Balu Sunil Raj

Balu Sunil Raj

The recent comments by the Bollywood actress Sonam Kapoor on justifying her privilege through the prism of Karma raised a hue and cry on Twitter. While several of the Twitterati understandably took objection to this tweet, the tweet ended up getting more than 31 thousand likes, which is many times more than the likes received by a normal tweet by Sonam Kapoor. This is probably due to the engagement with the tweet by many due to its polarizing impact. The fact that this was tweeted in the context of the nepotism debate in Bollywood, following the tragic suicide of Sushant Singh Rajput, makes it horrifically insensitive.

This incident is yet another reminder of the continuing hold which the concept of Karma has on the Indian Hindu psyche, particularly among the socio-economic elite, who are easily able to obfuscate the caste-class structures which cultivate inequality by resorting to the Karma doctrine. There cannot be a better fit in this category than Sonam Kapoor, who comes from a privileged Bollywood family of the Khatri caste. If one places her tweet in the historical context, there is no element of surprise, since it’s precisely in such contexts that the Karma doctrine has relevance. In that sense, there is a historical continuity.

The doctrine of Karma in the texts

One of the earliest references to Karma theory is found in Chandoggya Upanishad. It comes out as part of a discussion between King Jaivali Prahana and Gautama, a young person. While discussing rebirth the king says that

“ Those who behave nicely here will, in general, find a nice womb, the womb of a Brahmin or the womb of a Kshatriya or the womb of a Vaishya. But those whose behaviour here is a stinking will, in general, find a stinking womb, the womb of a dog or the womb of a pig or the womb of an Untouchable.”

To sum up, your actions in the previous birth cast a shadow on your soul and determine your life in the next birth and by extension, the social system based on caste hierarchy. This text is more than two millennia old, but Sonam Kapoor’s tweet represents the spirit of this text in totality. This is the same spirit that is found in most of the later texts. While some texts provide leeway where Karma can be attained through paths of renunciation, or by giving gifts to Brahmins, stricter enforcement of Karma is the attitude of well-known texts such as the Manusmriti and Bhagavad Githa.

For instance, the Manu Smriti says,

“And whatever Karma the Lord yoked each creature to at first, that creature by itself engaged in that very Karma as he was created again and again. Harmful or harmless, gentle or cruel, right or wrong, truthful or lying—the Karma he gave to each creature in creation kept entering it by itself. Just as the seasons by themselves take on the distinctive signs of the seasons as they change, so embodied beings by themselves take on their Karmas, each his own.”

The Indologist Wendy Doniger has noted how this quote from the Manusmriti indicates a notion of circularity associated with Karma. The point being that you cannot change yourselves, and the only option is succumbing to Karma. The Manusmriti also explicates the functions of different classes based on Karma.

“For priests, he [the lord] ordained teaching and learning, sacrificing for themselves and sacrificing for others, giving and receiving. Protecting his subjects, giving, having sacrifices performed, studying, and remaining unaddicted to the sensory objects are, in summary, for a ruler. Protecting his livestock, giving, having sacrifices performed, studying, trading, lending money, and farming the land are for a commoner. The lord assigned only one activity to a servant: serving these [other] classes without resentment”

There are fewer statements that legitimize servility as the aforementioned one. Predictably, the text is valorized by Brahmanical organizations like the RSS. They would complain in the late 1940s that Manu’s laws were not incorporated by the Indian constitution. There is nothing “Bharatiya’ about the Indian constitution, Savarkar would claim since laws of Manusmriti were not part of it.

The Bhagavad Gita also has a similar understanding of Karma. This comes out prominently when Arjuna is in two minds about fighting the Kurukshetra war when he doubts the overall purpose of it. Krishna, his charioteer, then points at the Karma doctrine.

“It is better to do one’s own duty, though ineffectively, than to perform another’s duty as it should be done; it is better to die in following one’s own duty; dangerous is the duty of other men”

“Action (Karman) alone is your primary concern, not the consequences”

Therefore, Arjuna should carry out tasks that are inherent to a Kshatriya without thinking about the consequences, even if it means killing his kinsmen in a carnage. If one extends the argument, no caste group should think of doing anything beyond their Karma, whether they like it or not. The result is an irrational subservience and internalization of the caste hierarchy. It should be noted that alternative normative systems in ancient India, such as Buddhism, would not have upheld an understanding which valorizes the inherent nature of certain classes. It is precisely why Romila Thapar famously observed that “ Had the Buddha been the charioteer, the message would have been different”.

The Mahabharata also has a similar understanding of Karma as Chandoggya Upanishand. This is how sage Bharadwaj elaborates it in book 12.

“Actually, there is no difference between the classes; this whole universe is made of brahman. But when the creator emitted it long ago, actions/Karmas divided it into classes. Those Brahmins who were fond of enjoying pleasures, quick to anger and impetuous in their affections, abandoned their own dharma and became Kshatriyas, with red bodies. Those who took up herding cattle and engaged in plowing, and did not follow their own dharma, became yellow Vaishyas. And those who were greedy and fond of violence (himsa) and lies, living on all sorts of activities, fallen from purity, became black Shudras.”

The point being that Karma doctrine was an essential component of the ideological weaponry which was used to defend the caste system. However, one should not overlook the material roots of this ideology. Formulation of Karma doctrine coincided with the movement away from pastoral life in the Vedic era to the life of settlements-both urban and rural in the first millennium BC. The hierarchical class systems which developed, as a result, needed ideological justification for its reproduction. It is here that the role of Karma comes into the picture.

Therefore, it would be erroneous to see the Karma doctrine in isolation; insulated from the social formation it was part of. It was integral for the reproduction of this social formation defined by the hierarchy which came into being in this era. For the socio-economic elites of this system, the Karma doctrine was not only about purity-pollution, but also about depressed wages, lack of mobility of lower castes, and class exploitation. All these factors contributed to thwarting the resistance of the marginalized.

To sum up, the tweet of Sonam Kapoor is understandable if one places her caste-class location in a historical context. Karma has always helped the socio-economic elite to legitimize inequality of all types, and she is merely continuing on a historical path that has been carved out by innumerable texts and practices.

Resistance and Contemporary Relevance

Despite the deep roots of the Karma doctrine in Indian society, it has met with resistance. Charavakas, the ancient Indian atheists didn’t abide by the notion of Karma. Later, the non-Brahmin movement would take up this mantle. Ambedkar would call it a ‘heartless law’ which has been used to subjugate untouchables for centuries. The critique of Karma is an integral component of his treatise against Brahmanism. Even when he converts to Buddhism, he reinterprets Buddhism by dispelling the notion of Karma and rebirth from it. He further points out that since Buddhism does not believe in the concept of a soul, it is incompatible with the Karma doctrine.

Further in the material realm, there have been contestations, even in medieval and ancient India. Indian sociology is filled with ethnographic findings which contradict the theory that caste hierarchy is internalized by lower castes. This goes directly against certain fundamentals of the Karma doctrine. Most sociological studies on caste point towards the power relations in explaining the subjugation of lower castes, rather than on the Karma doctrine.

However, despite all this, like a shadow, Karma continues to follow the Indian psyche, not ready to disappear. For instance, certain studies have noted that, as an ideology, Karma continues to play a role in the everyday lives of people. However, rather than the past life, it is mostly offenses from the present life which are used to explain one’s circumstances. Despite differences from the textual interpretations, these issues point to the continuing presence of Karma in our belief structure.

For the ruling classes of India and other property-owning class segments affiliated to them, and for the state which caters towards their interests, resorting towards the Karma doctrine as Sonam Kapoor did, helps in legitimizing massive forms of inequality created by capitalist development. It is a toxic mix of regressive traditions carried over centuries, coupled with capitalist ideology, which allows for the perpetuation of the ideological hegemony and domination by the Indian ruling class.

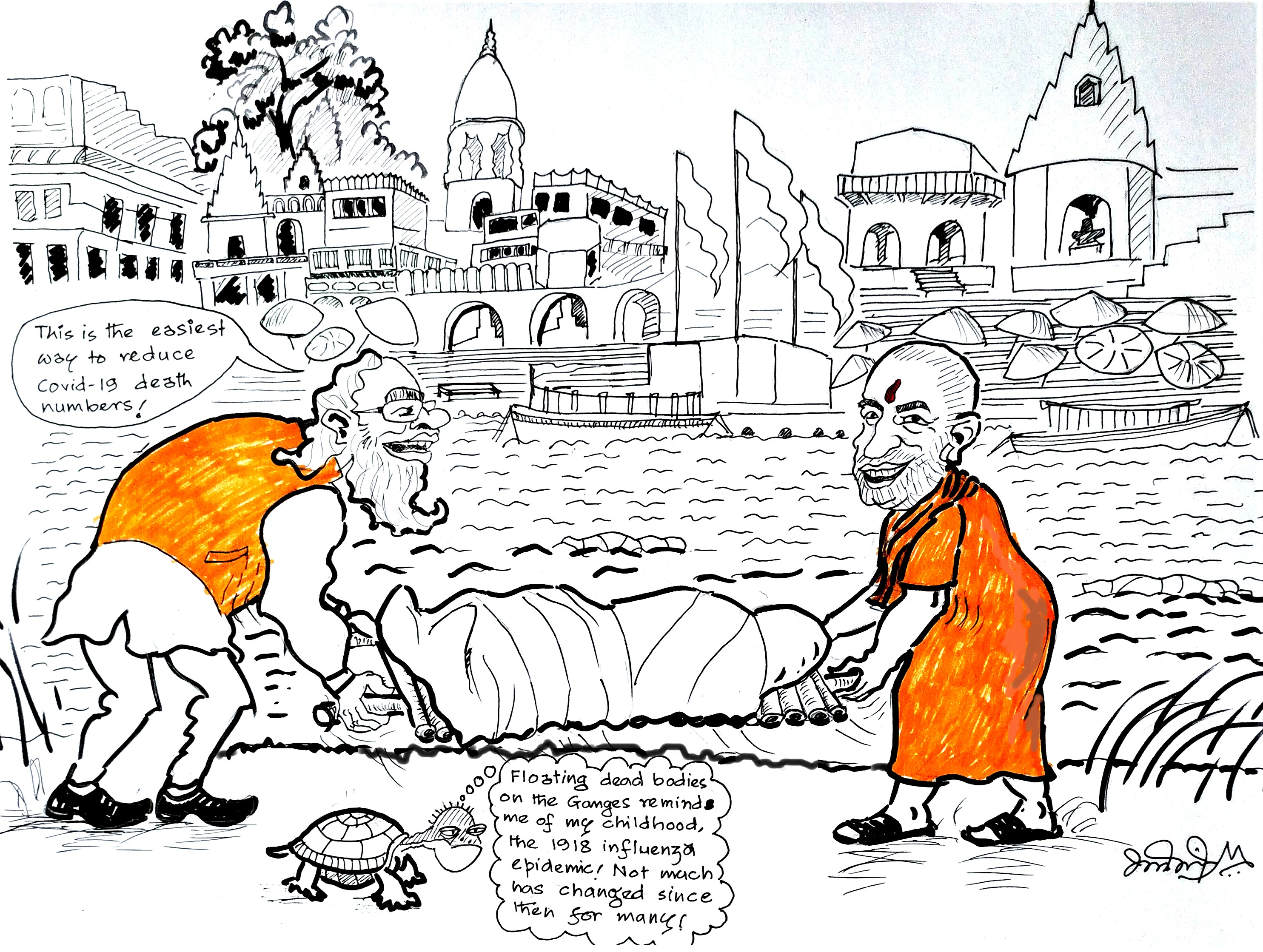

Under the BJP, this has become particularly evident, especially regarding governance. In many of their flagship schemes which result in widespread suffering, political salvage has been possible to an extent, by relying on principles of sacrifice and atonement; ideas which are associated with the notion of Karma.

In recent times, this was most evident during the lockdown episode. The state was able to divert attention from the misery it caused to millions of people by resorting to ideas about sacrifice and atonement. The atonement which the entire society had to bear, in resisting the COVID. However, similar to the impact of the Karma doctrine, it was the most vulnerable who suffered the most in the collective display of sacrifice and atonement. I wonder why the poor did not resist as they should have, even when they were forced to walk hundreds of kilometers, or when they died in Shramik trains which lost their way. Is it due to the deep-rooted influence of the Karma doctrine, celebrated by the likes of Sonam Kapoor?

Balu Sunil Raj is Senior Researcher, Centre for Equity Studies. He would like to thank Suchetana Chattopadhyay for her suggestions

(In her tweet, Sonam wrote, “Today on Father’s Day I’d like to say one more thing, yes I’m my father’s daughter and yes I am here because of him and yes I’m privileged. That’s not an insult, my father has worked very hard to give me all of this. And it is my karma where I’m born and to whom I’m born.)