 1918, the victors led by Britain immediately attacked Bolshevik Russia, Afghanistan and post-Ottoman Turkey, thereby informally prolonging bloody conflict and were ultimately defeated on all three fronts. As the borders of the empires of capital were reorganised, Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, Jordan, Palestine and Egypt became formal colonies of Britain and France. By this time, petroleum had been identified as the energy source of the future. Few remember what happened in colonial cities, seemingly untouched by war, such as Kolkata. On the day of Armistice, the colonial authorities held a huge parade in the maidan. The victory celebrations were accompanied by the influenza epidemic, the ‘war fever’. The war induced inflated prices of food and cloth had kept rising from 1914 to 1918. Scarcity had led to thousands of unrecorded deaths from hunger. Though the war officially ended, the prices did not climb down. This was because the colonial regime had scant regard for the concept of price control-the Bengal Chamber of Commerce was firmly against any intervention to check the prices. Starving conditions and resulting protests, suppressed during the war, found a direct outlet in post-war anti-colonial mass upsurge and waves of industrial strike actions directed against colonial capital.

4.

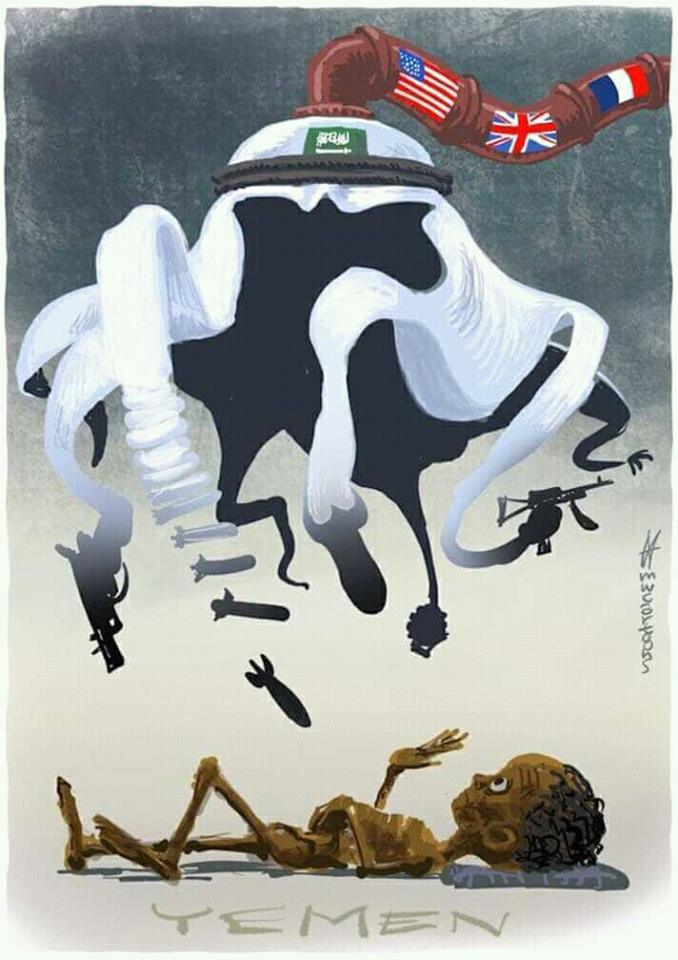

A hundred years later, national commemorations are being held by the major western powers. The principal belligerents, Britain, France and Germany are keen to project the First World War as national tragedies never to be repeated. On the date of Armistice, more military aid has been pledged by the European Union (EU) to sustain war in West Asia and NATO continues to trigger genocidal conflict. To paraphrase Vijay Prashad, wars are raging from the Atlas Mountains to the Hindukush. Millions of civilians have died in the regions lying in between from aerial bombardment and starvation, from weapons of mass destruction manufactured by Lockheed Martin and other big armament producing corporations located in the West, firmly entrenched within the military-industrial complex. At this moment, Yemen faces one of the worst famines in recorded history due to war unleashed by Saudi Arabia, with generous assistance from the US-UK-EU Alliance. As the most powerful states of the planet continue to pursue the goals of imperialism, who determines the ‘global’ scales of remembering the dead from Afghanistan to Iraq, from Syria to Libya? Who counts the dead? Who mourns the mass casualties of imperialism in our times?

A hundred years later, national commemorations are being held by the major western powers. The principal belligerents, Britain, France and Germany are keen to project the First World War as national tragedies never to be repeated. On the date of Armistice, more military aid has been pledged by the European Union (EU) to sustain war in West Asia and NATO continues to trigger genocidal conflict. To paraphrase Vijay Prashad, wars are raging from the Atlas Mountains to the Hindukush. Millions of civilians have died in the regions lying in between from aerial bombardment and starvation, from weapons of mass destruction manufactured by Lockheed Martin and other big armament producing corporations located in the West, firmly entrenched within the military-industrial complex. At this moment, Yemen faces one of the worst famines in recorded history due to war unleashed by Saudi Arabia, with generous assistance from the US-UK-EU Alliance. As the most powerful states of the planet continue to pursue the goals of imperialism, who determines the ‘global’ scales of remembering the dead from Afghanistan to Iraq, from Syria to Libya? Who counts the dead? Who mourns the mass casualties of imperialism in our times?

Suchetana Chattopadhyay teaches history at Jadavpur University.

References:

Aijaz Ahmad, Iraq, Afghanistan & The Imperialism of Our Time, Delhi 2004.

Amiya Kumar Bagchi, Perilous Passage: Mankind and the Global Ascendancy of Capital, Lanham 2005.

Upendra Narayan Chakraborty, Indian Nationalism and the First World War (1914-1918), Calcutta 1997.

Suchetana Chattopadhyay, ‘War-time in an Imperial City: The Apocalyptic Mood in Calcutta (1914-1918)’ in Roger D. Long and Ian Talbot (ed.), India and World War I: A Centennial Assessment, New York 2018.

Marc Ferro, The Great War 1914-1918, New York 2001.

Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Empire 1875-1914, New York 1989.

Eric Hobsbawnm, The Age of Extremes 1914-1991, New York 1996.

V. I. Lenin, Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism (April 1917).

Pankaj Mishra, ‘How colonial violence came home: the ugly truth of the first world war’, The Guardian 10 November 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/news/2017/nov/10/how-colonial-violence-came-home-the-ugly-truth-of-the-first-world-war

Prabhat Patnaik, ‘Lenin, Imperialism, and the First World War’, Social Scientist, Vol. 42, No. 7/8 (July–August 2014).

Budheswar Pati, India and the First World War, Delhi 1996.

Vijay Prashad, The Death of the Nation and the Future of the Arab Revolution, Oakland 2016.

Sumit Sarkar, Modern India 1885-1947, Delhi 1983.