Vikas Rawal and Ankur Verma

.

The sudden imposition of a national lockdown to contain the spread of COVID-19 has impacted the agricultural sector in many different ways. Of these, the disruption in the functioning of the agricultural markets has been one of the most significant.

.

The lockdown was announced with little planning. Despite the fact that the rabi crops were being harvested or were about to be harvested in many parts of the country, the central government made no advance preparations to ensure that agricultural supply chains continued to function. It was only on March 27th, three days after the national lockdown and 5 days after the first round of restrictions (starting with janta curfew) that the government announced exemption of agricultural mandis from the restrictions of the lockdown.

.

However, despite the exemptions from the lockdown restrictions, absence of complementary measures to ensure the availability of labour, facilitate safe transportation of produce from villages to the mandis and taking measures to ensure safety of those involved in transportation and marketing continued to thwart normalisation of functioning of the mandis during the first phase of the COVID-19 lockdown.

.

This article, based on a recent study we conducted, presents quantitative evidence from 1331 mandis across the country to show that a large number of agricultural markets remained non-operational during the first phase of the lockdown, and in those markets that were operational, arrivals of key agricultural commodities fell very sharply. Our report, available at https://coronapolicyimpact.org, is the first quantitative assessment of the functioning of agricultural markets during the COVID-19 lockdown. The report is based on data on daily arrivals and prices from Agmarknet (http://www.agmarknet.gov.in/) for seven key rabi crops: wheat, chana, mustard, potato, onion, tomato and cauliflower.

.

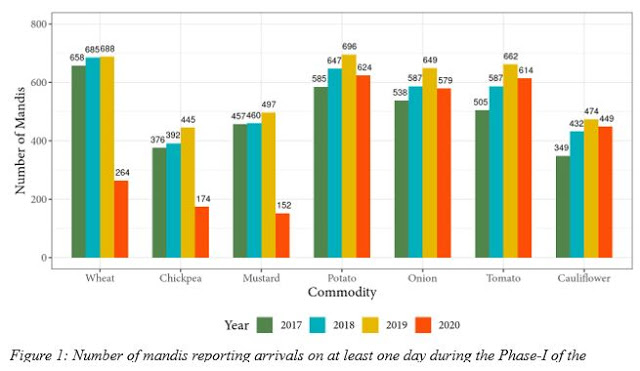

Figure 1 shows that a large number of mandis remained non-operational throughout the three-week period of the first phase of the lockdown. For example, wheat was sold in only 264 mandis during the period of lockdown in 2020 while in the same 21-day period in 2019, wheat was sold in 688 mandis. Chana was sold in only 174 mandis and mastard was sold in only 152 mandis during the first phase of the lockdown while they were sold in 445 and 497 mandis respectively during the same period in 2019. The situation was somewhat better in case of perishable crops though not all mandis where these crops were sold last year were functional during the period of the lockdown. In comparison with last year, number of mandis buying potato and onion fell by 70, number of mandis buying tomato fell by 48, and number of mandis where cauliflower was traded fell by 25. Of all the States covered in the data set, the problem of non-functional mandis was most severe in Madhya Pradesh, where only 43 out of 259 mandis were functional during the lockdown. Similarly, Only 57 out of 132 mandis in Rajasthan and only 34 out of 113 mandis in Gujarat were functional during the lockdown.

.

.

Our data also show clearly that, functioning under severe constraints, a large number of mandis limited their operations to only perishable commodities and did not have the capacity for marketing of grains. Of the 325 mandis where both grain and perishables were marketed between March 25 and April 14, 2019, only perishables were marketed in 100 mandis during the period of the lockdown. On the other hand, of the 449 mandis in which only grain was marketed during this period in 2019, 326 were non-functional during the period of the lockdown.

.

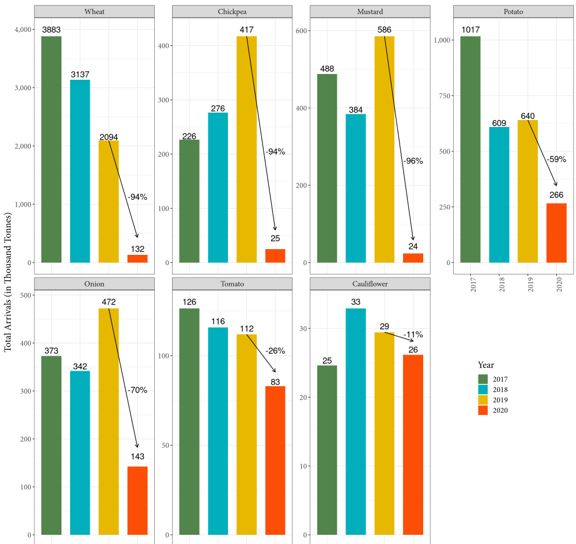

The data on arrivals show a sharp decline in the amount of crop produce that was sold in the mandis (Figure 2). For example, only 1.32 lakh tonnes of wheat was sold in the mandis during the period of the lockdown. This was only about 6 per cent of the total amount of wheat sold in the same 21-day period in 2019. Compared to the quantity sold in 2019, the arrivals in 2020 were also only 6 per cent for chana and 4 per cent for mustard.

.

It is important to note that very low arrivals of wheat during the period of the lockdown was not a result of delayed harvest in northern India. Harvest in northern India was delayed last year as well. In fact, as can be seen in Figure 2, the total arrivals of wheat between March 25 and April 14 last year was only 48 per cent of the arrivals during the same period in 2018. The low levels of wheat arrivals during the first phase of the lockdown this year was because of non-functioning mandis across central India where wheat is normally harvested before it is harvested in Punjab and Haryana.

.

Given that a large number of mandis shifted their focus to perishables, the situation in respect of these commodities was a little better. However, even among these crops, the drop in arrivals was very large for onions (70 per cent) and potato (59 per cent). The shortfall was lowest (11 per cent) in case of cauliflower. However, it needs to be pointed out that, in comparison with other crops considered in the study, quantity of production and sales of cauliflower are small. Even in 2019, the total arrivals of cauliflower during the 21-day period was only about 29 thousand tonnes.

.

Figure 2: Total arrivals of key food commodities in mandis, March 25-April 14, 2017-2020

.

While the extent of decline in quantity of arrivals was less in perishables than in grain, it must be noted that, even with this level of decline in marketing, a considerable amount of perishables would have remained unsold with farmers. Since these commodities are highly perishable, inability to sell the produce for a prolonged period is likely to have been resulted in a large part of the unsold crop getting damaged and thus losses on account of this are likely to have been substantial.

.

To sum, our analysis strongly suggests that, even though the agricultural markets were given exemptions from the lockdown restrictions, the lockdown resulted in a very severe contraction in the amount of crop produce that was sold in the mandis. The lack of prior preparation to ensure that agriculture and food systems are not disrupted is likely to have caused an immense distress to the peasantry for which the central government is squarely responsible.

.

Vikas Rawal and Ankur Verma are affiliated with the Centre for Economic Studies and Planning, JNU, New Delhi The detailed report on which this article is based can be seen at https://coronapolicyimpact.org/2020/04/22/agricultural-supply-chains-during-the-covid-19-lockdown/

.

Image Credit: People’s Archive of Rural India