Union Budget 2014-15 and the Myth of UPA’s ‘Populism’ — Surajit Mazumdar

The Union Budget 2014-15 presented by the

Finance Minister before Parliament on 17th February this year was

the last budget to be presented in the 10 years of UPA rule.

General elections

being round the corner no significant new measures were to be taken in this

budget – that had to be left to the new Lok Sabha and government, in whose term

would fall the major part of the coming financial year 2014-15 (1 April 2014 to

31 March 2015). However, the budget accounts were still significant because of

what they revealed about the developments in the year coming to an end on 31

March 2014. For the second successive year, the revised estimates of total Central

Government expenditures for 2013-14 were lower than what had been budgeted before

the year started. The same had not only happened last year, the actual final

figure of expenditure 2012-13 turned out to be even less than the revised

estimates, at the time Union Budget 2013-14 was presented! The fiscal deficit

to GDP ratios in these two years, at 4.9 and 4.6 per cent respectively, were

also at their lowest levels in the period since UPA 2 assumed office.

back in the last two years flies in the face of theories of ‘political budget

cycles’ which predict that governments tend to become ‘populist’ and profligate

as elections approach. The real profligacy of the UPA government has been only

in their claims of how much they have done for the ‘aam aadmi’ and for the

development of the country. When it has come to putting money to back its talk,

it has been stingy as hell. In such circumstances, the hue and cry from certain

quarters about how the UPA’s populism has destroyed the fiscal climate – seen

recently most notably in the context of the National Food Security Act – might

appear bizarre. Most people making such charges are also rooting for a Narendra

Modi led government to put the Indian economy back on track. What is really behind

this?

The UPA’s Record: Ten Years of Fiscal Parsimony

tenets of neoliberalism. While maintaining a low fiscal deficit (the excess of

expenditures over revenues of government) is one of the important objectives of

conservative fiscal policy it is equally important for this to be achieved

while keeping taxes low. For this combination to be possible, government

expenditure must also be kept within limits.

by the Indian state since 1991, when Manmohan Singh was Finance Minister, also

elevated fiscal conservatism to the status of the ruling dogma guiding fiscal

policy. Every government since then has

paid obeisance to it. One of the first acts of the UPA 1 Government signalling

its commitment to it was the notification of the Fiscal Responsibility and

Budget management (FRBM) Act passed by its predecessor Government. Its

consistent adherence since then to the policy of keeping government expenditure

in check is exemplified by the levels of the Central Government Expenditure to

GDP ratio in the ten years of UPA rule (Table 1). This ratio, a measure of the

Central Government’s share in the total annual expenditure of the economy, has

through this period been kept below the level at the end of the Vajpayee led

NDA government’s term (which itself was below the pre-1991 level). Of course,

capital expenditure or public investment has faced a significant share of the

squeeze in UPA’s times. It may be worthwhile remembering that this is in a

background where public expenditure levels in India are very low when compared

to both developed as well as developing countries.

Expenditure as Percentage of GDP at Market Prices

Central Government Expenditure to GDP but its actual levels adjusted for

inflation (i.e. real expenditure), then the following picture emerges (summarized

in Figure 1). The first two years of UPA 1 saw a pretty severe expenditure

squeeze – the average annual real Central Government expenditures in 2004-05

and 2005-06 were below 2003-04 levels. Then followed a period lasting till 2010-11

during which expenditure in real terms grew pretty rapidly. A slowdown in the

pace of that growth began in 2010-11 itself, and in the last three years real

expenditure has virtually completely stagnated. In other words, in half the

ten-year period that UPA has been in power – made up of the first two and the

last three years of its rule – Central Government expenditures have remained

completely frozen. It is only in the remaining half in between the two ends

that expenditures increased.

Growth of Central Government Expenditure at Constant 2004-05 prices

order to understand how the increase of Central Government expenditure in the

period from 2006-07 to 2011-12 was consistent with adherence to fiscal

conservatism one needs to appreciate the following facts:

Till the global crisis erupted,

the Indian economy for a five year period beginning in 2003-04 experienced very

high and also extremely inegalitarian growth. Corporate profits as well as

high-end incomes grew extremely rapidly. As a result of the rising share of

such incomes in total income generated by the Indian economy, and not because

of any increase in tax rates, the tax to GDP ratio also increased as can be

seen in Table 2. Corporate taxes alone accounted for over 55 per cent of the

increase in the tax-GDP ratio between 2003-04 and 2007-08. While some part of

the Corporate and other income taxes were transferred to the states, the

Central Government revenue situation also improved dramatically. As a result,

expenditures could be stepped up even without reversing the trend of decline in

the fiscal deficit-GDP ratio and it is only within those limits that it was increased.

Indeed, in 2007-08 the fiscal deficit to GDP ratio at 2.5 per cent was at its

lowest level since 1991.

The last year of the UPA 1 term

saw the outbreak of the global crisis in response to which ‘fiscal stimuli’

became the flavour of the season the world over for a period of time. Even the

staunchest of fiscal conservatives did not object to the initial stimuli though

eventually the rising deficits and debt of governments led to a clarion call

for ‘austerity’ measures whose effects are being faced by people across the

world. India under UPA followed the same

course of a fiscal stimulus followed by a retreat from it. The stimulus meant

that government expenditure growth was maintained for some time even after

2007-08. However, the major component of the stimulus took the form of tax

concessions – typical of conservative fiscal policy. As a result, the tax to

GDP ratio plummeted (see Table 2) and this more than any increase in the

expenditure to GDP ratio led to a sharp rise in the fiscal deficit-GDP ratio.

The retreat from the stimulus, or

‘fiscal consolidation’, has been the dominant fiscal policy concern for most of

UPA 2’s term. In contrast to what happened during the stimulus, however, in the

retreat the curbing of government expenditure was clearly prioritized over tax

mobilisation. Partly

the result of this was the slowdown in growth in the last few years, which has

intensified the revenue constraints. Tax-GDP ratios have thus remained

lower than they were in 2007-08 while expenditures have been curbed to reduce

the fiscal deficit. This contrast is exemplified by what is visible in the last

two rows of Table 2. From 2007-08 to 2009-10, the central government

expenditure to GDP ratio increased less than the parallel decline in tax to GDP

ratios. However, while that increase has been more than undone by 2013-14, the

tax-GDP ratios have recovered by only a fourth or less of their fall.

Expenditure, Tax Revenue and Fiscal Deficit as Percentages of GDP at Current

Market Prices

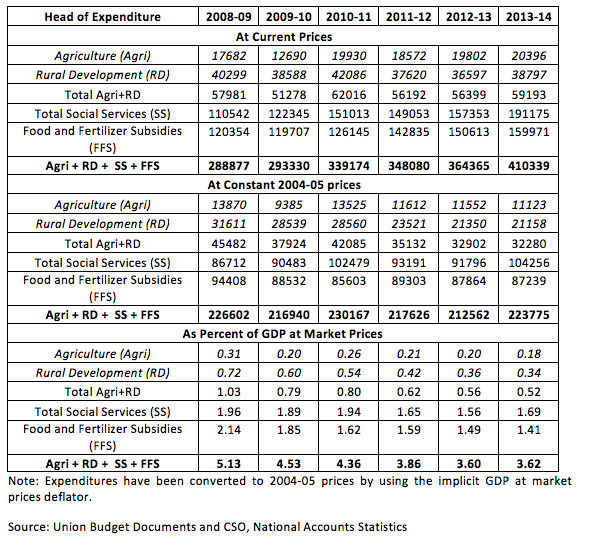

Since there is so much talk about

populism, it is also instructive to see the expenditure heads that have been

hit most by austerity measures. As is starkly visible in Table 3, the

cornerstone of the expenditure control strategy has been cuts or restraints in precisely

those expenditures with an important bearing on the lives of people – agriculture

and rural development; fertilizer and food subsidies; and social services

(under which come areas like health and education). In real terms the

expenditure on these heads has been lower throughout the five years of UPA 2

than in the last year of UPA 1. The expenditure on rural development (which

includes the MNREGA) has even in nominal terms been lower in the years

thereafter than in 2008-09!

Expenditure (Plan and Non-Plan) on Agriculture, Rural Development, Social

Services and Food and Fertilizer Subsidies

Why is a Myth being Propagated?

criticized for its subterfuge – for claiming what it has not done. Like the

BJP’s Shining India campaign came flat in the 2004 elections, the people who

have experience the reality of its policies are unlikely to buy the UPA’s

claims no matter how much the statistics are juggled. The so-called ‘populism’

of the UPA will not be visible to them. However, the ‘critics’ of the UPA who

are accusing it of fiscal recklessness are somehow managing to see what neither

the statistics nor actual experience on the ground shows to be true –a

government splurging crores of rupees on schemes bringing short-term benefits

to millions of voters. These critics are certainly not people who are

illiterate about money matters. On the contrary their singular obsession is

with the process of making more and more money – the variety among them ranging

from those who engage in scholarly ‘study’ of that process to those actually

participating in it. Surely such people cannot be ignorant of the real picture.

So then why do they say what they say?

were initiated have seen extreme economic polarization of an order not seen

before in the period since independence. While the majority of Indians have

been condemned to income stagnation and depression, a few large corporate

houses and a rich upper-income segment have increased their stranglehold on the

country’s income and wealth. In this they have been aided by the process of opening

up of the Indian economy to foreign capital. Fiscal conservatism has been an

able servant to this massive concentration and accumulation which has only

whetted the appetite of its beneficiaries rather than satiated them. They are

therefore greedy for more of the same even as the regime now faces a crisis

both domestically and at the global level as a result of its own

contradictions.

their way out of the crisis by trampling even more on the interests of the rest

– they would like more tax concessions for themselves; more handing over of

national assets to them at low prices; more expenditure out of shrinking

government revenues on the roads, highways and flyovers they need; and yet

fiscal deficits to be kept low so that foreign investors are not scared away.

The critics of the UPA’s ‘populism’ are simply the conscious or unconscious

spokespeople of this desire. What they are in effect saying is that the UPA has not done enough,

meaning not been savage enough, on the expenditure compression front because of

electoral compulsions. They are hoping that Narendra Modi can benefit from the

discontent generated by the UPA’s ‘success’ in hurting the interests of the

Indian people to do an even better job of the same! After all, he has a proven

track record of knowing how the politics that takes human lives can be used to

further the economics of high human cost.

For the time being, therefore, the only useful purpose that the UPA can

serve for its true masters is to be the butt of their criticisms about ‘loose

purse strings’ so that the appropriate climate is created for the

belt-tightening to be imposed after the elections on those who in any case have

very little.

Mazumdar is Associate Professor at Ambedkar University Delhi