Jesse Olsavsky

Jesse Olsavsky

Introduction

The advent of photography signals a new epoch in humans’ relationships to their pasts, asserts Roland Barthes in Camera Lucida, undoubtedly the most influential book written on the experience of photography. “Henceforth the past is as certain as the present, what we see on paper is as certain as what we touch.”[1] That which has been stands materially before us, not as myth, not as mystery, not as memory, but as real. The irony of these grand, largely unprovable metaphysical claims is that Barthes—burdened by the mortality the “that-has been” always suggests—seeks to read and feel beyond the historical past. He seeks to erase the past from the reading of the photograph. This essay will attempt to uncover and reconstruct the erased history of race within Camera Lucida (the book being used both as written text and archive of images). This history will not be History writ large, but merely a possible history, full of contingencies, wrong turns, silences, speculations, and alternatives.

The problem of race in Camera Lucida has already been much discussed. A lot of the debate focuses on some of the implicit, un-critiqued racial assumptions Barthes employs in his interpretation of photographs depicting people of African descent.[2] In short, the crux of the issue is, in one way or another, “How racist was Roland Barthes?” Shawn Michelle Smith effectively and productively answers this question but also importantly suggests a major implication: “Barthes obfuscates the presence of other historical subjects.”[3] Subjects dissolve in Camera Lucida, but so do histories. Hence, this essay, following cues from Smith, will move slightly beyond the existing debates on race in Camera Lucida to uncover some of what has been obfuscated. I will seek to show that Camera Lucida’s photographic archive, in a strange and obscure way, reveals an extensive historical narrative of blackness and of whiteness (particularly in the U.S. and France), from slavery, to emancipation, to imperialism, to the Civil Rights Movement.

Thus, this essay is less concerned with critiquing the undeniable racial logics at work in Camera Lucida, and more concerned with critiquing Barthes’ (and other postmodernists’) way of reading texts that erases, obfuscates, and trivializes the concrete histories that shape what we see and even how we see. Images and texts should not completely overpower us; nor should we consciously relinquish our critical capacities and let texts and images overpower us as an interpretive practice.[4] Discursive determinisms are methodologically just as dogmatic as economic determinisms (if not more so). My methodology for reading Barthes will focus on context as much as text, history as much as discourse. It will search out facets of the histories behind the people portrayed in Barthes’ archive (I will focus on the photographs of Jerome Bonaparte, Lewis Paine, De Brazza, William Casby, and A. Phillip Randolph). Abstract theory and imaginative speculations will stand alongside a hardy empiricism often absent in much cultural theory. After all, as Marx and Freud proved, obstinate empiricism and the highest flights of the theoretical fancy can and must go hand in hand.

Camera Lucida: The Studium, the Punctum, and the Silencing of History

Camera Lucida is an incredibly rich piece of work. It deftly employs many philosophic frameworks, from Freud to phenomenology, and is full of sharp aphoristic bursts on the nature of death, time, and existence. Yet the work is also Barthes’ attempt to flee existing frames, truisms, and tropes in order to uncover the “essence” of photography through his own experience. In short, Barthes “makes himself the measure of photographic meaning,” and develops his own terminology to decipher that meaning—studium and punctum.[5] History lurks at every corner of Barthes’ self-deciphering, yet I argue that Camera Lucida is marked by a persistent attempt to silence history, if not to transcend it.

Barthes formulates his notion of the studium through a confrontation with an unexpected revolution. Just as neoliberal imperialism began to tighten its grip, crushing democratic-socialist experiments across the world—most notably in Chile, where Pablo Neruda died of a broken heart—the Sandinista National Liberation Front seized power from the Somoza dictatorship (1979). History was happening before Barthes eyes, bringing history-making within photographs out into the open. For Barthes, this history-making, this history-happening, along with all the cultural and ideological assumptions we use to understand it, is the studium. Barthes employs images from the Sandinista Revolution to illustrate the presence of the studium as history-happening within the photograph. Yet history, contingency, action, and the commitments we employ in navigating all of this are not essence or meaning to Barthes. Theory must be detached from praxis; the meaning of photography must be ripped away from “the (photographic) banality of a rebellion in Nicaragua.”[6] Chatter to be silenced.

The punctum is Barthes means for personalizing and de-historicizing the past, for making it his own, and disconnecting it from present and future. “I am the very contrary of History, I am what belies it, destroys it for the sake of my own history.”[7] It’s personal and it’s political. The “that-which-has been” represents the field of death—the death of his mother—and the “that which will be” can only be his own impending death. No past, no future, only the present.

Such a marked contrast to the attitude of William Morris, the utopian artist and indelible optimist: “The past is not dead, it is living in us, and will be alive in the future which we are now helping to make.”[8] So, the punctum is that part of the image that “pricks” in the present, and is purportedly in excess of the past. In many cases, the punctum is a means to transcend time and space to understand photographed realities in terms of platonic ideas. Thus, the photo reveals to Barthes “slavery,” “death,” and the like in their essences. Interestingly, another indelible (perhaps naïve) optimist, Ernst Bloch, saw these aesthetic excesses as existing outside history. But for Bloch, these excesses—these punctums, so to speak—point towards history’s consummation: communism.[9] But no redemption, no Messiah, in art for Barthes; death must come.

It may, though, be impossible to distinguish the punctum from the studium. Just as hard to distinguish are the photograph and its referent. The referent, Barthes argues, persists through the photograph; the “that-which-has-been” presents itself most clearly in the photograph. History becomes present. For Barthes this “stubbornness of the referent” points towards the essence of photography, yet it is also an annoyance to be overcome, for most of the interpretive material provided by the referent within the photograph is defined by Barthes as mere studium, chatter and distraction that contains the essence but is not itself essence.[10] Herein resides the most notorious flaw of Camera Lucida. Many of the images chosen by Barthes illustrate the histories of race, slavery, imperialism, and civil rights, yet he obscures their histories and fails to question his own cultural assumptions in the quest for essence. As Smith best puts it: “Barthes explanation of the studium is laden with a paternal racism that readers are asked to ignore in pursuit of that which really interests him, the punctum. He calls upon the studium as if it is apparent and transparent, as if this lovely portrait [i.e. Van Der Zee portrait] could not be read in another way.”[11] There are other readings, other histories, contained within Barthes archive. What is concealed behind Barthes philosophical concerns and racial assumptions is a history of race ripe for the revealing.

Jerome Bonaparte: “Bourgeois” Revolutions, Slavery, and the White Gaze

Camera Lucida begins with a discussion of an 1852 photograph of Jerome Bonaparte (left)[12], the brother of Napoleon. Imperious, seeming experienced though unwise, ugly, and bourgeois to the bone, the Bonaparte in the photograph nevertheless amazed Barthes: “I am looking at the eyes that looked at the Emperor.”[13] Indeed, Jerome had looked upon the Emperor, served with him in his armies, and was King of Westphalia under his brother’s empire. Later, after the 1848 Revolutions, he served as President of the Senate under his nephew Emperor Napoleon III. He was an integral part to both the tragedy and the farce so viciously described by Marx.[14] Yet the tragedies and farces go much deeper, implicating modern bourgeois freedom with African slavery, and revealing an important act in the reinforcing of the Fanonian white gaze: the desire to look upon the Emperor.

Camera Lucida begins with a discussion of an 1852 photograph of Jerome Bonaparte (left)[12], the brother of Napoleon. Imperious, seeming experienced though unwise, ugly, and bourgeois to the bone, the Bonaparte in the photograph nevertheless amazed Barthes: “I am looking at the eyes that looked at the Emperor.”[13] Indeed, Jerome had looked upon the Emperor, served with him in his armies, and was King of Westphalia under his brother’s empire. Later, after the 1848 Revolutions, he served as President of the Senate under his nephew Emperor Napoleon III. He was an integral part to both the tragedy and the farce so viciously described by Marx.[14] Yet the tragedies and farces go much deeper, implicating modern bourgeois freedom with African slavery, and revealing an important act in the reinforcing of the Fanonian white gaze: the desire to look upon the Emperor.

The photograph of Jerome displays the social product of revolutions, or more precisely, of counterrevolutions (indeed, “the age of the photograph is also the age of revolutions,” writes Barthes).[15] Of modest bourgeois background, Jerome came of age just as his brother crushed Jacobinism for good. Jerome’s first aspiration was for empire and aristocracy—paintings of the time show him dressed as the King that Napoleon had crowned him. In 1848 came another burst of French Jacobinism, and yet again Jerome was catapulted by counterrevolution into a position of power. But this time he did not get his portrait painted; he was photographed. Now, instead of standing as an uncomfortable aristocrat, he stands as the proud bourgeois, top hat and all, who, with his class, had invoked universalistic ideals of freedom and equality to come into power, but turned on those ideas once in power. Freedom only ever meant freedom of trade.

These events have everything to do with slavery, colonialism, and the white gaze. To gaze in wonder at the Emperor—or even to gaze in awe “at the eyes that looked at the emperor”—is to constitute one’s political sight in terms of Empire, to see Empire as the whole, and to fragment all that is subject to it. This goes for Bonaparte as much as for Barthes. Jerome had briefly lived in America’s burgeoning “empire of liberty.” He married into a prominent Baltimore slaveholding family, and had a son and a nephew who later became noted southern slaveholders.[16] In France, the Bonaparte clan, as C.L.R. James bluntly put it, “hated black people.”[17] Napoleon restored slavery after the Jacobins and their slave allies had overthrown it. Jerome’s brother-in-law, Leclerc, led an army to disaster and death in Haiti, in his attempt to halt the Haitian Revolution. French slavery was abolished for good during the 1848 Revolution. During the Second Empire, though, the Bonapartes made sure that planters were well-indemnified for their lost “property,” protected planters’ economic interests, and kept the French Caribbean of Cesaire and Fanon in colonial subjection for years to come.[18] Empire, slavery, colonialism—all this served as the conditions for the possibility of Jerome Bonaparte’s bourgeois pompousness in his photograph.[19] Jerome gazed upon the Emperor; he saw Empire in its grandeur and black people in their servility. He helped forge the master-slave relationship that Fanon saw as the precondition for the white gaze.[20]

William Casby: Putting Masks on the Histories of Slavery and Freedom

Fanon never denied that Europeans had invoked ideals of freedom worth realizing; he only asserted that now it was up to others to realize those ideals.[21] In Europe and the Americas, the history of freedom became intertwined with the history of slavery, forcing hypocrisy and mendacity in ideals and practices. Masks had to be put on history, freedom had to be attached to a “democratic” capitalism, and both had to be detached from slavery. Slavery became the dead past, the “that-has-been,” not the foundations for the present, not even related to the present. Slavery became so detached from the present that Barthes needed a magazine photograph of a slave market to remind him “that such a thing existed.”[22] He never stopped to reflect that slave market and free market went hand in hand (and there are plenty of reminders of this). Masks are used to hide the history of slavery and freedom. These same masks may even hide or obscure the direly needed, other voices of freedom (remember Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth was banned for a long time in France).

An analogous process of masking goes on in Barthes interpretation of Richard Avedon’s photograph of William Casby, “born a slave.” Barthes argues that in order to communicate meaning, the photograph needs to take on a broader meaning-making abstraction. In the case of the Casby photograph, Barthes sees it solely as “the essence of slavery laid bare.”[23] As Smith best puts it, “In Barthes’ reading, the portrait of William Casby enters the realm of meaning as it comes to signify ‘slave,’ and ceases to register a singular face…a subject is transformed into an object.”[24] I do not differ with Smith’s reading of the photograph. However, I do believe that by putting the mask of “slavery” on Casby, Barthes not only objectifies him but also partakes in a wider cultural project of putting masks on the history of slavery. Casby becomes the object, the relic, of a dead past. He is only needed as a reminder of that past, and not as an embodiment of the links between past and present.

Yet William Casby does connect the past with the present, and is perhaps more in the present than in the past. His photograph was taken in 1963, one hundred years after the Emancipation Proclamation. His memories of slavery would have been few. He represents more than just slavery. His knowledge of emancipation, reconstruction, Jim Crow, and of Civil Rights would have been more direct and immediate. The photograph itself has more to do with the present (1963) than the past. Casby was photographed by Avedon while he was touring the South snapping pictures of civil rights activists. The Casby photo was published by Avedon and James Baldwin in a provocative political volume, Nothing Personal (1964), which catalogued contemporary freedom struggles, not past servitude.[25] Though it is impossible to know, Casby may have had much more to say about freedom than slavery.

Lewis Payne and the Civil Contract of Whiteness

In some respects, the photograph of Lewis Payne is the most important piece for Barthes reflections (well, second to the Winter Garden photograph). Rooted in the Payne photograph is a that-has-been which is death. “The punctum is: he is going to die.”[26] In that punctum, Barthes finds the essence of photography: the capturing of death, or that which is going to die. Barthes has not come up with a profound new reading of the Payne photograph; he is, in fact reading it as it was read in its time, as it was perhaps intended to be read. The strange, eerie irony here is that this reading is inextricably bound with the revamping of white supremacy in post-emancipation America.

Payne was the son of an Alabama slaveholder, and he worked briefly as a slave driver in Florida. He was a Confederate soldier, hanged in 1865 for complicity in the plot to assassinate Lincoln. Payne fought to keep slavery alive, even after the end of the war. The violent values of the slavocracy were bred into his bones, and even his own defense lawyer (a northerner) was appalled at the extent to which this was so: “These, then were the morals and instinct of the lad—it is right to kill Negroes, right to kill abolitionists….the torture of Negroes evidence of a commanding nature; concubinage with Negroes a delicate compliment to wives.”[27] Payne never recanted any of his convictions, and went to execution with solemnity, quietness, and grace.

The Payne photograph—as well as the hundreds of other widely circulated drawings, photographs, and engravings of Payne—had a major impact on the American public sphere. It indeed showed the ubiquity of death (“he is going to die”), but it also displayed the philosophic courage needed to face death (which Barthes himself was seeking). The South found a young and handsome hero out of which to weave myths about their lost cause and lost way of life. In the North, Payne was described as a “hero-villain,” a dignified martyr who just happened to be on the wrong side of things.[28] White folk on both sides could find something to admire in Payne—just as they did with Lee and Jackson—and the commonalities of courage and struggle in the face of death were used to mollify animosities between North and South. The successes of reconciliation became recompense for the failures of Reconstruction. And, as Dubois puts it: “All hatred that the whites once had for each other gradually concentrated itself on the Negro.”[29]

Certainly, photography speaks through the public sphere with various communities of viewers. It may even play a formative role in the creation of new forms of citizenship or identity. But to treat photography as somehow outside of the existing order of social and economic relationships, as Ariella Azoulay does, is politically deceptive. The Lewis Payne portrait shows how a photograph often circulates in the public sphere, and articulates with (and reinforces) existing forms of citizenship and domination based upon white supremacy.[30] The American “social contract” was premised upon white (male) supremacy. Its “civil contract of photography” reflected that reality. Only where substantial social movements materially and ideologically challenge the existing order of things can a new “civil contract of photography” (so to speak) begin to emerge.

Savorgnan De Brazza: Photographing “Benevolent” Imperialism

The photograph of de Brazza, sitting between two African boys dressed as sailors, is the most seemingly out of place photograph in Camera Lucida. It appears to serve no other purpose than to show that the punctum (the boy’s crossed arms) is often random, unexpected, and not “coded.” Codes, cultural norms, and histories belong to the studium, argues Barthes; thus, the hand rested on de Brazza’s thigh is not a punctum, but a studium “coded” by Barthes as “aberrant,” abnormal.[31] Yet there is much more to be “coded” in the relationship between de Brazza and the two black boys than the hint of homoeroticism. The relationship seems congenial, with some mutuality, and benevolence on the part of de Brazza, but nevertheless unequal. It is French imperialism revealing a little bit about itself in the process of justifying itself.

De Brazza was a famed French explorer, reformer, abolitionist, and imperialist. He represented European colonialism at its most benevolent (that is, at its least honest). He proved the pitfalls of European abolitionism by using antislavery ideology as the justification for colonization: colonization would eradicate slavery and other “uncivilized” practices in Africa. He conquered territory three times the size of France, more through trade and less through the rifle (the endpoint, though, notes Walter Rodney, was the same: dependency and underdevelopment for Africa, advanced capitalism for Europe).[32] In the 1880s de Brazza ruled the French Congo, and could boast that his regime was a bit less brutal and a bit more efficient than that of the nearby Belgian Congo. [33] In short, he ensured the exploitation of African labor and land through a policy of paternal benevolence.

The trouble of how to define the colonial situation and how to resist it was always a difficult one. Fanon broke painfully with Cesaire over the issue of Martinician independence. Cesaire the politician (not the poet) saw the material benefits of staying bound to France. Fanon saw the master-slave, colonizer-colonized, relationship as inherently a fight to the death; only full independence would shatter the political and psychological inferiority complexes.[34] But what does the photograph of de Brazza tell us about imperialism? It does show that colonialism functioned through complex divisions, interrelationships, antagonisms, paternalism, and bare domination, which were harder to critique, harder to overthrow, than usually realized. It also shows how easy it is to photograph violent relationships without the violence.[35] “But isn’t every square inch of our cities a crime scene? Every passer-by a culprit? Isn’t it the task of the photographer—descendant of the augurs and haruspices—to reveal guilt and to point out the guilty in his pictures?”[36]

Phillip Randolph: Confusing Air and Body, Obscuring Racial Conflict

As yet, “there’s no art to find the mind’s construction in the face,” Shakespeare wrote.[37] One thing that photography suggests—particularly in Avedon’s work—is that essence may be in the face and not necessarily behind it. Barthes uses a 1976 portrait of A. Phillip Randolph by Avedon to develop this line of thought. Photographs, of course, can render the that-has-been of the body. Yet, without piercing into the body, without getting at the mysterious soul, photography can, says Barthes, reveal the essence of a person. For Barthes, this is the “air” of the photograph, that intractable, undefinable substance that follows the body like a shadow, and defines the person. In the aging A. Philip Randolph, Barthes reads an “air” of benevolent, completely harmless “goodness.” In addition, Barthes senses in the “air” “no impulse of power: that is certain.”[38] This is Barthes reading death into life, confusing ailment with air, and in the process severely distorting the “impulse of power” that Randolph infused into the people and society around him.

Barthes defines Randolph by abstract “air” (“no impulse of power”), but also by concrete politics (“the leader of the American Labor Party”).[39] The two descriptions reinforce each other, showing how use of the abstraction “air” informs an interpretation of the past, in fact obscuring the past. Politically and historically to Barthes, Randolph is simply “leader of the American Labor Party.” Indeed, Randolph was involved with this group, yet it was one of the less important and less defining aspects in Randolph’s career as agitator for Civil Rights and Socialism. The American Labor Party was a short-lived, democratic-socialist party started during the Depression. Small and full of the usual leftist sectarian factionalism, the organization disintegrated in the 1950s. As far as I can find out, Randolph never led the organization.[40] The title of “leader” of a defunct organization certainly reflects Barthes characterization of Randolph as worn out, without any “impulse of power,” and full of naïve and benevolent goodness that never harmed anyone, nor changed the world. But this ignores the impact of Randolph as a black union organizer and as Civil Rights leader. It shows Barthes ignorance of race’s role in American politics (as well as his tremendous ignorance of race in French politics, from the Haitian Revolution to the Algerian Revolution). Aesthetically and interpretatively, Barthes confuses old age and ailment of the body as lack of essential power.[41]

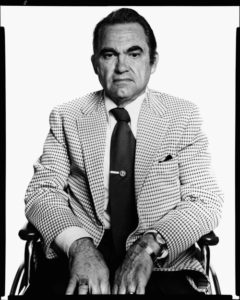

Naturally, I would like to believe that there is an impulse of power lingering in the Randolph portrait that can still have affect and effect today. As Wordsworth wrote of Toussaint L’Ouverture after his death: “Thou hast left behind/ Powers that will work for thee; air earth, and skies;/ There’s not a breathing of the common wind/That will forget thee.”[42] I myself suffer from this same romantic naivety and optimism. Yet there may be something politically necessary in finding power in the past, the that-has-been, the that-has-died. Remember, Avedon’s portrait of Randolph was made for a 1976 collection “The Family.” It consists of portraits of powerful American figures—from Cesar Chavez, to Reagan, to Kissinger—suggesting 200 years of national-class-racial (yet somehow familial) conflict and power struggle in America. One of the photographs in this 1976 collection is of George Wallace (left).[43] Though physically debilitated from a failed assassination attempt, one could not and should not construe the image as displaying “no impulse of power” or merely that which is going to die. The past lives on and stubbornly survives, as Wallace did. Hopefully the actual “air” and legacy of A. Phillip Randolph can be used to navigate both the past and the present. The uprightness, righteousness, humility displayed in the Randolph portrait should be used to combat the still-surviving contempt and indignation evinced in the Wallace portrait.

Naturally, I would like to believe that there is an impulse of power lingering in the Randolph portrait that can still have affect and effect today. As Wordsworth wrote of Toussaint L’Ouverture after his death: “Thou hast left behind/ Powers that will work for thee; air earth, and skies;/ There’s not a breathing of the common wind/That will forget thee.”[42] I myself suffer from this same romantic naivety and optimism. Yet there may be something politically necessary in finding power in the past, the that-has-been, the that-has-died. Remember, Avedon’s portrait of Randolph was made for a 1976 collection “The Family.” It consists of portraits of powerful American figures—from Cesar Chavez, to Reagan, to Kissinger—suggesting 200 years of national-class-racial (yet somehow familial) conflict and power struggle in America. One of the photographs in this 1976 collection is of George Wallace (left).[43] Though physically debilitated from a failed assassination attempt, one could not and should not construe the image as displaying “no impulse of power” or merely that which is going to die. The past lives on and stubbornly survives, as Wallace did. Hopefully the actual “air” and legacy of A. Phillip Randolph can be used to navigate both the past and the present. The uprightness, righteousness, humility displayed in the Randolph portrait should be used to combat the still-surviving contempt and indignation evinced in the Wallace portrait.

Conclusion

I have attempted to show that the methods of interpretation used by Barthes consistently conceal the workings of history (that is how the that-has-been came to be), thus ignoring some of the cultural and political implications of his archive, and trivializing a whole field of interpretative possibilities that place photography squarely within the history of modernity (though to be fair, Barthes was never interested in any of this stuff to begin with). Moreover, I have shown that, when deciphered historically, Barthes archive narrates an entire history of race (both whiteness and blackness)—or, at least, key moments in this history—from slavery all the way to the Civil Rights Movement. That history is indeed one of struggle, resistance, aspiration, and possibilities. But more importantly Barthes’ archive shows the importance of slavery, race, imperialism, and struggles against them to the constitution of capitalist modernity. That the hidden history of race in Camera Lucida is so profound and complete perhaps may say something about the ways the development of photography is bound to both the formation of race and capitalism.

The author is Assistant Professor, Duke Kunshan University, China and a specialist in the history of African American activism against slavery and the struggle for black emancipation in nineteenth century USA.

References:

[1] Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, Translated by Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 2010), 88.

[2] See, for example, Shawn Michelle Smith, “Race and Reproduction in Camera Lucida,” in At the Edge of Sight: Photography and the Unseen (Duke University Press, 2013), 23-38; Carol Mavor, “Black and Blue: The Shadow’s of Camera Lucida,” in Geoffrey Batchen, ed., Photography Degree Zero: Reflections on Roland Barthes Camera Lucida (MIT Press, 2009), 211-235.

[3] Smith, 27.

[4] Laura Marks, “Introduction,” Touch Sensuous Theory and Multisensory Media. The irony here is that in attempting to escape “euro-centric” forms of seeing, Marks reinforces them. To let the image overpower you—that is, to let human technological creations overpower you—does not allow one to escape “euro-centric” forms of instrumental rationality. Instead, instrumental reason—and the discourses of domination that often go with it—are simply replaced with an instrumental irrationality which neither circumvents nor critiques the discourses or realities of domination.

[5] Smith, 23.

[6] Barthes, 23.

[7] Barthes, 65.

[8] E.P. Thompson, William Morris: Romantic to Revolutionary (Oakland, California: PM Press, 2011), 590.

[9] Ernst Bloch, “The Conscious and known Activity within Not-Yet-Conscious, the Utopian Function,” in The Utopian Function of Art and Literature (MIT Press, 1988), 103-141.

[10] Barthes, 6.

[11] Smith, 24.

[12] Bonaparte photo retrieved from http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jerome_bonaparte.jpg December 10, 2015.

[13] Barthes, 3.

[14] Karl Marx, “The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon,” in Saul Padover, ed., Karl Marx on Revolution (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1971), 243-329.

[15] Barthes, 93.

[16] F.A. Richardson and W.A. Bennett, Baltimore: Past and Present, With Biographical Sketches of Its Representative Men (Baltimore: Richardson & Bennett, 1871), 401-404.

[17] C.L.R. James, The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution (New York: Vintage Books, 1963), 267.

[18] Robin Blackburn, The Overthrow of Colonial Slavery: 1776-1848 (London: Verso, 1988), 502-505.

[19] It also may suggest a relationship between Barthes desire to look upon the Emperor and his condescending attitudes towards people of African descent.

[20] Frantz Fanon, Black Skin White Masks, Translated by Richard Philcox (New York: Grove Press, 2008).

[21] Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, Translated by Constance Farrington (New York: Grove Press), 311-316.

[22] Barthes, 80.

[23] Barthes, 34.

[24] Smith, 28.

[25] For Historical Background to Casby photograph, see Deborah Willis and Barbara Krauthammer, Envisioning Emancipation: Black Americans and the End of Slavery (Temple University Press, 2013), 144-145. My reading of the Casby photo is largely indebted to this work.

[26] Barthes, 96.

[27] Betty J. Ownsbey, Alias “Paine”: Lewis Thornton Powell the Mystery Man of the Lincoln Conspiracy (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarlane,1993), 183.

[28] Ownsbey, 118-126.

[29] Dubois, Black Reconstruction, 1860-1880 (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992), 125.

[30] Ariella Azoulay, The Civil Contract of Photography (New York: Zone Books, 20080.

[31] Barthes, 51.

[32] Walter Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa (Howard University Press, 1981), 140.

[33] Edward Berenson, Heroes of Africa: Five Charismatic Men and the Conquest of Africa (University of California Press, 2011), 49-83. People actually still write books like this.

[34] Fanon, Black Skin White Masks, 64-89; The Wretched of the Earth, 35-95.

[35] And maybe it also shows how hard it is to actually capture violence for political purposes without banalizing or trivializing it.

[36] Walter Benjamin, “Little History of Photography,” in Jennings, Eiland and Smith eds., Walter Benjamin: selected Writings Volume 2 (Harvard University Press, 1999), 527.

[37] Macbeth 1.4, 14-15.

[38] Barthes, 110.

[39] Barthes, 110.

[40] On Randolph’s connection to socialist movements in the U.S., see Jervis Anderson, A Philip Randolph: A. Biographical Portrait (University of California Press, 1986), 104-108, 120-21, 147-149; Andrew Kersten, A. Philip Randolph: A Life in the Vanguard (New York Rowman and Littlefield), 124-127.

[41] On Randolph’s physical ailments in old age, see Anderson, 350-351. .

[42] William Wordworth, “To Toussaint L’Ouverture” in William Wordsworth: The Major Works (Oxford University Press, 2008), 282.

[43] Wallace phot retrieved from http://www.avedonfoundation.org/ December 12 2014.