There is no doubt that the newly elected government will

favour deregulating the price of diesel as well as other petroleum products in lieu of subsidies or grants to the

oil sector. At least on this issue both governments (NDA as well as UPA) are of

the same view, despite the fact that under-recovery on diesel touched record

low at Rs 2.80 per litre on 2nd of June ’14 .(www.pib.nic.in).

favour deregulating the price of diesel as well as other petroleum products in lieu of subsidies or grants to the

oil sector. At least on this issue both governments (NDA as well as UPA) are of

the same view, despite the fact that under-recovery on diesel touched record

low at Rs 2.80 per litre on 2nd of June ’14 .(www.pib.nic.in).

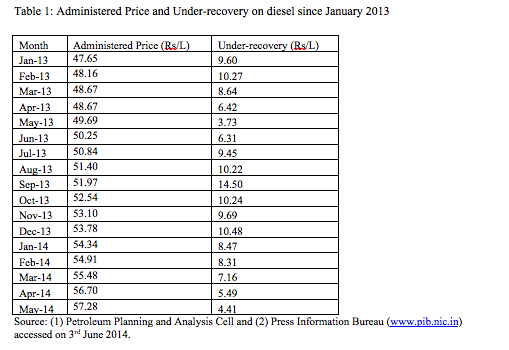

Since

January 2013, Oil Marketing Companies (OMCs) were allowed to increase the price

of diesel by 40-50 paisa per month on until under-recovery on diesel vanishes completely.

It is postulated that in coming few months the diesel price will be left open

to free market if the same pricing trend continues and other macro indicators

do not change. This article focuses on two aspects- first; the validity of

arguments which favour price deregulation of petroleum products and the second;

the possible gains and losses of such an outcome.

January 2013, Oil Marketing Companies (OMCs) were allowed to increase the price

of diesel by 40-50 paisa per month on until under-recovery on diesel vanishes completely.

It is postulated that in coming few months the diesel price will be left open

to free market if the same pricing trend continues and other macro indicators

do not change. This article focuses on two aspects- first; the validity of

arguments which favour price deregulation of petroleum products and the second;

the possible gains and losses of such an outcome.

Deregulation is promulgated in response

to huge losses made by OMCs or “under –recovery” faced by the oil-sector and as

a result of these the government is facing added fiscal burden. – How far this is true?

to huge losses made by OMCs or “under –recovery” faced by the oil-sector and as

a result of these the government is facing added fiscal burden. – How far this is true?

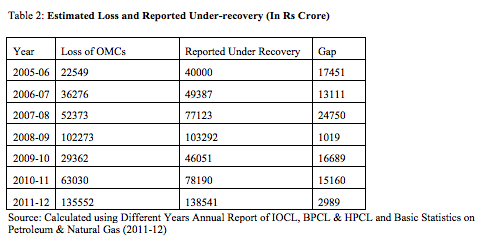

“Under-recovery” is not congruent to loss

(Sethi, 2010, and Dasguta & Chatterjee, 2012). It is the gap between

desired price and administered price. Apart from the actual cost, desired price

includes many other elements like cost & freight charges, import and custom

duties etc. which just inflate desired price and, in turn, produce “under-recovery”.

These factors amount to overestimating the actual loss, given the fact that

India doesn’t import petroleum products but only crude-oil. In fact India’s

refining capacity of crude oil is more than its domestic demand and is exported.

Because of this over-estimation, under-recovery is cited as ‘loss’. Reported

under-recovery is far greater than the actual loss. Apart from 2008-09 and

2011-12, the average gap between under-recovery and loss has been around Rs

17000 crore.

(Sethi, 2010, and Dasguta & Chatterjee, 2012). It is the gap between

desired price and administered price. Apart from the actual cost, desired price

includes many other elements like cost & freight charges, import and custom

duties etc. which just inflate desired price and, in turn, produce “under-recovery”.

These factors amount to overestimating the actual loss, given the fact that

India doesn’t import petroleum products but only crude-oil. In fact India’s

refining capacity of crude oil is more than its domestic demand and is exported.

Because of this over-estimation, under-recovery is cited as ‘loss’. Reported

under-recovery is far greater than the actual loss. Apart from 2008-09 and

2011-12, the average gap between under-recovery and loss has been around Rs

17000 crore.

As far as

questions of financing under-recovery are concerned, almost 50% of it is absorbed

within the sector and remaining 50% is financed by government.

Another interesting point worth noting is

regarding, how the “loss” is understood. For this we need to understand the

structure of the oil-sector. There are 14 Public Sector Under-takings (PSUs)

under the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas. Out of these, six of them are

involved in major businesses. On the basis of their financial performance, these

6 companies are further classified as up-stream and down-stream companies.

ONGC, GAIL and OIL are up-stream companies. Their prime businesses involves

extraction and purchase of crude oil (ONGC also undertakes refining but its

share in the total is very small). IOCL, BPCL and HPCL are down-stream

companies involved mainly in refining and retailing (IOCL also purchases crude

but its share is very small).

regarding, how the “loss” is understood. For this we need to understand the

structure of the oil-sector. There are 14 Public Sector Under-takings (PSUs)

under the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas. Out of these, six of them are

involved in major businesses. On the basis of their financial performance, these

6 companies are further classified as up-stream and down-stream companies.

ONGC, GAIL and OIL are up-stream companies. Their prime businesses involves

extraction and purchase of crude oil (ONGC also undertakes refining but its

share in the total is very small). IOCL, BPCL and HPCL are down-stream

companies involved mainly in refining and retailing (IOCL also purchases crude

but its share is very small).

The

down-stream companies are the loss making bodies in the oil-sector. But there

are no documentary estimates of actual loss. So by looking at the profit and

loss accounts of these three retail units and by taking into consideration the

external elements we can arrive at a figure of loss which is different from the

claimed under-recovery. There are three external elements in the profit &

loss account – grants by government, subsidy as per scheme, and discount by

up-stream companies. Grants are given to down-stream companies against their

claim of under-recovery. Since June 2010, there has been no under-recovery on

petrol. In the case of diesel, partial deregulation is allowed (as mentioned

above) since January. Only two petroleum products i.e. PDS kerosene and LPG have

not yet witnessed any deregulation in their prices till now (but there is a

limitation on number of subsidised LPG supplied to households). Subsidy as per

scheme is also given to down-stream companies only for these two products.

Other than the government a part of under-recovery is also financed by

up-stream companies in terms of discounts on crude-oil prices.

down-stream companies are the loss making bodies in the oil-sector. But there

are no documentary estimates of actual loss. So by looking at the profit and

loss accounts of these three retail units and by taking into consideration the

external elements we can arrive at a figure of loss which is different from the

claimed under-recovery. There are three external elements in the profit &

loss account – grants by government, subsidy as per scheme, and discount by

up-stream companies. Grants are given to down-stream companies against their

claim of under-recovery. Since June 2010, there has been no under-recovery on

petrol. In the case of diesel, partial deregulation is allowed (as mentioned

above) since January. Only two petroleum products i.e. PDS kerosene and LPG have

not yet witnessed any deregulation in their prices till now (but there is a

limitation on number of subsidised LPG supplied to households). Subsidy as per

scheme is also given to down-stream companies only for these two products.

Other than the government a part of under-recovery is also financed by

up-stream companies in terms of discounts on crude-oil prices.

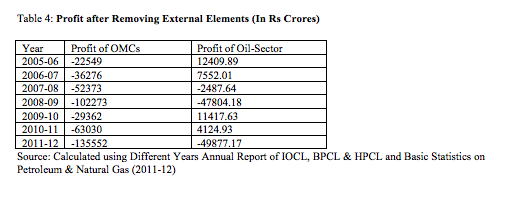

Now it is

true that if we remove all these three external elements of financing

under-recovery then the profit of down-stream companies turns out to be

negative i.e. IOCL, BPCL and HPCL are making losses. Here three important

points need to be noted.

true that if we remove all these three external elements of financing

under-recovery then the profit of down-stream companies turns out to be

negative i.e. IOCL, BPCL and HPCL are making losses. Here three important

points need to be noted.

1. Product-wise

disaggregation of cost of production is impossible since the refining process

is very complicated. Actually different products are recovered at different

levels of the same production process. So any claim of product specific loss

has always some degree of imperfection.

disaggregation of cost of production is impossible since the refining process

is very complicated. Actually different products are recovered at different

levels of the same production process. So any claim of product specific loss

has always some degree of imperfection.

2. Since

product specific loss calculation is almost impossible, we have to look at

aggregate loss. For this purpose we need to look at the whole production

process. IOCL, BPCL and HPCL primarily refine crude oil and sell it to

retailers. Here we need to be cautious as production process of petroleum

products doesn’t start from refining but from extraction of crude. So any

calculation of aggregate loss must include the whole production process. India

imports around 80% of its crude oil demand and the rest is extracted

domestically. So in the Indian case 80% of the production process starts from

importing crude oil and the rest 20% from extraction. For the purpose of

arriving at a figure of aggregate loss we have to include all companies of the

oil-sector. After adding these, loss vanishes and we find that in fact the oil-

sector as a whole earns profits, even with the present structure of taxes and

duties, for most of the time, in last seven years.

product specific loss calculation is almost impossible, we have to look at

aggregate loss. For this purpose we need to look at the whole production

process. IOCL, BPCL and HPCL primarily refine crude oil and sell it to

retailers. Here we need to be cautious as production process of petroleum

products doesn’t start from refining but from extraction of crude. So any

calculation of aggregate loss must include the whole production process. India

imports around 80% of its crude oil demand and the rest is extracted

domestically. So in the Indian case 80% of the production process starts from

importing crude oil and the rest 20% from extraction. For the purpose of

arriving at a figure of aggregate loss we have to include all companies of the

oil-sector. After adding these, loss vanishes and we find that in fact the oil-

sector as a whole earns profits, even with the present structure of taxes and

duties, for most of the time, in last seven years.

Even

if we consider the loss of OMCs, there should still be some analysis of the

government’s claim of fiscal burden. Here we should note that Tax+Duties earned

by the government (central as well as state, although states’ share is very

small) from the Oil-Sector is far greater than the under-recoveries and

subsidies (Sethi, 2010) and through the same way government earns huge revenue

from OMCs as well. So the claim that the government is facing a huge fiscal

burden is wrong.

if we consider the loss of OMCs, there should still be some analysis of the

government’s claim of fiscal burden. Here we should note that Tax+Duties earned

by the government (central as well as state, although states’ share is very

small) from the Oil-Sector is far greater than the under-recoveries and

subsidies (Sethi, 2010) and through the same way government earns huge revenue

from OMCs as well. So the claim that the government is facing a huge fiscal

burden is wrong.

Almost

half of the under-recovery is financed by government of India so it is possible

that post deregulation, government exchequer will save some money. The

remaining half of the burden is shared by up-stream companies so these

companies will also get rid of this “so called” burden and finally some part of

the burden is absorbed by OMCs, henceforth after complete removal of under

recovery these companies need not to do so. Apart from these, OMCs will also

get rid of cash flow problem, which is caused by delay in payment by

government. But the above benefit can’t be said significant as part of under

recovery shared by up-stream companies is very small in comparison to its

profit and that’s why for most of the year even after absorbing this cost,

sector as a whole makes profit. A similar argument could be constructed for

government as amount incurred for financing under recovery is very small in

comparison of what government gets from the sector or OMCs in form of taxes,

duties and royalties.

half of the under-recovery is financed by government of India so it is possible

that post deregulation, government exchequer will save some money. The

remaining half of the burden is shared by up-stream companies so these

companies will also get rid of this “so called” burden and finally some part of

the burden is absorbed by OMCs, henceforth after complete removal of under

recovery these companies need not to do so. Apart from these, OMCs will also

get rid of cash flow problem, which is caused by delay in payment by

government. But the above benefit can’t be said significant as part of under

recovery shared by up-stream companies is very small in comparison to its

profit and that’s why for most of the year even after absorbing this cost,

sector as a whole makes profit. A similar argument could be constructed for

government as amount incurred for financing under recovery is very small in

comparison of what government gets from the sector or OMCs in form of taxes,

duties and royalties.

Then the

questions arise, if government or oil-sector is not going to be benefited

appreciably then who are going to be possible beneficiary from this move and on

what cost?

questions arise, if government or oil-sector is not going to be benefited

appreciably then who are going to be possible beneficiary from this move and on

what cost?

Apart

from the PSUs there are some private players engaged in retail business. Essar

and Reliance are two big names in this area. Currently Essar has 1400

operational retail outlets and also ready to add 1600 more (Business Standard

Oct. 2013). Reliance has currently 1450 retail outlets out of which 280 are

operational at present. Given their potential they can enter and expand their

retail business after complete removal of under-recovery. These private

companies have also huge refining capacity. Essar and Reliance account for 80

Million Metric Tonne Per Annum (MMTPA) out of 215.07 MMTPA of all India

including PSUs and joint venture i.e. around 37% (Refinery Map of India, PPAC).

Currently Reliance and Essar are primarily exporting petroleum products but

after price deregulation selling in the domestic market would be easier.

from the PSUs there are some private players engaged in retail business. Essar

and Reliance are two big names in this area. Currently Essar has 1400

operational retail outlets and also ready to add 1600 more (Business Standard

Oct. 2013). Reliance has currently 1450 retail outlets out of which 280 are

operational at present. Given their potential they can enter and expand their

retail business after complete removal of under-recovery. These private

companies have also huge refining capacity. Essar and Reliance account for 80

Million Metric Tonne Per Annum (MMTPA) out of 215.07 MMTPA of all India

including PSUs and joint venture i.e. around 37% (Refinery Map of India, PPAC).

Currently Reliance and Essar are primarily exporting petroleum products but

after price deregulation selling in the domestic market would be easier.

This

policy move will help private players to capture a significant portion of

market which is currently in PSUs hands on one hand and on the flip side this

will influence common man’s budget, with inflation on course (Patnaik, 2011). The

stake of balance between powers is such that the newly elected government would

definitely ensure the interest lies with the former.

policy move will help private players to capture a significant portion of

market which is currently in PSUs hands on one hand and on the flip side this

will influence common man’s budget, with inflation on course (Patnaik, 2011). The

stake of balance between powers is such that the newly elected government would

definitely ensure the interest lies with the former.

References:

Dasgupta,

Dipankar and T. K. Chatterjee (2012): “Petroleum Pricing Policy: A Viable

Alternative”, Economic and Political

Weekly, Vol. XLVII No. 46

Dipankar and T. K. Chatterjee (2012): “Petroleum Pricing Policy: A Viable

Alternative”, Economic and Political

Weekly, Vol. XLVII No. 46

Patnaik,

Prabhat (2011): “Raising Price to Curb Inflation”, People’s Democracy, Vol. XXXV No. 29

Prabhat (2011): “Raising Price to Curb Inflation”, People’s Democracy, Vol. XXXV No. 29

Sethi,

Surya P. (2010): “Analysing the Parikh Committee Report on Pricing of Petroleum

Products”, Economic and Political Weekly,

Vol XLV No. 13

Surya P. (2010): “Analysing the Parikh Committee Report on Pricing of Petroleum

Products”, Economic and Political Weekly,

Vol XLV No. 13

Business

Standard (July 2nd 2012): “RIL to reopen 50 fuel pumps in Gujarat” http://www.business-standard.com/article/companies/ril-to-reopen-50-fuel-pumps-in-gujarat-112070200058_1.html

Standard (July 2nd 2012): “RIL to reopen 50 fuel pumps in Gujarat” http://www.business-standard.com/article/companies/ril-to-reopen-50-fuel-pumps-in-gujarat-112070200058_1.html

Business

Standard (October 18th 2013): “Diesel decontrol hope puts Essar in

high gear on fuel retail” http://www.business-standard.com/article/companies/diesel-decontrol-hope-puts-essar-in-high-gear-on-fuel-retail-113101700829_1.html

Standard (October 18th 2013): “Diesel decontrol hope puts Essar in

high gear on fuel retail” http://www.business-standard.com/article/companies/diesel-decontrol-hope-puts-essar-in-high-gear-on-fuel-retail-113101700829_1.html

Manish

Kumar (manish14jnu@gmail.com) & Surobhi Mukherjee (007surobhi@gmail.com) are M. Phil research scholars at

Centre for Economic Studies and Planning, Jawaharlal Nehru University.

Kumar (manish14jnu@gmail.com) & Surobhi Mukherjee (007surobhi@gmail.com) are M. Phil research scholars at

Centre for Economic Studies and Planning, Jawaharlal Nehru University.