Saqib Khan

Introduction

Introduction

In the run-up to the 2020 Bihar Assembly election, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has been trying to portray itself as an equal partner in its alliance with the Janata Dal (United) (JD) (U) and a key player in the state’s electoral politics. From 11.6 per cent vote share in the 1990 Assembly election, BJP gradually consolidated its position in the state in the 1990s and 2000s and became a significant force in Bihar’s electoral politics by 2010. The 2010 election marked its biggest electoral victory in terms of number of seats, and it formed the alliance government in that year. While its ally JD (U) won 115 seats in 2010, BJP won 91 seats which was its highest ever tally in Bihar. Though the Mahagathbandhan (Grand Alliance) gave it a crushing defeat in 2015, the party was still able to garner 24.4 per cent vote share.

So, what explains the growth of BJP in Bihar? This article analyses the party’s electoral performance in the Assembly elections from 1990 to 2015 and in the Lok Sabha elections from 1991 to 2019 in terms of seats won and votes polled. It argues that caste and community configurations and the alliance with JD (U) were crucial for the growth of BJP in Bihar.

BJP’s National Rise

The emergence of the BJP as India’s strongest political party in the 1990s changed the face of Indian politics (Hansen and Jaffrelot 1998). At the national level, the BJP saw meteoric rise and geographical expansion from 1989 to 2004 (Sridharan 2005). This was especially true in terms of the number of seats won by the party in the Lok Sabha elections. From mere 2 Lok Sabha seats in 1984, the party won 85 seats in 1989 and received 11.36 per cent of the vote share. Its vote share jumped to 20.11 per cent in 1991, taking it to 120 seats and the second largest party; in 1996 with the almost similar vote share it jumped to 161 seats and it emerged as the single largest party. In 1998, it came to power with 25.59 per cent of the vote and 182 seats; in 1999 it got 23.75 per cent of vote and 182 seats again. The party remained in the power at the Centre till 2004 and was unseated by the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) in that year. It came back strongly in 2014 with 282 seats and 31 per cent vote share and bettered its performance in the 2019 election by winning 303 seats and 37.4 per cent vote share.

Configurations of caste and community, and coalition or alliances have played one of most important roles in this national electoral rise and expansion of the BJP. Looking into the forces behind the BJP’s emergence as a national party, Heath (1999) saw the “acquisition of new territory and new allies” as the factors that transformed it into one of the main political forces in India (p. 2511). Heath outlined a three-tiered growth of BJP in its appeal. First was the continuation of the support of upper castes in states where the Jan Sangh became a significant political force in the 1950s and 1960s; second was the new social base comprising Other Backward Classes (OBCs) in states in the 1970s and 1980s; third was the rapid gain among Scheduled Castes (SCs) and the emergence of the party as a significant political force in states post-1989. According to Heath, allies have played a crucial role in this rise of the BJP, especially among the SCs and Muslims. The crucial role of allies is also highlighted by Sridharan (2005), who saw coalition-building as an important strategy for the expansion of BJP across Indian states between 1989 and 2004. According to Jaffrelot (2005), the BJP has made substantial gains in those states where it had made alliances with regional parties.

Chibber (1997) saw the electoral success of BJP at the national level in the early 1990s in terms of the party’s “ability to forge a coalition between religious groups (especially Hindus) and the economic interests of the middle classes”, which is, dissatisfaction of middle classes with state intervention in the economy (p. 639). According to Chibber, policies of the developmental state- secularism and economic intervention- provided the political opportunity structure for BJP to build this coalition between the above two groups.

More recently, in his analysis of 2014 Lok Sabha, Sridharan (2014) sees pro-BJP sentiment rising as we go up the class hierarchy, as well as the caste hierarchy, and this indicates support for the emergence of a loose, not compact, “new social bloc” of class and caste privilege (p. 75). Similarly, Jaffrelot (2015) sees a combination of class-based voting patterns (middle class, neo-middle class, socio-economically differentiated OBCs) as well as caste and community configurations as leading to the success of BJP at the national level.

BJP’s electoral performance in Bihar

Assembly Elections (1990-2015)

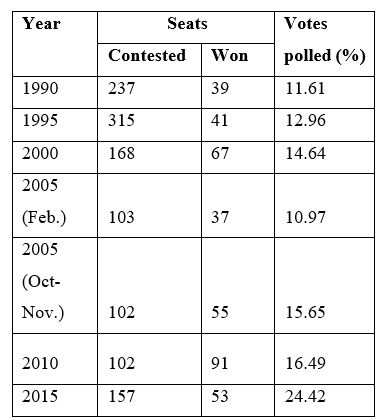

Table 1 shows the number of seats contested and won as well as vote share polled by BJP since the 1990 Assembly election in Bihar. When contesting the elections alone, the party contested more seats than as a part of the NDA. It can be seen that since the 1990s the party has gradually increased its tally of seats with every election (except February 2005 election). While in the 1990s it could win less than 50 seats, its tally in 2000 election jumped to 67. Its vote share also increased to more than 14 per cent. The BJP, however, suffered a setback in the first election of 2005 where its tally of seats fell down to 37 and its vote-share remained around 11 per cent. It recovered in the second election held in October-November in the same year. Though its tally of 55 seats was less than that of the 2000 election, its vote share jumped to more than 15 per cent. The 2010 election was the high-point for the party. Its tally of 91 seats and more than 16 per cent of vote share were its biggest electoral achievements since 1990 in the state. Even though it suffered a reverse in the 2015 election by winning only 53 seats, its vote share further increased to more than 24 per cent. Thus, from 39 Assembly seats and 11.61 per cent vote share in 1990, BJP consolidated its electoral position by winning 91 seats in the 2010 election and keeping its vote share to more than 24 per cent in the 2015 election.

Table 1

Seats and vote share for BJP in Bihar Assembly elections: 1990-2015

Lok Sabha Elections (1991-2019)

Source: Election Commission of India

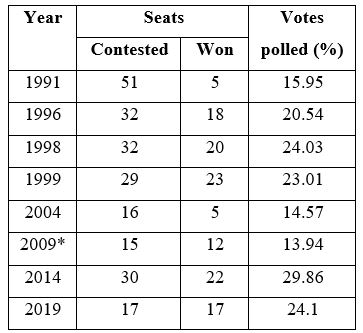

Table 2 shows the number of seats contested, won and per cent of votes polled by BJP in Bihar in the Lok Sabha elections from 1991 to 2019. From 5 seats in 1991, it reached a high of 23 seats in 1999. However, it only won 5 seats in 2004. Though suffering reverses in the 2004 and 2009 elections, the party defied the national trend in 2009 election by winning 12 of the 15 seats it contested in the state. In both 2014 and 2019, BJP’s performance in Bihar reflected the national outcome. In 2014, it reached a high of 22 seats with almost 30 per cent vote share- its highest in Lok Sabha elections in the state. Though its vote share came down to 24 per cent in 2019, the party won all the 17 seats it contested.

Table 2

Seats and vote share for BJP in Bihar in Lok Sabha Elections: 1991-2019

Source: Election Commission of India

*Data taken from National Election Study 2009, Economic and Political Weekly

BJP’s growth in Bihar

The factors for the rise of BJP at the national level in the 1990s, namely the configurations of caste and community and coalitions or alliances have played an important role in the party’s rise in Bihar as well. There was a close link between this configuration and alliance of BJP first with Samata Party and then with JD (U).

Caste and community configurations

Within the configurations of caste and community, the growth of BJP in Bihar was linked to the simultaneous process of the rise of backward castes and the shift of upper castes from Congress towards the BJP. The beginning of the 1990s saw the rise of backward castes in electoral politics in Bihar (Kumar 2002, 2004; Robin 2009). The real shift in the political sphere and the assertion of backward caste politics in Bihar could be seen from 1995 Assembly elections (Kumar 1999, 2002). This was evident from a changed political representation that saw a decline of upper caste-dominated Congress and the rise of backward castes, particularly Yadavs under Janata Dal and Kurmis and Koeris under Samata Party.[1] This changed political reality had two important implications for the rise of BJP in Bihar. Firstly, the decline of Congress in Bihar meant that there was a shift of upper caste votes towards BJP (Kumar 2002, 2004; Ananth 2005). Secondly, it was the coming together of the BJP-Samata Party alliance in 1995. It ensured that Koeris and Kurmis gradually came to support the alliance. This alliance also paved the way for the JD (U) and BJP alliance in 1999.

This coming together of backward castes like Koeris and Kurmis and upper castes was the result of split among the backward castes. Supporters of Janata Dal once upon a time, the absolute dominance of Janata Dal by Yadavs led these two castes to reconsider their political options in Bihar.[2] These castes, thus, aligned with the upper castes to fight the Yadav domination (Yadav 2004). According to Ananth (2005), there was some sort of ‘consensus among the upper castes to rope in sections of the OBCs and even concede the political leadership to an OBC leader against the dominance of Yadavs led by Lalu Prasad Yadav’ (p. 5143).

Kumar (1999) sees the increasing presence of the BJP in Bihar due to its growing popularity among the upper caste voters. Traditionally Congress supporters, the upper castes moved towards the BJP and its alliance partner, the Samata in a big way during the 1996 and 1998 Lok Sabha elections. Kumar shows that BJP which got only 28.7 per cent of the upper caste votes in 1995 Assembly elections, got 59.5 per cent of their vote in 1996 Lok Sabha elections and 77.6 per cent of their vote in 1998 Lok Sabha election (p. 2477). The fear of implementation of land reforms, as suggested by Bandhopadhyay Committee report in 2008, also played an important role in consolidation of upper castes towards BJP, especially before the 2010 Assembly elections (Jha 2010).[3]

It has been argued that apart from the upper castes, the BJP also tried to woo other castes and communities. The 1990s saw a growing support for BJP among the OBCs (Kumar 1999). It has tried to woo sections of the OBCs and EBCs particularly from 2000 Assembly elections onwards (Robin 2009). The party has particularly targeted the Yadavs from among the OBCs. This could be seen from the fact that after the 2000 Assembly elections, Yadav MLAs accounted for all 10.4 per cent of all BJP MLAs, and formed the second largest group after the Rajputs (Robin 2004). Before the formation of Jharkhand, BJP had also gained among non-upper castes in Chhotanagpur tribal belt (Hauser 1997). Though the upper castes still give the greatest support to the BJP, followed by the OBCs, the Scheduled Tribes (STs), the SCs and the Muslims, respectively, Heath (1999) shows that over the years in the 1990s, there has been a shift from the over reliance of the upper castes to representation from OBCs and SCs.

Nevertheless upper castes have traditionally stood behind BJP in Bihar. This is true even for the 2020 election. Nearly half of the BJP’s 46 candidates for the second phase of voting belong to the upper castes. Thus, the party’s electoral strategy has been to keep its upper caste support base intact while making inroads in the sizeable OBC and Dalit votes.

Over the years, there have also been attempts by the BJP to see itself as above caste and community configurations in Bihar. For example, the 2010 victory of NDA in Bihar was portrayed by BJP national leadership and sections of media as the ‘victory of development over identity politics’ and to show that it was only parties like the RJD that indulged in such politics. Despite such attempts, caste and community configurations continue to play a crucial role even for parties like the BJP in successive elections in the state. In fact, in the run up to the 2015 Assembly election, it was claimed by a senior BJP leader that the election was “80 per cent caste and 20 per cent Modi factor” (Chowdhury 2015).

The Alliance Factor

In this caste and community configuration, BJP’s alliance with Samata Party and later JD (U) was extremely important. Alliances with regional parties like Samata Party in Bihar had played an important role in giving a ‘breakthrough’ to BJP in 1996 in terms of seats (Prasad 1997; Hansen and Jaffrelot 1998). Hansen and Jaffrelot (1998) saw two reasons for this alliance between the old socialists of Samata Party and the BJP. The first was BJP’s history of being an active ally of all non-Congress alliances in Bihar, and the second was a shared concern for the defence of owner cultivators (p. 14).

This ‘upper- backward caste’ alliance was crucial for the rise of BJP in Bihar since the 1996 Lok Sabha elections (Hauser 1997). It challenged to an extent Lalu Yadav’s “Muslim-Yadav” alliance. There was also an increase in the number of Lok Sabha seats for the BJP which rose from 120 in 1991 to 161 in 1996; in this Bihar contributed 18 MPs (Prasad 1997). The BJP also emerged as the most dominant party in south Bihar, winning 12 of the total 14 seats from this region both in 1996 and 1998 Lok Sabha elections (Kumar 1999).

This alliance of BJP with Samata/JD (U) has some important political consequences for the BJP in Bihar. Firstly, the alliance has ensured that while BJP retains the support of four upper castes- Brahmin, Bhumihar, Rajput and Kayastha, the JD (U) retains its support among OBCs, particularly the two non-Yadav dominant OBC groups: Kurmis and Koeris, Extremely Backward Classes (EBCs) and sections of Muslims. Secondly, the alliance has enabled BJP to reach out to other caste groups besides the upper castes, especially from among the OBCs. For example, in 1996 its alliance with the Samata Party enabled it to make inroads among Kurmis and Koeris (Hansen and Jaffrelot 1998: 14). This was also reflected in its attempts to woo Yadavs from among the OBCs and also the EBCs, especially from 2000 Assembly elections onwards.10 The support for BJP by the EBCs can also be linked to the assertion of backward castes in the 1990s in Bihar whereby backward castes like Yadavs, Kurmis and Koeris rose into political spotlight, while the EBCs languished as electoral fodder for the upper backwards (Mishra 2010).

Thirdly, as seen in the 2010 Assembly elections, while BJP managed to consolidate its hold among upper castes, it also benefited from the rainbow social coalition crafted by Nitish Kumar (Shah 2010). This was particularly true in the case of Muslims where BJP was able to make inroads in both 2009 Lok Sabha and 2010 Assembly elections.

BJP’s swinging alliance in Bihar

BJP’s alliance with JD (U) has not been completely smooth. The seventeen-year old alliance fell apart in 2013 when Nitish Kumar-led JD (U) broke away with the BJP over its decision to name Narendra Modi the party’s prime ministerial candidate for the 2014 Lok Sabha election. In that election, the BJP won 22 out of the 30 seats it contested with a vote share of almost 30 per cent. In the 2015 Assembly election, JD (U) was part of the Mahagathbandhan (Grand Alliance) together with RJD and Congress and it trounced the BJP-led alliance consisting of other parties like the Lok Janshakti Party (LJP), Rashtriya Lok Samata Party (RLSP) and the Hindustani Awam Morcha (Secular) (HAM-S). However, the BJP was able to secure 24.4 per cent of vote share- the highest among all parties. The mandate of 2015 election got a new twist and the alliances saw a reconfiguration in July 2017 when Nitish Kumar resigned and broke away from the Mahagathbandhan to form the government once again in alliance with the BJP. In alliance with JD (U) and LJP in the 2019 Lok Sabha election, the BJP alone won all 17 out of the 17 seats it contested with a vote share of 24 per cent. For the 2020 Assembly election too, it is in alliance with JD (U) and LJP and facing the RJD-led Mahagathbandhan that includes Congress and the three left parties (CPI, CPI-M and CPI-ML Liberation).

2020 election: NDA’s slippery ground versus Mahagathbandhan

Caste and community configurations and the alliance with JD (U) have been crucial for the growth of BJP in Bihar. With successive victories in 2014 and 2019 Lok Sabha election, the party has ensured that it is the equal partner in its alliance with JD (U) in the run up to the 2020 election. However, an official alliance with JD (U) and an ‘understanding’ with LJP (which walked out of the NDA over differences with Nitish Kumar) suggest that the BJP is keeping all options open and is making attempts to become the dominant player in state politics. The 2020 Assembly election will tell us if the BJP succeeds in its attempts or its ambitions are halted by the Mahagathbandhan like the 2015 election.

Notwithstanding the results, it appears that the JD (U)-BJP’s NDA will not find the going easy in this election over Chief Minister Nitish Kumar facing anti-incumbency after 15 years, particularly over lack of employment generation, the state government’s tardy response during the initial phase of lockdown- when workers from the state were stuck in different cities across the country and had to travel back in extreme conditions, shoddy quarantine facilities, agrarian and economic distress arising from the lockdown, the massive floods in August-September amid the pandemic, and so on.

The author is Independent researcher based in New Delhi

References

Ananth, V. Krishna. 2005. ‘Dawn of New Caste Battles? Economic and Political Weekly, 40 (49): 5142-5144

Chhibber, Pradeep. 1997. ‘Who Voted for the Bharatiya Janata Party?’, British Journal of Political Science, 27 (4): 631-639 (available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/194232)

Chowdhury, Neerja. 2015. ‘Bihar Polls 2015: A star caste bloc bluster’, The Economic Times, October 12 (available at https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/blogs/et-commentary/bihar-polls-2015-a-star-caste-bloc-buster/)

Hansen, Thomas Blom and Christophe Jaffrelot. 1998 (ed.). The BJP and the Compulsion of Politics in India. Delhi: Oxford University Press

Hauser, Walter. 1997. ‘General Elections 1996 in Bihar: Politics, Administrative Atrophy and Anarchy’, Economic and Political Weekly, 32 (41): 2599-2607

Heath, Oliver. 1999. ‘Anatomy of BJP’s Rise to Power: Social, Regional and Political Expansion in 1990s’, Economic and Political Weekly, 34 (34/35): 2511-2517

Jaffrelot, Christophe. 2003. India’s Silent Revolution: The Rise of the Lower Castes in Indian Society. Delhi: Permanent Black

Jaffrelot, Christophe. 2005. ‘The BJP at the Centre: A Central and Centrist Party?’ in Christophe Jaffrelot (ed.), The Sangh Parivar: A Reader. New Delhi: Oxford University Press

Jaffrelot, Christophe. 2015. ‘The Class Element in the 2014 Indian Election and the BJP’s Success with Special Reference to the Hindi Belt’, Studies in Indian Politics, 3 (1): 19-38

Jha, Girdhar. 2010. ‘BJP pulls off a big surprise on Nitish wave’, India Today, November 25

(available at http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/bjp-pulls-off-a-big-surprise-on-nitish-wave/1/121106.html)

Kumar, Sanjay. 1999. ‘New Phase in Backward Caste Politics in Bihar: Janata Dal on the Decline’, Economic and Political Weekly, 34 (34/35): 2472-2480

Kumar, Sanjay. 2002. ‘New Phase in Backward Class Politics in Bihar, 1990-2000’, in Ghanshyam Shah (ed.), Caste and Democratic Politics in India. Delhi: Permanent Black

Kumar, Sanjay. 2004. ‘Janata Regionalized: Contrasting Bases of Electoral Support in Bihar and Orissa’, in Rob Jenkins (ed.), Regional Reflections: Comparing Politics Across India’s States. Delhi: Oxford University Press

Kumar, Sanjay. 2012. ‘Caste Dynamics and Politics of Development in Bihar: Reading through results of Assembly Election 2010’, Think India Quarterly, 15 (1): 99-125 (available at http://www.thinkindiaquarterly.org/Backend/ModuleFiles/Article/Attachments/SanjayKumarPage99125.pdf)

Kumar, Sanjay and Rakesh Ranjan. 2009. ‘Bihar: Development Matters’, Economic and Political Weekly, XLIV (39): 141-144

Mishra, Vandita. 2010. ‘The Bihar Glossary’, The Indian Express, October 17 (available at http://www.indianexpress.com/news/the-bihar-glossary/698527/0)

Prasad, Binoy S. 1997. ‘General Elections, 1996: Major Role of Caste and Social Factions in Bihar’, Economic and Political Weekly, 32 (47): 3021-3028

Robin, Cyril. 2004. ‘Bihar Elections: Laloo against Who?’, Economic and Political Weekly, 39 (51): 5361-5362

Robin, Cyril. 2009. ‘Bihar: The New Stronghold of OBC Politics’, in Christophe Jaffrelot and Sanjay Kumar (eds.), Rise of the Plebeians? The Changing Face of Indian Legislative Assemblies. New Delhi: Routledge

Shah, Amita. 2010. ‘Bihar model, not Hindutva, is BJP’s future’, The Economic Times, November 25 (available at http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2010-11-25/news/27580529_1_bjp-brass-bjp-leadership-bihar-model)

Sridharan, E. 2005. ‘Coalition strategies and the BJP’s expansion, 1989–2004’, Commonwealth & Comparative Politics, 43 (2): 194-221 (available at http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/14662040500151093)

Sridharan, E. 2014. ‘Class Voting in the 2014 Lok Sabha Elections: The Growing Size and Importance of the Middle Classes’, Economic and Political Weekly, 49 (39): 72-76

Tiwari, Ravish. 2010. ‘First time since 2002 riots, Muslims vote for BJP Plus’, Indian Express, November 25 (available at http://www.indianexpress.com/news/first-time-since-2002-riots-muslims-vote-for-bjp-plus/715678/0)

Yadav, Muneshwar. 2004. ‘Politics from Below’, Economic and Political Weekly, XXXIX (51): 5510-5513

Notes:

[1] Robin (2009) sees this in terms of increased number of OBC Member of Parliaments (MPs) from Bihar and a subsequent decline in the share of upper caste MPs from the state (p. 65). Jaffrelot (2000) saw this phenomenon at the level of both MPs and MLAs (p. 98). Jaffrelot (2003) calls this transfer of power from upper caste to OBC politicians in the Hindi heartland as the ‘silent revolution’.

[2] Janata Dal (Rashtriya Janata Dal from 1997) was in power in Bihar from 1990 to 2005.

[3] After coming to power in 2005, Nitish Kumar set up the Land Reforms Commission under the chairmanship of D. Bandhopadhyay, which submitted its report in 2008. The report recommended allotment of land to agricultural labourers and enacting a Bataidari Act to ensure the rights of tenants/sharecroppers. However, the state government did not implement the recommendations.