A Reality Check on the Labour Market Flexibility Argument in India-Anamitra Roychowhury

The standard

arguments for undertaking labour market flexibility (LMF) in India are well

known. With the exception of few misleading media reports, that attribute the aggregate employment slowdown in India

(the phenomenon of ‘jobless growth’) to the so called labour market rigidities,

it is generally accepted even by the most ardent advocate of LMF that the

labour laws could not possibly be the

primary reason behind the recent employment debacle. This is simple to

understand. Since the vast majority of our workforce (92 per cent) is employed

in the unorganised sector, mostly falling outside the ambit of labour laws, it

is difficult to argue that the prime reason for aggregate employment stagnation

is due to the labour laws. Nonetheless, commentators are quick to point out

that the labour laws act as a barrier to ‘quality’employment generation in the

organised sector. Their basic argument is aptly summarized below: “Labour

market rigidities constrain growth in employment … In absence of flexible

labour markets in the organised sector (less than 8 per cent of the labour

force), growth in output does not necessarily lead to an increase in

employment, because labour effectively becomes a fixed input. Hence, production

becomes artificially capital intensive. In an attempt to protect existing jobs,

future and potential jobs are lost. Thus, the system is not in the broader

interests of labour either. In addition, labour legislation creates relatively

high wage islands in the organised sector and India’s comparative advantage in

an abundant supply of labour cannot be tapped … Conversely, the unorganized

sector (92 per cent of the labour force) has virtually no protection” (Debroy,

2005)

discussion it is clear that labour laws are identified to be the major reason

for the slow growth in employment in the organised sector. It is further

contemplated that the labour laws contribute to form a dual labour market,

producing a minute constituency of labour aristocracy at one end with a vast

majority of working paupers at the other. Therefore, to generate quality

employment and remove the distinction between formal and informal workers, it

is argued that India must introduce LMF. In what follows we shall examine the

validity of these claims.

legislation that has drawn maximum attention in the labour flexibility argument

is Chapter VB of the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947 (IDA). It stipulates that,

if an undertaking (engaged in manufacturing, mine and plantation activity)

employing 100 or more permanent workers wants to fire even one permanent

worker, then it has to obtain prior

permission from the government. This, it is argued, creates unnecessary

deterrence in quickly responding to the fluctuations faced in the product

market and makes the firm uncompetitive, thus hindering its capacity to

generate employment. This sentiment is

clearly reflected in the following: “In face of adverse shocks employers have

to reduce the workers’ strength; but they are not able to do so owing to the

existence of stringent job security provisions. On the other hand, when the

going is good and the economic circumstances are favourable, the firms may want

to hire new workers. But they would hire only when they would be able to

dispense with workers as and when they need to. Thus, separation benefits

accruing to workers become potential hiring costs for the employers. This

affects the ability and the willingness of firms to create jobs” (Sundar, 2005)

question arises, is it correct to ascribe the failure of the organised sector as a whole,

in generating formal jobs, primarily to the rigid labour laws? A close reading

of the domain of application of Chapter VB (IDA, 1947) reveals that it applies

to only manufacturing units, mines

and plantations – and not to firms

providing services or, related to agricultural activity. However, firms

employing 10 or more workers qualify for the ‘organised’ sector irrespective of their nature of activity

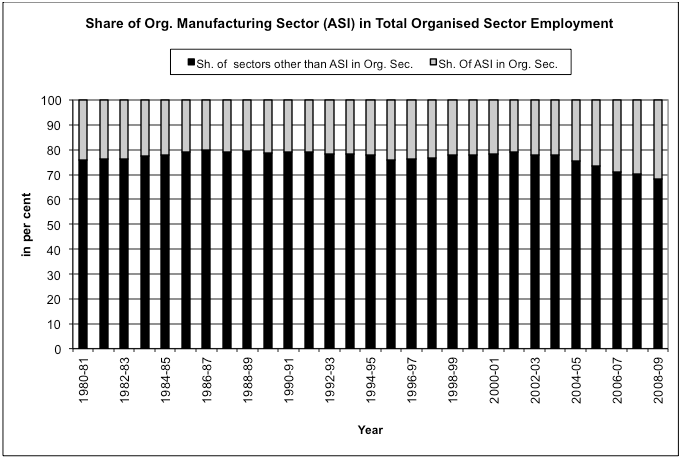

(Indian Labour Year Book, 2007 p.2). As figure 1 shows that the share of

organised manufacturing sector workers [where restriction on firing workers

applies; data obtained from Annual Survey of Industries (ASI)] in total organised workforce has been

persistently below 30 per cent for the whole period under study (except for the

last year, 2008-09).

Organised Manufacturing Sector from ASI, various years and Total Organised

sector employment data from DGET, various years.

the discussion just carried out it is clear that job security regulation

applies only to a subset of the total organised

sector namely, organised manufacturing sector (constituting less than 30 per

cent of total organised workforce) and does not extend to the organised

sector as a whole. Therefore, it is patently wrong to

identify the labour

laws for explaining the slowdown in employment growth of the overall

organised sector – since employment protection

laws apply to less than a third of

the total organised workforce, namely organised manufacturing sector.

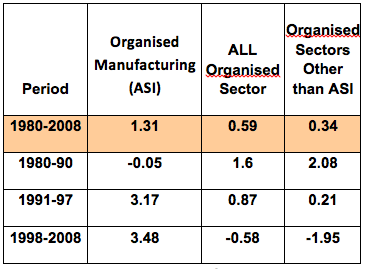

different segments of the total organised sector and compare it with the

organised manufacturing

sector. For this refer to table 1 below.

the Organised Sector (in per cent)

Same as figure 1

column depicts the growth rate of employment in the organised manufacturing

sector i.e. where labour laws apply. In the third column employment growth of

the organised sector as a whole (including organised manufacturing) is

calculated. Finally, the last column shows the growth rate of employment in the

organised segment (excluding organised manufacturing). It is easy to see from

the table that in the long time period [i.e. 1980-2008] the employment growth

in organised manufacturing sector (where labour law applies) is greater than both the organised sector

as a whole, as well as, the section of organised segment other than organised

manufacturing. This holds true for the sub-period analysis except for the

sub-period 1980-1990[1].

Thus, it may be concluded that the organised manufacturing sector (where the

law stipulates firms to take prior permission for firing) actually boosted the

employment growth in the overall

organised sector (other than the sub-period 1980-1990) rather than pulling it

down. Thus, there is little evidence to suggest that the slowdown in employment

growth in the organised sector as a whole

was due to the labour laws. [Sluggish growth in overall organised sector employment is actually explained by the failure of the public sector to generate

formal jobs – a direct fallout of the conscious policy decision by the State.

In fact there is also evidence on employment growth being higher in those segments of organised

manufacturing where labour laws apply compared to where it does not apply (for a discussion on these issues see

Roychowdhury, 2013)].

the question, whether labour laws produce duality in the labour market by

creating a small group of labour aristocracy located within a vast pool of

informal workers. The basic argument is quite simple – labour laws by extending

protection of employment increases the bargaining power of workers, which in

turn is utilized by them to jack up wages. As Ghose (1994) puts it – “A popular

perception in India today is that rising labour costs [i.e. wages], [are]

attributable to labour market rigidities generated by inappropriate [labour]

regulations …”. On the other hand, since informal workers are not protected by

labour laws – their wages remain low. Note that in this argument one section of

worker is pitted against another section; with an attempt to deviate our

attention from the class distribution of income.

armed with employment protective legislation, could raise their wages due to

enhanced bargaining power then we would expect the share of wages in total

output [gross value added (GVA)]to progressively rise overtime. However, from

figure 2 it is clear that the available evidence is at odds to substantiate

such a claim. There is almost a secular decline in the share of wages to output

– in fact the wage share in organised manufacturing has come down to less than

10 per cent in the most recent years. So, if wage share is taken as an

indicator of the relative bargaining position of labour vis-à-vis capital – it

is clear that the bargaining of the workers weakened over time, even in a

sector where labour is statutorily protected by law. To be sure, workers in the informal sector

might have received an even more raw deal, but the whole point is the position

of the organised manufacturing workers deteriorated as well. By no means can

the organised manufacturing workers (with a wage share of less than 10 per cent

of GVA) be demarcated to constitute a labour aristocracy.

little further. There is evidence of increase in informal employment within the organised manufacturing

sector. Remember, the law requiring prior permission from the government for

carrying out retrenchment and layoff applies only to permanent workers and not to the workers employed through

contractors (contract workers). And we find that the share of contract workers

in total workers has increased consistently over time (figure 3). By now it is

one-third of the organised manufacturing employment – precisely the sector

where labour law applies. Thus, any claim of labour aristocracy in midst of

rising informal employment is premature.

advanced in favour of LMF can be logically sustained. Nonetheless, undertaking

LMF has far reaching implications. It is easy to see that the demand for labour

flexibility, by invoking the labour aristocracy argument is actually a strategy

to divide the working population. By inventing the conflict of interest among

different segments of the working population, LMF actually wants to further the

interests of capital vis-à-vis labour as

a whole. In fact to introduce LMF for rapid growth in ‘quality’ employment

is a contradiction in terms; this is so for once LMF is introduced, ‘quality’

itself is degraded. Similarly, appealing to the labour aristocracy argument is

inverted logic; if a small section of working population is better off than the

vast majority of the working poor, then in the quest for obtaining a

homogeneous workforce, we must search for strategies to improve the conditions

of the informal workers rather than worsening the position of the formal

workers.

and P.D. Kaushik, ed., Reforming The

Labour Market (New Delhi:

Academic Foundation).

in Organised Manufacturing in India’,

The Indian Journal of Labour Economics, Vol. 37 No. 2: 143-162.

Government of India.

Market Flexibility and Conditions of Labour in the Era of Globalisation: The

Indian Experience, unpublished Ph.D thesis submitted to Jawaharlal Nehru

University, New Delhi.

Comprehensive Review and Some Suggestions’, Economic and Political Weekly,

May 28: 2274-2285.

faculty of Economics at St. Stephen’s College, New Delhi.

employment in the sub-period 1980-1990 is not

due to labour laws but the way ASI enumerates workers and the underlying nature of technical progress (notably

labour saving variety). For details see Roychowdhury (2013).