Rahul Vaidya

Amidst the manufactured fury and ‘josh’ of cinematic jingo-nationalist glory all

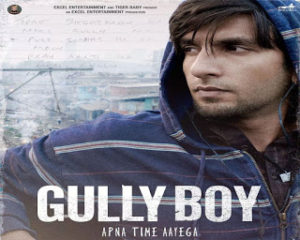

Amidst the manufactured fury and ‘josh’ of cinematic jingo-nationalist glory allthrough January (‘Uri’, ‘Thackeray’, ‘The Accidental Prime Minister’) and then

somber moment of Pulwama terrorist attacks and counter (surgical) strikes being

turned to new levels of political frenzy; was the recent release and commercial

success of Hindi film ‘Gully Boy’ (directed by acclaimed director Zoya Akhtar).

No wonder that remarkable success of

this film did little to shape the public conversation at large. The film which

takes on serious issues of class, urban ghettos, patriarchy, and

counter-cultural forms of expressions of the underground in a serious manner

and gravitas was clearly at odds with cheer-leading Hindu Majoritarian consumer

middle class mobs that matter for box offices. Cinematic critical acclaim and

commercial success aside, this film deserves a larger conversation and debate

and here is my attempt to pen down a few thoughts in this regard.

At

the outset, ‘Gully Boy’ is a classic underdog, rags to riches story. Murad

(Ranveer Singh) is a final year college student staying in Dharavi slum with

his dysfunctional family. His driver father is abusive and keeps everyone on

their toes, he fights with Murad and his mother and has got a second wife.

Amidst all the chaos and harsh poverty; Murad has some fine support from his

girlfriend Safeena (Alia Bhatt) who is feisty and comes from well-off family

with her father a doctor. And of course, he has poetry and rap music. As with

rappers all around, another rapper MC Sher (Siddhant Chaturvedi) takes him

under his wings, shares the techniques and tricks of the trade and fighting all

hardships and abyss of bleak future of car stealing, mechanic, AC repairing,

drug dealing etc. that is staring in the face; Murad goes on to discover his

‘self’, his identity as ‘artist’ and of course winning contest, popularity, and

money.

the outset, ‘Gully Boy’ is a classic underdog, rags to riches story. Murad

(Ranveer Singh) is a final year college student staying in Dharavi slum with

his dysfunctional family. His driver father is abusive and keeps everyone on

their toes, he fights with Murad and his mother and has got a second wife.

Amidst all the chaos and harsh poverty; Murad has some fine support from his

girlfriend Safeena (Alia Bhatt) who is feisty and comes from well-off family

with her father a doctor. And of course, he has poetry and rap music. As with

rappers all around, another rapper MC Sher (Siddhant Chaturvedi) takes him

under his wings, shares the techniques and tricks of the trade and fighting all

hardships and abyss of bleak future of car stealing, mechanic, AC repairing,

drug dealing etc. that is staring in the face; Murad goes on to discover his

‘self’, his identity as ‘artist’ and of course winning contest, popularity, and

money.

No

wonder that aspiring middle class, youth would identify with ‘Gully Boy’ which ends

on the promise and confident proclamation of ‘apna time aayega’. Some

commentators have criticized the film as ‘a markedly neo-liberal moment in

Bollywood’[1] which

fails to appreciate the crux of hip hop that is identity and harsh reality of

urban ghetto life. The film fails to track political roots of the hip hop as

protest music against discrimination and ghettoisation. Further, the rap songs

in the film – ‘Jingostan’ and ‘Azadi’ (JNU protests) are poignant but they are

stripped of the specific context and rappers’ reaction to it[2].

Apart from this, there has been criticism that how despite trying to distance

itself from exoticising poverty, Dharavi etc., the film ends up doing exactly

that.

wonder that aspiring middle class, youth would identify with ‘Gully Boy’ which ends

on the promise and confident proclamation of ‘apna time aayega’. Some

commentators have criticized the film as ‘a markedly neo-liberal moment in

Bollywood’[1] which

fails to appreciate the crux of hip hop that is identity and harsh reality of

urban ghetto life. The film fails to track political roots of the hip hop as

protest music against discrimination and ghettoisation. Further, the rap songs

in the film – ‘Jingostan’ and ‘Azadi’ (JNU protests) are poignant but they are

stripped of the specific context and rappers’ reaction to it[2].

Apart from this, there has been criticism that how despite trying to distance

itself from exoticising poverty, Dharavi etc., the film ends up doing exactly

that.

I

would like to argue that this criticism misses something critical that is at

heart at this film (and Zoya Akhtar’s other films as well)- here’s a film maker

which goes about her work not in a straightforward but in a layered fashion and

treats the familiar tropes not just with sensibility and sensitivity but also deception

and cunning grounded in realism. It is quite easy to miss the subtle elements in works such as

this, and to only list out the usual offenses of commercial Hindi Bollywood.

would like to argue that this criticism misses something critical that is at

heart at this film (and Zoya Akhtar’s other films as well)- here’s a film maker

which goes about her work not in a straightforward but in a layered fashion and

treats the familiar tropes not just with sensibility and sensitivity but also deception

and cunning grounded in realism. It is quite easy to miss the subtle elements in works such as

this, and to only list out the usual offenses of commercial Hindi Bollywood.

That

class is central to the film is accepted by everyone including critics. So what

is it that requires our attention? That the ‘underdog’ story here doesn’t go

along the lines of ‘angry young man’ themes of Bollywood is as much recognition

of reality of 30 years of neo-liberal reforms and the shift in politics as well

as identity of ‘working class’ as we understand and not only a political choice

of playing to the gallery of aspiring middle class. If anything, it is

important to underline that even ‘angry young man’ was also a trope with which

cinema-going middle class of the 70s identified with and hence was as much an

effort to play to the gallery if not more. What is more, that image of ‘angry

young man’ (intricately linked to Amitabh Bacchan) had firm ground in upper

caste, middle- lower middle class imagination of seeing oneself as savior,

taking on the dirty world of mafia, corruption, politicians, worshipping

‘mother’ while displaying a nihilistic ethic otherwise. There was a cathartic

pleasure involved in seeing ‘angry young man’ do the dirty job for you on

screen while speaking language of authority and power. This language was

captivating. It was poetic. But it was foreign to working class and the poor

all the same. They definitely enjoyed it, identified with it. But it was world

of sheer fantasy and escape. It was corruption of imagination. No wonder that

it coincided with discrediting the idea of collective action and strikes. It

spoke against big businessmen, but sought the easy way out of outwitting them

via mafia. This Robin Hood politics was certainly regressive although the

drapery it was cloaked in spoke of poor and systemic injustice.

class is central to the film is accepted by everyone including critics. So what

is it that requires our attention? That the ‘underdog’ story here doesn’t go

along the lines of ‘angry young man’ themes of Bollywood is as much recognition

of reality of 30 years of neo-liberal reforms and the shift in politics as well

as identity of ‘working class’ as we understand and not only a political choice

of playing to the gallery of aspiring middle class. If anything, it is

important to underline that even ‘angry young man’ was also a trope with which

cinema-going middle class of the 70s identified with and hence was as much an

effort to play to the gallery if not more. What is more, that image of ‘angry

young man’ (intricately linked to Amitabh Bacchan) had firm ground in upper

caste, middle- lower middle class imagination of seeing oneself as savior,

taking on the dirty world of mafia, corruption, politicians, worshipping

‘mother’ while displaying a nihilistic ethic otherwise. There was a cathartic

pleasure involved in seeing ‘angry young man’ do the dirty job for you on

screen while speaking language of authority and power. This language was

captivating. It was poetic. But it was foreign to working class and the poor

all the same. They definitely enjoyed it, identified with it. But it was world

of sheer fantasy and escape. It was corruption of imagination. No wonder that

it coincided with discrediting the idea of collective action and strikes. It

spoke against big businessmen, but sought the easy way out of outwitting them

via mafia. This Robin Hood politics was certainly regressive although the

drapery it was cloaked in spoke of poor and systemic injustice.

There

have been plenty of films in last 30 years which have not gone the route of

‘angry young man’ and yet either ended up glamorizing mafia or acquiring riches

one way or the other. ‘Gully Boy’ resolutely stays away from either. It is

striking to locate Murad and poverty and working class experience that shapes

him. The sheer in-your-face inequality he encounters, struggles against system,

abusive father, ghettos all are familiar experiences of millions of people. and

it is equally essential to note that merely because these are all familiar, out

in the open experiences has not led people to take up arms or rise in

rebellion. The overarching thread that knits this unjust and unequal ‘system’

together is something that Murad is grappling with. Murad has seen both options

on offer from the ‘system’: abyss of everyday life to make a living, or to make

an acceptable dent in hierarchy through art to climb the social ladder. He is

not joining mafia, or political party- which is curiously considered to exist

somehow more ‘outside the system’ by some.

He is angry, but he is not naïve. He vents his anger through poetry but

he understands the reality of something called ‘socially necessary labor time’

which capitalism neatly develops and determines the worth of each and every

commodity including art. He is aware that capitalism has robbed him and

millions like others to properly even ‘dream’. But at the same time, there is a

possibility for someone in Murad’s position that capitalism opens up to reach

out to millions of people which hitherto was impossible. Social media or

otherwise, it is only under capitalism that music and other cultural forms

develop and travel far and wide extending their influence in unimaginable

forms. This exposure to information, culture, and media leads to

democratization. It leads to and shapes up eco-systems which thrive upon

cosmopolitan experience. Marx was enthusiastic about city life for this very

reason. The city was to be praised for at least one thing, the escape it offers

from what he called “the idiocy of village life“. The ghettos

working people in cities inhabit often resemble the villages and customs, caste

and creed divisions. But the possibility of cosmopolitan experience and the

process of individuation that capitalism offers is what Murad’s search is for. Murad

is clear about focus of his struggle: roti, kapada, makan aur internet. Murad’s

journey of rapping and hip hop is hence less about aspiring luxuries and riches

and more about his struggle against the tyranny of everyday life of de-skilling

and creative numbness that is enforced on millions of working people as

capitalism warrants to have an army of cheap labor that is easily replaceable;

men and women who have retrospectively taken spots of robots yet to arrive. In

short, would Murad rap if there was no contest? Yes. He would. Would he

continue to rap if he lost? Yes, he would. That is the puzzle many people seem

to be completely missing.

have been plenty of films in last 30 years which have not gone the route of

‘angry young man’ and yet either ended up glamorizing mafia or acquiring riches

one way or the other. ‘Gully Boy’ resolutely stays away from either. It is

striking to locate Murad and poverty and working class experience that shapes

him. The sheer in-your-face inequality he encounters, struggles against system,

abusive father, ghettos all are familiar experiences of millions of people. and

it is equally essential to note that merely because these are all familiar, out

in the open experiences has not led people to take up arms or rise in

rebellion. The overarching thread that knits this unjust and unequal ‘system’

together is something that Murad is grappling with. Murad has seen both options

on offer from the ‘system’: abyss of everyday life to make a living, or to make

an acceptable dent in hierarchy through art to climb the social ladder. He is

not joining mafia, or political party- which is curiously considered to exist

somehow more ‘outside the system’ by some.

He is angry, but he is not naïve. He vents his anger through poetry but

he understands the reality of something called ‘socially necessary labor time’

which capitalism neatly develops and determines the worth of each and every

commodity including art. He is aware that capitalism has robbed him and

millions like others to properly even ‘dream’. But at the same time, there is a

possibility for someone in Murad’s position that capitalism opens up to reach

out to millions of people which hitherto was impossible. Social media or

otherwise, it is only under capitalism that music and other cultural forms

develop and travel far and wide extending their influence in unimaginable

forms. This exposure to information, culture, and media leads to

democratization. It leads to and shapes up eco-systems which thrive upon

cosmopolitan experience. Marx was enthusiastic about city life for this very

reason. The city was to be praised for at least one thing, the escape it offers

from what he called “the idiocy of village life“. The ghettos

working people in cities inhabit often resemble the villages and customs, caste

and creed divisions. But the possibility of cosmopolitan experience and the

process of individuation that capitalism offers is what Murad’s search is for. Murad

is clear about focus of his struggle: roti, kapada, makan aur internet. Murad’s

journey of rapping and hip hop is hence less about aspiring luxuries and riches

and more about his struggle against the tyranny of everyday life of de-skilling

and creative numbness that is enforced on millions of working people as

capitalism warrants to have an army of cheap labor that is easily replaceable;

men and women who have retrospectively taken spots of robots yet to arrive. In

short, would Murad rap if there was no contest? Yes. He would. Would he

continue to rap if he lost? Yes, he would. That is the puzzle many people seem

to be completely missing.

Now

let us turn to the question of identity. The objection that Murad is Muslim and

believer is not central focus of the film has upset many critics, especially

since hip hop and its association with Black resistance, and Black Panthers He

is not joining mafia, or political party- which is considered to exist somehow

more ‘outside the system’ by some. I would argue here is the case of critics

simply projecting their preferences onto rappers/ artists to carry out certain

political movements and tackle questions. Mumbai witnessed the riots in

1992-93. Sri Krishna Commission report has not been implemented even till date.

No political party has taken up the cause of riot victims and Muslims thrown in

ghettos in reality. Is it the case that ‘Gully Boy’ should have done a fantasy

trip where Murad becomes a star rapper who waxes eloquent about Muslim pride

and self-respect and demand abolition of ghettos et al? MIM and Asaduddin

Owaisi have steered their politics in this direction, but it doesn’t resonate

with larger oppressed minorities the way Black protests did in US. The

correspondence between art and politics is such that politics inspires art or

at least elevates and supports it and not the other way round. Dalit Panthers

led by Namdev Dhasal and their protest poetry in Marathi certainly is great

example of convergence of art and politics. But Dalit protests and politics

could grow and reach out to other oppressed sections because of its ‘part of no

part’ social identity which resembled proletariat. We have several examples of radical

Dalit balladeers, singers (Anna Bhau Sathe, Sambhaji Bhagat, Kabir Kala Manch,

Waman Kardak, Ginni Mahi to name a few). Unless something similar happens in

Muslim social and political experience, it is cynical to expect films like

‘Gully Boy’ to start a fire when there is none. The film is shrewd enough to

convey how ghetto has shaped up even the employment choices for Murad: AC

repairing, driving, mechanic, car stealing, drugs, and music. (The double

exclusion of Muslim women via patriarchy and ghettoisation is depicted even

more sensitively- in Safeena’s fight for continuing her education and

relationship with Murad as well as Murad’s mother having to struggle with her

husband and then brother refusing to support her) On an aside, Do Naezy and

Divine and other rappers in India, (many of whom are from minority communities

and who have inspired this film) situate themselves in ‘Muslim/ Christian

Pride’ frames? They do not. They speak of ghettos but also they speak of so

many other issues and situations. And their rap is about local pride,

brotherhood, everyday struggle as well.

let us turn to the question of identity. The objection that Murad is Muslim and

believer is not central focus of the film has upset many critics, especially

since hip hop and its association with Black resistance, and Black Panthers He

is not joining mafia, or political party- which is considered to exist somehow

more ‘outside the system’ by some. I would argue here is the case of critics

simply projecting their preferences onto rappers/ artists to carry out certain

political movements and tackle questions. Mumbai witnessed the riots in

1992-93. Sri Krishna Commission report has not been implemented even till date.

No political party has taken up the cause of riot victims and Muslims thrown in

ghettos in reality. Is it the case that ‘Gully Boy’ should have done a fantasy

trip where Murad becomes a star rapper who waxes eloquent about Muslim pride

and self-respect and demand abolition of ghettos et al? MIM and Asaduddin

Owaisi have steered their politics in this direction, but it doesn’t resonate

with larger oppressed minorities the way Black protests did in US. The

correspondence between art and politics is such that politics inspires art or

at least elevates and supports it and not the other way round. Dalit Panthers

led by Namdev Dhasal and their protest poetry in Marathi certainly is great

example of convergence of art and politics. But Dalit protests and politics

could grow and reach out to other oppressed sections because of its ‘part of no

part’ social identity which resembled proletariat. We have several examples of radical

Dalit balladeers, singers (Anna Bhau Sathe, Sambhaji Bhagat, Kabir Kala Manch,

Waman Kardak, Ginni Mahi to name a few). Unless something similar happens in

Muslim social and political experience, it is cynical to expect films like

‘Gully Boy’ to start a fire when there is none. The film is shrewd enough to

convey how ghetto has shaped up even the employment choices for Murad: AC

repairing, driving, mechanic, car stealing, drugs, and music. (The double

exclusion of Muslim women via patriarchy and ghettoisation is depicted even

more sensitively- in Safeena’s fight for continuing her education and

relationship with Murad as well as Murad’s mother having to struggle with her

husband and then brother refusing to support her) On an aside, Do Naezy and

Divine and other rappers in India, (many of whom are from minority communities

and who have inspired this film) situate themselves in ‘Muslim/ Christian

Pride’ frames? They do not. They speak of ghettos but also they speak of so

many other issues and situations. And their rap is about local pride,

brotherhood, everyday struggle as well.

Associated

with this is the question of what constitutes rap? What constitutes art and

what is its politics? Is rap mere noise and clever play of words with drum

beats? Or is it song of the oppressed? Perhaps evolution of hip hop (and before

that, art forms like Jazz) as protest music needs greater enquiry. It didn’t

start with motto of intervening in overt politics; hip hop started to challenge

the beats and tunes of disco in 1970s which sought to exclude the poor and

marginalized and catered to glossy, well-to-do patrons in sophisticated

dresses. Rap was born in streets and parks of New York suburbs like Bronx to

come up with an inviting tune which invited all to join the party/ fun. Over

the period, it integrated elements of soul, funk, techno, rock, disco; it also

took more explicit shape of protest music. Indian rap and hip hop may seem like

‘foreign’ and exotic influence at the outset. However, as Indian rappers have

time and again expressed, this ‘foreign’ sound is more authentic to their life

which captures the beat and the pace, the frenzy, excitement and fury of their

experience. This rap is protest against romantic/ cliched tunes of mainstream

Bollywood music which ‘dumbs down’ working people from experiments in their

art. The fact that Indian hip hop quickly evolved to speak the vernacular

languages and many artists from slums are coming up is promising. In

Althusserian terms, theirs is correct ‘working class instinct’; whether it

leads them to reach fully worked out ‘working class position’ and lead to

larger explicit political interventions is bit too premature. But, the very

fact that a mainstream commercial Hindi film provides this experiment a solid,

realist platform is heartening.

with this is the question of what constitutes rap? What constitutes art and

what is its politics? Is rap mere noise and clever play of words with drum

beats? Or is it song of the oppressed? Perhaps evolution of hip hop (and before

that, art forms like Jazz) as protest music needs greater enquiry. It didn’t

start with motto of intervening in overt politics; hip hop started to challenge

the beats and tunes of disco in 1970s which sought to exclude the poor and

marginalized and catered to glossy, well-to-do patrons in sophisticated

dresses. Rap was born in streets and parks of New York suburbs like Bronx to

come up with an inviting tune which invited all to join the party/ fun. Over

the period, it integrated elements of soul, funk, techno, rock, disco; it also

took more explicit shape of protest music. Indian rap and hip hop may seem like

‘foreign’ and exotic influence at the outset. However, as Indian rappers have

time and again expressed, this ‘foreign’ sound is more authentic to their life

which captures the beat and the pace, the frenzy, excitement and fury of their

experience. This rap is protest against romantic/ cliched tunes of mainstream

Bollywood music which ‘dumbs down’ working people from experiments in their

art. The fact that Indian hip hop quickly evolved to speak the vernacular

languages and many artists from slums are coming up is promising. In

Althusserian terms, theirs is correct ‘working class instinct’; whether it

leads them to reach fully worked out ‘working class position’ and lead to

larger explicit political interventions is bit too premature. But, the very

fact that a mainstream commercial Hindi film provides this experiment a solid,

realist platform is heartening.

The Author is an Independent Researcher based in New Delhi